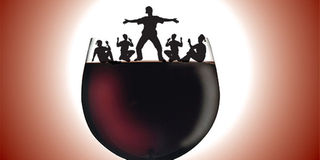

Why alcohol makes you feel like the greatest man who ever lived

What you need to know:

- Feeling high as a kite? That is because the booze you have just imbibed has increased the release of the dopamine hormone in you brain’s ‘reward centre’, flooding you with a feel-good effect. The reward centre is the area affected by all pleasurable activities, including hanging out with friends, going on vacation, ingesting drugs, or getting a big bonus at work

On a fine Friday evening last month, three men walked into the swanky Club Natives on Thika Road, ready to have the best night of their lives. It was around 9.30pm and Fredrick Lusina, accompanied by two of his cousins, was all set for a beerfest.

The club was fully packed, but they still managed to secure a place. “Leta kama tulivyo” (serve everyone), Lusina recalls instructing a waitress. “It’s going to be a long night.”

As it always happens during drinking sprees, after Lusina ordered the first course of Famous Grouse to set the mood, one of his cousins then called the waiter and asked for Pilsner Ice for everyone. This was their second course.

“Within a few minutes I had made new friends.... beauties, of course,” says Lusina, flashing a sheepish smile. Shortly afterwards, he espied a high school friend and popular Nairobi comedian making a grand entry into the club.

Heads turned as the man made the few steps to his table, but Lusina, now slightly inebriated, would not be bothered. He would talk to his friend once the commotion around him had died down, he reasoned.

Lusina says he and the comedian were drama club members in high school and that they were always best friends. Fate, however, had charted different courses for them — one leading Lusina to university, the other sending his bosom friend to comedy.

Their friendship had been dealt a blow and now, sitting on a bar stool at Club Natives, the two had met after years of separation.

What Lusina did not know, however, was that his friend had made new acquaintances and that their days in high school were well behind him. That biting reality occurred to him as soon as he walked to his friend’s table.

The comedian remembered him alright, but he did not rise to meet Lusina’s enthusiastic approach. Instead, he gave him a casual glance and a feeble “hi”. This lit a fire inside Lusina’s belly.

“Though we hardly met after high school, I never stopped considering him a friend,” he told DN2.

“Every time we bumped into each other I would try to talk to him, but he would ignore me.” He said he had always excused his friend, reasoning that he was probably a busy man who met many people and that his memories about him may have been lost in the maze of time. He said he forgot about it “as I never thought we would cross paths any time soon”.

Given him some courage

And then, out of sheer coincidence, they had bumped into each other, this time in a club, with Lusina high as a kite. The alcohol had given Lusina some courage and so he confronted his high school friend.

A war of words ensued during which Lusina accused his friend of pretending he did not know him now that he had found fame, and maybe fortune as well.

We could say that Lusina was envious of his friend’s relative success and was simply playing the vendetta card or that his friend was guilty as accused.

Whatever the case, the alcohol coursing through Lusina’s veins was responsible for his straightforward, confrontational, and “truthful” approach. If he had not been drunk, he probably would have retreated once his friend met his enthusiastic approach with biting casualness.

This raises a number of questions about the effect of alcohol on one’s mental state and how that translates to irrational boldness. Is it true, for instance, that only a drunk person — or a naive child — can tell you the truth?

We ask this because cases of conservative people talking too much after imbibing or young men hitting the bottle to get the courage to approach girls are commonplace.

Mr Job Kithinji, a psychologist and consultant with the National Authority for Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (Nacada), says alcohol is used by some to gain courage.

This, says Mr Kithinji, is called disinhibition, “whereby one’s socialising problems that manifest when sober are blurred and thus one is able to do things one may not do when free from alcohol”.

Disinhibition also affects social controls, such as consciousness of what is bad and good and ability to avoid risky social behaviour. It is a result of alcohol’s interference with normal brain functioning and so, due to this, “one is unconscious of what he or she is engaging in,” says Mr Kithinji.

“In normal circumstances, it’s impossible that one would engage in risky social behaviour such as being abusive, relieving oneself in public, or engaging in clumsy fights,” he explains.

However, when drunk, disinhibition affects the limbic system — which is located right under the cerebrum and supports a variety of functions, including emotions, behaviour, motivation, and long-term memory — altering information flow, which leads to saying or doing things that one would not do when sober.

“The electrical signals between synapses — the points at which a nervous impulse carrying senses, data, and information in the body pass from one neuron to another — are interrupted, cutting the nervous impulse flow and resulting in mood swings and exaggerated states.”

The cause of bar fights

This, explains Mr Kithinji, includes misunderstanding somebody’s intentions, which is the cause of most bar fights, amplifying your own feelings, which is the cause of most bar breakups between friends or lovers, or simply saying something regrettable or embarrassing, the cause of most Sunday morning face-palms.

According to How Alcoholism Works, a research paper by Stephanie Watson, disinhibition is as a result of alcohol’s effect on the cerebral cortex, the region in the brain where thought processing and consciousness are centred. Alcohol, says Ms Watson, depresses the behavioural inhibitory centres, making an individual disinhibited.

As a result, “processing of information from the eyes, ears, mouth, and other senses is slowed, inhibiting the thought processes and thus making it difficult to think clearly”.

This, explains Ms Fatuma Musau, programme director at CareTech Medical Centre in Kiambu, is known as distortion.

“The body functioning is altered in a way that one lacks boundaries,” she says, adding that, due to alcohol’s effect on the cerebral cortex, a patron at first instance will see the barmaid looking awful, but after hitting the bottle, the barmaid starts to progressively grow beautiful.

On the other hand, Mr Kithinji chips in, alcohol increases the release of the dopamine hormone in the brain’s “reward centre”, flooding one with a feel-good effect. The reward centre is the area affected by all pleasurable activities, including hanging out with friends, going on vacation, ingesting drugs, or getting a big bonus at work.

“By releasing the dopamine hormone, alcohol tricks the patron into thinking that he or she is actually feeling good in case one is drinking to get over something emotionally difficult,” says Mr Kithinji.

However, the effect is that one keeps drinking to get more dopamine release while at the same time altering other brain chemicals that may enhance feelings of depression.

How alcohol affects the brain — and indeed the rest of the body — is different among genders. The effect of dopamine, for instance, is more significant in men than in women, which explains why men drink more than women on average.

“Still, there are many other factors at play, not only in women, but across different personalities,” notes Ms Musau, adding that some people will, for instance, drink more than others owing to their genetic make-up, mental state (stressed people tend to get inebriated faster), and whether the individual is drinking on an empty stomach.

According to results from the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, alcoholism affects more men than women in Kenya. About 10 per cent of men, compared to between three and five per cent of women, become alcoholics over the course of their lives.

Ms Salome Nthenya, a Tusker ambassador, says she has never understood why people become rowdy when they take alcohol.

“People who look conservative start talking a lot after a couple of drinks,” she says.

Fake bravado

Mr Kithinji explains that the bravado is actually false. “Alcohol consumption leads to the release of empty calories that produce energy,” he says. “This is the reason people talk a lot.”

Disinhibition is part and parcel of this since a person’s social controls are lowered by alcohol intake, he adds.

For the shy, alcohol acts as a social lubricant, making interaction easier, while for those who go quiet after getting inebriated, alcohol becomes a central nervous system depressant. Others become forgetful, a sign that alcohol has affected the metabolism of vitamin B in their body.

“Vitamin B is responsible for our good brains,” says Ms Musau, “and, depending on a person’s genetic make-up, the effects will be diverse, ranging from extreme forgetfulness to one that lasts just a few minutes.”

A few weeks ago, Sunday Nation columnist Carol Njung’e wrote about how a friend once told her how her (friend’s) husband called her and told her he had Sh1 million. He promised to be home in 30 minutes so that they could plan how to spend it.

It turned out, though, that the man had been in a pub imbibing and that his dopamine hormones had been stroked, giving him an exaggerated feel-good state. He reached home early the following morning, minus the Sh1 million and he could not even remember calling his wife the night before.

To paraphrase a Russian saying, what a sober man has in his mind, the drunk one has on his tongue.

Fr Wilfred Mwaura of St Teresa’s Catholic parish in Eastleigh does not understand why it should take alcohol for a person to tell the truth.

That presupposes that an individual has something against another and is just using alcohol as scapegoat, he argues.

“The church teaches good morals and the art of honesty, but when it comes to walking the talk, that entirely lies on an individual,” says the priest.