Joe Khamisi: Autobiography of a free slave descendant

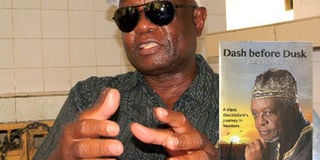

Joe Khamis and inset his memoirs, Dash before Dusk: A Slave Descendant’s Journey into Freedom. PHOTO | NATION

What you need to know:

- He writes: “Dash before Dusk: A Slave Descendant’s Journey into Freedom represents my life history of more than 65 years, spent in five foreign countries, three of them while in the service of the Kenyan government.

- It is a story of my humble beginnings in a slum town in Mombasa at the end of World War II and my journey as a journalist, diplomat and politician.”

- Lack of academic progress didn’t stop him from working as a journalist, tour company owner, a diplomat and a politician whose Bahari constituency was voted the best user of the Constituency Development Funds for all the years he was the MP.

Joe Khamisi seems to be one of the few Kenyans capable of speaking their minds. One would say that a politician’s son and a politician himself should naturally be expected to talk openly.

But there are tens of politicians – and other public personalities – who believe that their lives are private and should remain so, even when all their lives they have been paid by the public and declare all the time that they are “servants” of the people.

Well, Khamisi, once again tells a lot about himself, his family, his people and this country in his memoirs, Dash before Dusk: A Slave Descendant’s Journey into Freedom.

MULTIPLE ETHNICITY

The book picks up partly where The Politics of Betrayal: Diary of a Kenyan Legislator story ended. But in this new book, Khamisi spends less time on politics and more on his personal story.

In order not to say too much about the book, I quote his words in the preface and briefly tell you why I recommend it for your reading.

He writes: “Dash before Dusk: A Slave Descendant’s Journey into Freedom represents my life history of more than 65 years, spent in five foreign countries, three of them while in the service of the Kenyan government. It is a story of my humble beginnings in a slum town in Mombasa at the end of World War II and my journey as a journalist, diplomat and politician.”

He continues: “In this autobiography, you will read about my multiple ethnicity in a background anchored on the abominable slave trade, and about my agonising early upbringing in a single parent home.

“As a descendant of slavery, I have included a narration – at the back of the book – of the significant role my people played and continue to play, in the development of our adopted country, and the pain and struggle for recognition we continue to endure...”

The rest of this eloquently told story you’d have to find out for yourself. But I can speak about why Kenyans need to read and reflect on Khamisi’s autobiography. First, Khamisi tells us about the troubles that people like him – those generally described by officialdom and supposed natives as aliens – live through in this country. It is a tragedy that 50 years after independence we still think of some Kenyans as not original Kenyans.

So, there are thousands of Somalis who can’t get an identity card or passport because they can’t prove that they are autochthonous Kenyans; some Nubians are still told to go back to Sudan when looking for national documents.

Which Kenyan tribe or individual can prove that it or she is an original inhabitant of the place they call home today?

FOREIGN KENYANS

Why would people like Khamisi – simply because their parents were abducted in far away Malawi and Tanzania – who were born, grew up, studied, married, worked for the government, contributed to development of this country, remain socio-cultural “foreigners even if they are officially recognised as Kenyans? ”

Secondly, Khamisi’s story is interesting in the manner in which he makes a case about our kind of cosmopolitanism. Often Kenyans think that to be cosmopolitan you have to have travelled far and wide.

Not really. Cosmopolitanism is about taking the best of behaviours, thoughts and cultures from your people and neighbours and strangers you meet. But it is also about being open to new ideas and challenges.

Khamisi shows in his book how despite not being “local/Kenyan”, the freed slaves in the church-run mission station at Rabai where his grandparents first settled, the newcomers easily integrated locally.

Although he was later to be a victim of tribal alienation in the 2007 elections, as he alleges, Khamisi only feels disappointed at the betrayal by his people and the electoral process; but he is not angry.

Khamisi’s lineage contains grandparents from Tanganyika and great-grandparents from the Nyanja people, (related to the Chewa) today found in Malawi, and a Taita grandparent. He is a child of the world, rather than just Kenya. It is no surprise that his wife is American.

Such women and men are in short supply in today’s world, where even those who claim to have travelled, sampled and absorbed others’ cultures, remain jingoistic. Probably, one needs the kind of ancestral worldliness of Khamisi to have a heart like his.

Thirdly, the simplicity of this story is fascinating. In a true journalistic style, you won’t run looking for a dictionary to check the meaning of a word in this book. The anecdotes that Khamisi relates speak to big issues such as tribalism, theft of public resources, political chicanery, cultural changes, without preaching.

The way it is told captures the image of a man happy with his life. Very few people today, especially politicians, would say they are fully satisfied with what they have achieved.

BEST RUN CONSTITUENCY

And yet Khamisi doesn’t brag in his book. He is more grateful to his God for blessing him to succeed in life despite, for instance, having failed to pass the end of secondary school education examination.

Lack of academic progress didn’t stop him from working as a journalist, tour company owner, a diplomat and a politician whose Bahari constituency was voted the best user of the Constituency Development Funds for all the years he was the MP.

Khamisi tells a straight story about the hardships of growing up in a family with separated parents, struggles of living with a stepmother, going to school, failing to pass examinations, getting a job whilst young to lessen the family burden, living in the shadows of a politician father, travelling to America, studying again, getting married, starting a family, hardships of losing a job, starting a business, closing it down, joining politics, betrayal by voters, loss and the consequent pain and settling down in US to write books.

Such is the rich life of this descendant of “foreign” slaves; this book is worth reading, even if it is simply for knowing a little bit of the ethnic and cultural mixed pot that is Kenya today.