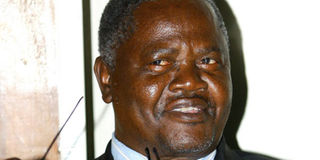

Remembering Prof Chris Wanjala

The late Prof Chris Wanjala. PHOTO| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- He had none of that haughty air that intellectuals sometimes surround themselves with.

- He listened to his students.

I met Prof Chris Wanjala 14 years ago as a literature student at the University of Nairobi’s Kikuyu campus.

There was nothing extraordinary about that meeting. I was the eager student and he was the distinguished lecturer.

But something struck me about his demeanour. There was something different about the way he interacted with us compared to other lecturers.

He had none of that haughty air that intellectuals sometimes surround themselves with. He listened to his students. He let us have our say and dismissed none of our arguments.

But more than that, he was unafraid of admitting when he did not know something.

I remember he once received a call while in class from a newspaper reporter, asking him about a subject he knew nothing about. He promised to call the reporter back and turned to us, admitting he knew nothing of the subject and asked us to give him direction. Which we did.

EXTRAORDINARY KNOWLEDGE

My appreciation for East African and South African literature grew and matured because of his extraordinary knowledge and lecturing style.

He would oftentimes speak of the writers as one would an old and trusted friend -- as if he knew each of them personally. Alex La Guma, Es'kia Mphahlele, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, JM Coetzee, Nadine Gordimer and David Rubadiri were constant visitors in our class because of Prof Wanjala and he would make us fall in love with the personalities of the writers long before we even read their books.

And indeed, he had interacted with some of them.

He recounted to us tales of meeting Mphahlele in the 1970s when the latter lived in Kenya.

But as flexible and accommodating as he was as a lecturer, he was equally unwilling to compromise on our learning and suffered no fools, as he demonstrated once when he lost his cool.

It was during a literature examination and one of us had not only snuck in a Mwakenya (little scraps of paper with possible exam answers) but also had the audacity to refuse to reveal her admission number when he asked for it so that he could take the necessary disciplinary measures.

“Doctor, please sir!” she pleaded with him, imploring upon him not to take any measures against her, to which he answered explosively:

“I am NOT a doctor!”

Of course, he was not a doctor, and the poor girl was simply clutching at straws, hoping to placate him somewhat by referring to him as a doctor. We watched in horror as she pleaded and as he told her exactly why she would not be graduating.

Upon learning about his death, one of his former students wrote this in our alumni group:

“He was a great teacher. But I’ll always remember he remarked on my hard-worked term paper in First Year that it was not university quality. That stung!”

Needless to say, we knew never to mess with him.

He would often tell us about opportunities and would ask some of us students to accompany him for literary radio programmes and encourage us to share our knowledge as well.

FATHERLY ADVICE

I graduated from university eventually but continued interacting with Mwalimu, as I often called him, in various literary circles, with the most recent being PEN-Kenya, where we both served as officials.

He laughed easily, something I found quite endearing and when we interacted with high school boys during a visit by PEN-Kenya to St Peter’s Mumias Boys High School, he regaled us with tales of his boyhood. And later, while sitting around a fire in the evening, he reflected upon what it meant to be a father, especially a father of boys.

“Fathers need to know that their presence matters. Be there. Just be there for your children,” he concluded.

Mwalimu will be remembered for many things, chief among them his contribution to Kenya’s literary history.

I will also remember him for shaping not just my experience of literature but also my view of the world.