How fortunes have changed for Loliondo’s Babu

What you need to know:

- Last year, Mr Masapila pulled hundreds of thousands of people into the Loliondo area by dispensing a herbal concoction purported to cure HIV/Aids, cancer, diabetes, epilepsy, asthma and hypertension and any other ailment

- April 2011 was a special period in Loliondo. Airtel and Vodacom rushed in to erect masts to tap into the huge market of an estimated 20,000 people who poured every week to seek Masapila’s alleged miracle cure

- Mr Masapila’s vehicles are additional assets that have improved the villagers’ lives as they have been deployed during “emergencies” during the day or night

- In terms of income – and he asked us not to place much value on it – the man is said to be collecting a paltry TSh25,000 (KSh1,300) from an average of 50 patients who stop by every week. He still dispenses the cup of the concoction at TSh500 (KSh27), which is shared with his aides and some saved for his planned centre

- At the height of his fame, Mr Masapila was said to have been pocketing a minimum of TSh5 million (KSh267,000) every day worked

At Samunge village in rural northern Tanzania, one would not fail to notice young Maasai men flaunting mobile phones fastened to their beaded waist bands.

Until recently, Samunge residents knew nothing about mobile phones but now the mobile phone is the craze among the villagers. They use the gadgets to make and receive calls, play music or listen to the radio as they go about their daily chores.

The mention of Samunge conjures up images of the self-declared prophet Ambilikile Masapila or Babu wa Loliondo, who captured the world’s attention last year with the so-called “wonder drug”.

And, thanks to Mr Masapila, the typical Maasai hamlet of Samunge, which is nearly 500 km north of Arusha town, is enjoying technology and connectivity to the outside world. Because Babu, as those who flocked to his humble home called him, brought the world to Loliondo.

In response to the need created by the influx of visitors to the remote village, mobile telephony companies Airtel and Vodacom erected masts in the village to tap into the new market. And so the villagers acquired cell phones.

Today, the long queues of vehicles and patients with all manner of ailments waiting for their turn to take a cup of the “wonder drug” are gone.

Mr Masapila’s home is quiet, with only a trickle of visitors coming in daily. The helicopters are no longer hovering overhead. The hustle and bustle is simply gone and in its place a serenity only disturbed by the occasional arrival of guests and the construction of new permanent houses in the neighbourhood.

Down the rough road, as one approaches the scattered structures that make the local market, scores of women wait outside one of the buildings to grind maize meal. But on this day, they are unlucky as the newly installed posho mill – by Mr Masapila – has broken down.

At the market, a young man has opened a kiosk and installed a small solar panel that he uses for lighting and charging the new mobile phones at a fee.

And at a nearby site, masons are busy building a guest house, one of the structures that have added to the changing face of Samunge. When completed, it will be the only lodge in the vicinity.

Elsewhere, and despite the fact that the area is inhabited by the Maasai and their Sonjo cousins, who are pastoralists and like living in manyattas, some are assuming a modern lifestyle. Permanent houses are sprouting all over the landscape.

Roads graded

Nyundo Senaya, 32, a resident of Samunge, says it is no longer the same village it used to be a few months ago.

“We have (mobile) network coverage and our roads, as you can see, are being graded. Communication has been simplified and transport, while not satisfactory, is not as problematic,” he says.

Mr Jackson Dudui credits the opening up of the area to the retired Lutheran Church of Tanzania pastor, 76-year-old Masapila.

Last year, Mr Masapila pulled hundreds of thousands of people into the Loliondo area by dispensing a herbal concoction purported to cure HIV/Aids, cancer, diabetes, epilepsy, asthma and hypertension and any other ailment.

Though it was never scientifically proved that it did cure any disease, Loliondo exploded into a frenzy of activity with visitors arriving from all over East Africa and beyond.

April 2011 was a special period in Loliondo. Airtel and Vodacom rushed in to erect masts to tap into the huge market of an estimated 20,000 people who poured every week to seek Masapila’s alleged miracle cure.

The network covers only a radius of about 10km from Samunge. The nearest other point with mobile network coverage is Loliondo township, 50km away.

When Lifestyle visited Mr Masapila last week, we witnessed the changes that have taken place in his own life.

Mr Masapila is no longer the frail old man with a shaky voice. He has grown somewhat stocky with a firm presence despite his age.

He talked to us outside his newly constructed three-bedroom self-contained house.

Although the humble one-room mud-wall hut that used to be his house still stands in its place, the homestead has undergone a complete transformation.

It boasts of, among other things, a brick house with a galvanised sheet roof, a Euro satellite dish he uses to receive television signals and a solar panel for lighting and powering his radio and TV. There is piped water too.

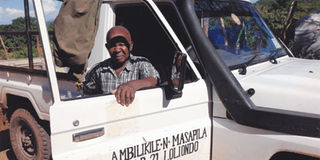

Parked in the compound was a 14-tonne lorry and a four-wheel-drive Toyota Land Cruiser truck – proof of the retired pastor’s rising status.

He says that he spent over TSh60 million (KSh3.2m) on the Land Cruiser and TSh14 million (KSh747,000) on the lorry. He also co-owns the lone posho mill that has saved women the cost of seeking a similar service far away.

He has employed some 31 young men and women whom he pays an average of Tsh150,000 every month. Most of them help him in preparing the herbs which he continues to dispense to the few people who occasionally come knocking on his door.

The employees also work at a nearby 20-acre plot where, Mr Masapila says, he intends to establish a pastoral and treating centre he describes as a “world-wide mission to minister to the sick”.

“It is a mission that I saw in one of the many conversations I had with God in my dreams,” he told Lifestyle.

It is rumoured that Mr Masapila saved more than TSh250 million (KSh13.3 million), money raised from those who sought his “medicine”, for the planned facility, even though he prefers to keep secret matters of finance.

Masapila’s vehicles

Marko Nedula, Peter Kanangira and Thobias John, who worked closely with Mr Masapila, are said to be among those who have built new brick houses that dot the village. We counted six of them that are at different stages of construction.

Mr Masapila’s vehicles are additional assets that have improved the villagers’ lives as they have been deployed during “emergencies” during the day or night.

Other than the changing face of the village, Mr Masapila’s mission has taken a blow with the number of patients having plummeted to near zero. He spoke candidly about the challenges that came with his work and fame. He said he was soldiering on despite critics whom he lamented “soiled my name by labelling my work a sham”.

Mr Masapila himself is alive to how his fortunes have changed. The long vehicular queues, reputed at one time to have stretched for 50 kilometres, have long disappeared, as is the sea of humanity that characterised the early days of his highly publicised “mission”.

The green foliage along the road leading to his homestead is abundant, contrasting greatly with the trampled bushes and temporary camps that littered the village.

Ask for direction

It is not entirely surprising that the occasional visitors have to ask for direction to Mr Masapila’s homestead.

In terms of income – and he asked us not to place much value on it – the man is said to be collecting a paltry TSh25,000 (KSh1,300) from an average of 50 patients who stop by every week. He still dispenses the cup of the concoction at TSh500 (KSh27), which is shared with his aides and some saved for his planned centre.

At the height of his fame, Mr Masapila was said to have been pocketing a minimum of TSh5 million (KSh267,000) every day worked.

“The money is not my focus or concern, as this is God’s work to which you cannot place financial value,” he says.

He says his work or success should not be measured by the size of the crowds that want to drink the concoction.

“There are several reasons why you don’t see many people, unlike before, but I cannot abandon God’s mission,” he says.

He says a majority of Tanzanians, Kenyans and Ugandans have stopped going there because they have already taken his medicine.

“Kenyan drivers are now only bringing South Sudan nationals who are just learning about my healing,” he says.

He claims that propaganda and smear campaigns waged by medical doctors and NGOs and witch-hunt by pentecostal churches instill fear in would-be “pilgrims”.

“They are spreading falsehoods that I am dead or have escaped to an unknown place. Out of pure jealousy, some church leaders have branded me a con-man and liar out to fleece people of their money.”

“But I know their main worry was that the doctors were losing patients who were deserting their facilities in droves and the churches their faithful, who believed in this mission,” he says.

He points an accusing finger at a maverick evangelist in Dar es Salaam who called him “a prophet of doom”.

“I am proud of my mission that saved thousands. Those fighting me should know they are fighting a losing battle because it is not me they are facing, but God himself and He will punish them.”

Mr Masapila says God did not like the kind of suffering his people underwent just to reach his “anointed prophet”.

“It is a sign he was angry at those who took advantage to profiteer from those who wanted to come here. Exorbitant fees, long queues and cold nights brought more suffering that will end with the coming of the new mission centre,” he says.

In defence of reports that some of the patients he gave the herbs did not get cured or they ended up dying, Mr Masapila insists this is part of the propaganda against him.

“My work is the work of faith and faith cures only those who believe in God and follow his word.

Mine is, therefore, just to dispense the medicine and God heals,” he says, citing the case of his own son who died of malaria.

A woman who had taken his concoction seeking a cure for diabetes and did not get cured posed the question to him as to why she did not get cured.

After seconds of awkward silence and after learning of the presence of journalists, the woman and her niece said to have cancer were ushered into the house for “further consultations”.

The duo was in a group of four staff of a Dar es Salaam-based NGO on a field trip. He told them it was a matter of faith.

Mr Masapila’s biographer, Atufigwege Mwakalinga, who has captured his life story in a 90-page booklet published last February, told Lifestyle from Arusha that the critics of the “Loliondo cure” were not well grounded in faith to comprehend what was going on.

“In researching for the biography I talked to people from Tanzania and Kenya who testify how this cure saved them. It is hypocrisy, therefore, for those throwing stones from the pulpit at a fellow man of God,” Mwakalinga said.

He said miracles could only come to those whose faith was unshakeable.