In impressive KCSE results, a reason to smile and to worry

What you need to know:

- Machakos Girls’ High School principal Florah Mulatya has said the school’s performance, which saw 49 students score A grades (A or A-) in KCSE this year, was the best since the institution was established 100 years ago.

- That performance may pale in comparison to Moi Kabarak’s with its mouthwatering 248 As, or Alliance High’s with another eyeball-popping 248, or Maranda High’s with its jaw-dropping 265 in the 2014 KCSE exam, but still it shows a student population that is keen to pile on the points and break records.

- The species, it seems, is getting sharper by the day. Or is it?

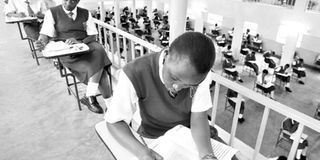

If the recent results of the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education are anything to go by, the average Kenyan student is getting more and more intelligent.

If you doubt that, consider that a whopping 14,841 students scored A grades (A or A-) as their mean scores, compared to 12,481 students a year earlier.

Consider, also, that this year, for the first time in the history of Kenyan examinations, Mandera County produced an A student, in the name of Ibrahim Abdi Ali of Sheikh Ali Secondary School, who scored an A.

An A, as many who went through the education system about 15 to 20 years ago will tell you, was a hard thing to come by in the past, almost a preserve of the best schools in the country and a chest-thumping point for such giants as Alliance High School and Starehe Boys’ Centre.

Today, however, the significance and supremacy of this grade has been watered down by the numbers. It is too easy to score an A or A-, it seems. Too easy and too commonplace.

Take, for instance, Mukaa Boys’ High School in Makueni County. You probably have never heard of this school, but you need to; because Mukaa Boys’ High School had a total of 36 students scoring A grades as mean scores in the 2014 KCSE, with four of them scoring A plains.

Mukaa Boys’, which posted an impressive mean score of 9.08, was second in Makueni County, after Precious Blood Kilungu (mean score 9.5). It beat a couple of national schools — like the nearby Makueni Boys’, which posted a mean score of 9.00.

Machakos Girls’ High School, which led in Machakos County with a mean score of 9.45, had 49 students scoring A grades as overall mean scores, with seven of them registering A plains.

The girls beat their perennial rivals Machakos School, which had five boys scoring the top grade of A plain.

A game of chance? No, we don’t think so, especially not after Machakos Girls’ principal Florah Mulatya said the performance of her girls was the best since the school was established 100 years ago. In 2013 the school had a mean score of 8.8.

Mukaa Boys’ and Machakos Girls’ performance may pale in comparison to Moi Kabarak’s, with its mouthwatering 248 As, or Alliance High’s with another eyeball-popping 248 As, or Maranda High’s with its jaw-dropping 265 As in the 2014 KCSE exam, but still it shows a student population that is keen to pile on the points and break records. The species, it seems, is getting sharper by the day.

Or is it?

While releasing the 2014 KCSE results, Education Cabinet Secretary Jacob Kaimenyi said the performance was the best in three years. A total of 149,717 students (a mere 283 short of 150,000) qualified to join university after attaining grade C+ and above. This is double the available university slots since last year only 72,000 were admitted into Kenyan universities.

The students who received their results this year are the first lot to go through the entire system of the Free Primary Education programme introduced by the Kibaki government in 2003.

Questions have been raised over the quality of education and instruction in public schools as a result of the high pupil-teacher ratio, but the results tell a different story.

On the question of schools posting more A grades, a Nairobi-based teacher who asked to remain anonymous said the trick lies in finishing the syllabus early so as to have ample time for revision.

He revealed that by end of this month teachers in his school will have completed the syllabus and hence embark on thorough revision for the remaining part of the year.

“It’s not a new thing,” he said. “We have been posting a mean score of 10 and above every year. We take our students through science practicals every day so that when the exam comes, there is nothing new,” said the teacher.

Many other schools from different parts of the country have been visiting the school to “benchmark”, he said, adding that this could have contributed to more students elsewhere scoring A grades as the teachers may have implemented what they observed at the school.

“Right now we are hosting a team from a school in the coast which has come to benchmark for one week. If they put into practice what they have learnt, they will excel,” he said.

Form One selection also contributes to good performance. National schools usually take the top cream of pupils in the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education exam, and when this high-grade breed is weaned on the tradition of excellence that must be maintained in some schools, a spanking A does not sound like such a foreign, up-there-in-the-sky concept anymore.

Mukaa Boys’ principal Francis Mutua, however, does not think today’s students are any sharper than those of, say, 20 years ago. It is the teaching that has gone hi-tech, he says.

“Today we have e-learning programmes and some teachers use projectors to teach science subjects. The student is able to see the object in three dimensions,” says Mr Mutua.

He says chemicals used for practicals are also now quite affordable and students can undertake as many lessons as possible. The science laboratories of many schools have also improved as opposed to the past when many schools had to do with make-shift structures.

Mr Mutua has another very interesting opinion on why the current crop of students is performing exceptionally well.

“Today’s students come from middle-class backgrounds that know the value of education. Their parents invest a lot in education and they are therefore under pressure to perform,” he observes.

Besides that, schools are now investing in revision material and motivational speakers, he says. This enables students to be highly motivated as experts in various fields are brought to the schools to talk to the students.

But another teacher from a well-performing boys’ school in Machakos County has a different take on this good performance.

“Don’t be fooled,” she cautions. “The students are no brighter than we were. These days it’s just easier to get leakage of the exams. Some principals even pay to have their students awarded top grades.”

Her hypothesis may not be far-fetched, given that a top official of the Kenya National Examination Council has been mentioned in the infamous Chicken Scandal in which Kenyan elections and examination officials are accused of receiving bribes in order to award printing contracts to a UK-based company, Smith & Ouzman.

That hypothesis also raises questions why, despite the fact that every year schools are penalised and their results cancelled for alleged cheating, no official of the examinations body has been charged for leaking the exams.

Since 2000, KCSE students have been posting quite impressive results, forcing university admission boards to adjust their entry cut-off points upwards. Competition among schools has also been high, forcing the government to ban the ranking of schools in a bid to cool down the performance engines.

In banning ranking, the government also cited unethical competition practices, essentially advancing the argument that while trying to get ahead of everyone, schools were ruining education in Kenya.

According to the government, even though there were various other reasons why ranking had to be done away with, the most important was the need to eradicate cheating in exams as schools sought to post good grades and be ranked high. It did not matter how the schools achieved the results; the end justified the means.

Prof Kaimenyi, while announcing the ban on ranking, said some schools were better equipped than others and therefore it did not make sense to rank students who did not have the same facilities or opportunities.

“Why torture the students of ill-equipped schools by ranking them against better-equipped schools and exposing them as failures?” he posed.

Prof Kaimenyi said the practice stigmatised students who performed poorly, but critics have argued that ranking is an educational tool that encourages competition.

The good results posted in recent times are despite an outcry from independent organisations like Uwezo Kenya on the declining quality of education in the country.

Uwezo, a non-governmental organisation that monitors education trends in Kenya, has in the recent past released damning reports on the quality of education in the country since the introduction of free primary education.

In one of its reports, released in 2010, the organisation observed that one out of every 10 Standard Eight pupils could not even tackle a Standard Two mathematical problem.

The assessment covered 2,030 public primary schools, with researchers interviewing pupils from 40,386 households from 70 districts.

The research found out that 30 per cent of Standard Five pupils would fail a Standard Two mathematical problem while 20 per cent of Standard Two pupils would be able to solve it.

A third of children in Standard Two could only recognise numbers but could not perform basic calculations on the same, according to the report.

It further observed that for every 1,000 pupils in Standard Eight, 50 could not read a story meant for Standard Two. Also, only a third of children in Standard Two could read a paragraph set for their level.

“Our children are not able to do what they should be doing at their level in terms of numeracy and literacy,” said Mr Daniel Wesonga, a lecturer at Kenyatta University who was part of the team that carried out the research. “The situation is grim.”

The study reported many children in primary school, including those in upper classes, could not read, write or perform numerical calculations meant for their level.

“These low performances may be affecting performance at higher levels and inability to read could be a problem to even students in secondary schools,” the report said.

One wonders how pupils who were the subject of the research, and who have now gone on to sit their KCSE exams, managed to post some of the best ever results in the history of the country’s schooling. As people are wont to ask when things do not make sense, who is fooling whom?

Dr John Mugo, the Uwezo Regional Manager, says their report is still correct given that 35 per cent of those who sat their KCPE exams in 2010 did not transit to secondary school.

Although he admits that the transition rate has now increased to 75 per cent, he explains that there are still a lot of students who score E grades in KCSE, and that those could be the ones his report captured.

On students scoring A grades, he says teachers have devised ways of preparing students for exam.

“It’s not possible that students are getting brighter; teachers have just devised ways of teaching for exams. In forms Three and Four anything that is not examinable is no longer taught,” he says. “It is not clear how this is impacting on acquisition of knowledge yet we are supposed to produce well-rounded persons.”

He adds that, although the content has not changed, the number of subjects is fewer compared to the 1990s, allowing students to have enough time to study and excel.

So it could be that, even as students post better results, they are not necessarily any sharper than generations before them. The syllabus is lighter, teachers are working harder, and anything that is not examinable does not bother instructors.

In the end, performance triumphs over all-rounded intelligence. Which is why, as one person put it, you have A students who struggle to fit within the dynamic world of employment.

In a system that rewards academic regurgitation rather than critical thinking, it is not that hard to come across a doctorate fellow who cannot string a coherent sentence.