Twin sisters helping parents understand dyslexia

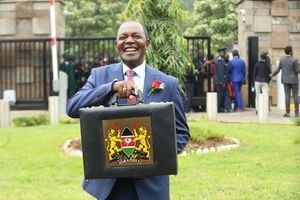

Nancy Muringo (left) with her sister Phyllis Munyi founded Rare Gem Talent Primary School in 2010 to teach children with dyslexia. The school is located in Kitengela, Kajiado County. PHOTO | FRANCIS MUREITHI | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Experts say most children with dyslexia have difficulty in more than one area of cognitive abilities.

Only five per cent of dyslexics are usually diagnosed, partly due to lack of knowledge about the condition and the stigma around it.

Some of the signs to look out for include, whether the child has difficulty tying shoe laces; whether they have directional confusion like inability to tell left from right, or up from down; and whether they mispronounce words, especially those with lots of syllables.

When Felix Kariuki was eight years old and just beginning his schooling, he used to receive beatings from his mother for failing to read and write properly.

His mother, Phyllis Munyi, often ran out of patience with the “stupid” boy and she caned him many times, convinced that he was lazy and did not want to follow study instructions.

COMMUNICATION

“Talking to my son, he was very bright and would make sense of verbal communication, but when it came to writing or reading, he was doing the opposite. He read what was not in the book and even wrote unreadable things,” Phyllis narrates to Lifestyle.

She should have known better.

It took time before she came to discover that her son had dyslexia, a condition that causes difficulty in the mind’s interpretation of text. It is a common phenomenon that is often not identified for what it is.

According to Dyslexia African, a Nairobi-based organisation that handles the correction of dyslexic children, only five per cent of dyslexics are usually diagnosed, partly due to lack of knowledge about the condition and the stigma around it.

Phyllis’ lack of information on her son’s condition caused trouble for long. But out of the testy times, today a school stands in Kitengela, Kajiado County, dedicated to educating dyslexic children.

Called Rare Gem Talent Primary School, the facility that is owned by Phyllis and her twin sister opened doors in 2010.

It started with 20 students and has since grown to a secondary school, with over 100 dyslexic students.

LAUGHING STOCK

In those years of uncertainty when she agonised about her son’s learning curve, Phyllis even had to change her son schools, thinking teachers were not giving him the right attention. Maybe, she thought, they were not teaching the correct concepts.

The situation persisted and even got worse. The boy could not read a word. She did not want to tell anyone about it since she would get embarrassed whenever she heard anyone saying that her child could not read.

She contacted her twin sister Nancy, a teacher, to give her son special tuition so he could learn to read and write.

By this time, Felix had stopped going to school. Whenever he read or wrote anything in class, his colleagues would burst into laughter, which made him the laughing stock.

A shared problem

“When I confided to my sister, I was surprised that her first son, Martin, who was 11 years old, had the same problem. My sister, being a teacher, would train her son in the house and he was way better in reading and writing compared with my son,” Phyllis explains.

Being a trained teacher, Nancy knew the condition her son was suffering from — dyslexia — as she had come across many learners with the same problem. What she did not know was that her nephew Felix, a son of her twin sister Phyllis, had the same problem.

Students at Rare Gem Talent School in Kitengela take part in a practical lesson of knitting during their free time. PHOTO | FRANCIS NDERITU | NATION MEDIA GROUP

However, Felix and his cousin Martin had different reading challenges. Felix (now 21) was not able to match sounds with letters while Martin (now 24) found it difficult to recognise words by sight. Martin was also very slow in reading. Experts say most of the children with dyslexia have difficulty in more than one area.

“It is often said that behind every successful dyslexic is an invested and persistent mother (or parent). Not only did I fit the description, but I also ensured that I brought my son to the school I was teaching at and ensured that I gave him the attention. Yet, despite these and other unique advantages, my son’s educational journey was still extraordinarily difficult,” says Nancy.

“Parents of dyslexic children are hit hard with the reality that their children are not able to read and write,” she adds.

The parents’ pain is often compounded when their dyslexic children are humiliated by teachers, their peers and even the rest of the community.

Nancy says: “I wish I could say that being a teacher allowed me to be more clear-eyed about my son’s challenges, but that was not the case. I was hurting inside.”

Signs of improvement

With the pampering and encouraging messages that Felix got from his aunt Nancy, he had to be left with her for coaching. After four months, Felix was able to write and spell a few letters, a big improvement.

“I was torturing my son yet it was not his fault. Had I known that, I would have looked for a special teacher for him. It is a big mistake that most parents make unknowingly,” says a remorseful Phyllis.

The twin sisters ensured that their sons were given the attention they needed. They even enrolled them for coaching so they could improve in their literacy skills.

The two boys were never enrolled in special schools. They were left in normal institutions to attend normal classes, which saw their skills improve by the day.

“People wondered how we managed,” recalls Nancy.

RARE GEM

Children with dyslexia have learning difficulties and cannot write or read fluently. Dyslexia African calls the condition as being “both a gift and a challenge” because much as they encounter difficulty in spelling, writing, reading, doing mathematical calculations and handling tasks that require deep concentration, they are usually good with art and other hands-on learning.

Nancy says that when they noticed an improvement in Felix and Martin, they were impressed. “We encouraged the teachers to be patient with them since they are slow learners and it takes time for such children to master words and letters,” Nancy says.

She personally went to school and explained to the teachers and her son’s colleagues that the two had a special condition that made it tough for them to read and write.

Explaining their condition to the learners changed things. The classmates stopped mocking the boys and, often, they would alternate in helping them to read and write. “Most parents always mistake the children for being stupid, lazy or that they do not just want to work. But in reality, it is just weakness and inability to comprehend texts,” Nancy explains.

Given the remarkable improvement, teachers at the school would refer children with the condition to Nancy to help them.

“I got several referrals of children with the condition and I would coach them at home. When the numbers grew, we sat together with my sister and registered a school to provide a solution for learners who have dyslexia and other specific learning difficulties,” Nancy says.

That is how Rare Gem Talent Primary School was born. The school was started shortly after Phyllis and Nancy formed the Dyslexia Organisation Kenya, through which they create awareness about the condition.

Rare Gem Talent School in Kitengela. PHOTO | FRANCIS NDERITU | NATION MEDIA GROUP

“Every person with dyslexia needs to find the mental strength to get through school. The first step on that journey is to understand dyslexia and rediscover the self-belief and determination to succeed. Individuals with dyslexia benefit from a supportive environment combined with an individualised, multisensory programme of learning, structured into small steps,” says a post on their website.

Out of her desire to know how to handle her students better, Nancy has since gone for specialised education on managing dyslexic children.

The first Standard Eight class at the school sat their Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) examination in 2017, with the best student scoring 175 marks out of 500.

“This is a clear sign that they can compete with normal students. However, we are not concentrating so much on their education but giving them the skills to do better in life,” Nancy says.

In the morning, the students are taken through the 8-4-4 syllabus. In the afternoon, they have time to venture into their talents — for instance modelling, sewing mats, drawing, singing, and dancing.

“We have great talents here and rather than concentrating on something that may not help them, we have decided to get the best talents out of the students. They are excellent on the skills sides. They are doing fine,” she says.

There are high-frequency sounds, for instance “a”, “b” and “d”, which disorient dyslexic children while reading. Unfortunately, almost every sentence normally has such words. The words do not create images in the minds of dyslexics, hence triggering fear and disorienting them.

After being taught through those delicate parameters, Felix and Martin finally knew how to read, albeit with small challenges. Felix is now at Kabete Technical Institute, determined to excel in other disciplines.

NO CURE

Many experts attribute dyslexia to brain damage or injury, though the exact cause is not known. Others suggest that it is mental gift out of a genetic condition.

“There are different types of dyslexia: mild, moderate and severe. Our sons had mild dyslexia and that is why it was easy to get them back faster. Those with severe dyslexia take time and at times it can take forever for them to come back,” says Nancy, who is now a dyslexia expert.

And what does she think caused dyslexia in Felix and Martin?

“In our case, it was genetic. It was hereditary and early diagnosis and intervention really helped us to prevent and reverse a lot of challenges caused by dyslexia in an individual,” she says.

Dyslexics think predominantly with the right side of the brain, which helps them express themselves and solve problems in a more creative manner.

Dyslexia, those who have mastered it say, does not limit the possibilities of a person making an impact in life.

Unfortunately, there is no cure for it. To cope, dyslexics are given special reading glasses to help them surmount their learning weaknesses.

On the website run by Phyllis and Nancy, there is a form to enable parents assess dyslexia in their children.

CONFUSION

Some of the signs to look out for include, whether the child has difficulty tying shoe laces; whether they have directional confusion like inability to tell left from right, or up from down; and whether they mispronounce words, especially those with lots of syllables.

The form also asks parents to state whether their children have difficulty remembering spoken information; like if they forget what they have just been told. It also encourages parents to check whether their children exhibit persistent reversal of letters and numbers when writing, for example “b” and “d”; “p” and “9”; and “L” and “7”.

“My son’s story may demonstrate that dyslexia doesn’t have to be an academic death sentence. Students shouldn’t require a teacher mother to navigate the system for them, either,” says Nancy.