Mulli, 94, braved the knife for a successful hernia surgery

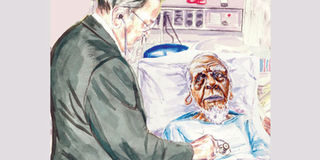

The day I operated on Mulli, I was on tender hooks, did not sleep that night, worrying about the old man. ILLUSTRATION | JOHN NYAGA

What you need to know:

- I analysed my own feelings and concluded that in trying to dissuade Mzee from having surgery, I was assuaging my own fears; I had never operated on a man of 94.

- My highest record was a woman, aged 91, on whom I had done a mastectomy for breast cancer and she lived to be 100 and died of virus pneumonia!

Are you sure, you are 92? You certainly don’t look it,” I said as I saw the birth date entered in the file of my new patient, Andrew Mulli.

“My real age is 94.” Mulli replied to my surprise and explained. “There was no compulsory registration of births in the early part of the last century when I was born. When you went for your passport, which I did, the immigration officer decided your year of birth by what age he thought you were!”

“I would thank my lucky stars if I look anything like you, if, and when I reach the venerable age of 94!” I replied reminding him of what I said to a woman under similar circumstances. Muthoni brought her mother of 90 to see me, who looked very young for her age. I turned to Muthoni, who was a staff nurse on my ward and stunningly beautiful, and I said. “If you look anything like your mum when you are 90, I will go on my knees and propose to you!”

EXAMINATION

Having made Mzee comfortable with these complementary remarks, I read the letter which Mulli had brought from his GP in Kangundo, which read: ‘I am sending this grand old man of Kenya with what looks to me like an inguinal hernia. He wants something done for it. Please take over.’

“What’s your problem Mzee?” I asked wanting to hear directly from the horse’s mouth.

“I have a lump in my right groin, which appears when I am standing or walking and vanishes when I lie down.”

“How does it bother you?” I asked

“It hinders my walking and I like walking because that is the only exercise I can do now,” Mulli explained.

I obtained a full medical history, which included wife dying 10 years back from high blood pressure and diabetes and his two sons being well and settled, one in business and the other with his sugar factory.

I then examined Mulli. “I want to examine you standing and lying down,” I advised, exactly like I teach my students; hernia in the groin appears when the patient is standing and disappears when he lies down.

“Cough,” I said to him as he stood by the couch holding his trousers, as I saw a bulge appearing in his right groin and disappearing when he lay down. “What is it?” Mulli asked as he sat up after I completed my examination.

HERNIA

“Your full diagnosis is a right reducible complete inguinal hernia.” I thought I was examining under-graduate students. “All the terms in that diagnosis are self-explanatory except ‘complete’ which means the hernia descends into the scrotum.”

“What is a hernia?” Mulli asked, surprising me by his curiosity at his age.

“It is a weak point through which the contents of the abdomen pass down into the groin and then into the scrotum,” I explained.

“And the treatment?” Mulli inquired.

“Normally, it is surgery to repair the weakness, but in your case we might have to tailor the treatment to your age. I was thinking in terms of a truss which when applied will hold the contents of your hernia in and prevent them descending down. I am worried about the complications of surgery and anaesthesia at your age” I explained.

“But my GP sent me to you because she claimed that you have no complications,” Mulli said.

“It is nice of her to say that,” I replied feeling proud at my past student having utter confidence in her Mwalimu, “but like all drugs have side-effects, all operations have complications and in your case surgery is not lifesaving as it would be if you were suffering from cancer which needed surgical intervention to cure you.”

Then to emphasise the point I was making, I added. “I don’t believe in the adage which says that the operation was successful but the patient died!”

I analysed my own feelings and concluded that in trying to dissuade Mzee from having surgery, I was assuaging my own fears; I had never operated on a man of 94.

My highest record was a woman, aged 91, on whom I had done a mastectomy for breast cancer and she lived to be 100 and died of virus pneumonia!

At this point, let me justifiably digress and add an interesting episode related to her. After a few annual visits, the daughter asked if her mother could see me less frequently.

Presuming that they could not afford my consultation fees, I said: “I could waive my fees.”

The daughter replied: “It’s not your consultation fees we can’t afford. Since you called the dress she was wearing the first time she came to see you as maridadi, she wants a new dress every time she comes to visit you and buying even from mitumba is becoming expensive!”

NERVOUS

It came out in subsequent discussion that Mulli was bent on having surgery and did not want to be lumbered with a truss for the rest of his life. “It is like life imprisonment,” he lamented. His will prevailed after I made sure that he was aware of all the age-related complications.

The day I operated on Mulli, I was on tenterhooks. I did not sleep that night, worrying about the old man. I did not enjoy my meagre cereal breakfast and when I went to see him next morning, I was not sure what I would find. I needn’t have worried, because I found my nonagenarian patient, sitting up in bed enjoying his full English breakfast of eggs, bacon and sausages! “Good morning. How are you feeling today?” I greeted him.

“I am fine,” replied Mulli, and added. “You saw me a few times yesterday and every time you came, you looked worried.”

“I was very worried about you,” I decided to make a clean breast of it.

“You shouldn’t have because I come from a good stock,” Mulli replied. “Longevity runs in my family. My father lived to the ripe age of 105! I want to make a century.” And he did.

Six years after his hernia operation, Mulli reached the milestone he was looking forward to and his two sons threw a party in Machakos to celebrate the occasion.

I received an invitation card which had an interesting postscript which said. ‘No gifts please; just your blessings for many returns.’

I drove to Machakos on Saturday morning and attended a grand function with drinks galore, sumptuous buffet with nyama choma, among other delicious items.

Thankfully, only two speeches were scheduled by each of his sons but Mulli was persuaded to speak after his sons finished. I had never heard my patient speak in public before but I was pleasantly surprised to hear Mulli because his speech contained a lot of humour and at the end he shared with his audience the secret of his long life.

As he reluctantly got up to speak, one son brought a chair for him to sit and speak from while his other son brought a stool to put the microphone on a stand so that Mulli did not have to hold the gadget while he spoke. As Mulli sat, I heard him complain. “If I had known I would have made a few notes. Now, I will talk from my heart and not from my head!”

ADVICE

As he made himself comfortable on the chair, he continued. “The advantage of this funeral party of mine is that I have been able to invite all my friends, personally selected by me.” As his listeners laughed cautiously, he went on. “I feel as happy today as the day I got married and brought Sally home with full Akamba rituals.” He then introduced a brief melancholic note. “It is a pity she is not with us today to celebrate my century on God’s earth.”

He quickly regained his composure and reverted back to his style. “I know why you pressurised me to say a few words; You want me to give you the alchemy of my longevity, so here is the prescription.”

He took a long time to articulate the psalm of his life and while he was doing it, as an afterthought, he added, “I should charge you for these tips.” Furtively glancing at me, he continued.

“You would have to pay a fortune if you went to a doctor to get the prescription which I am giving you free of charge.”

After keeping us in suspense for a while, he came down to brass tacks. “My first tip is not to give up work altogether; keep working, at least part-time. When I am in Kangundo, I travel to Machakos to go to my son’s travel service every day and help him with his accounts. In Muhoroni, my driver takes me to the farm where I look after the farm workers. I believe in moderation in everything I do. I walk every evening until I am short of breath to put my heart and lungs through their paces.” He then divulged his innermost secret and said. “I indulge in a Singh-size tote of whiskey every evening before my dinner.”

Then, as he brought his talk to an end, he added. “Treat your body like your car which you take for servicing every 5,000 miles. Once a year, give your body an executive check-up.”

Mulli ended the talk by making two more important points. “I must warn you that it is better to shed your load gradually, otherwise you will find yourself suddenly and precipitately redundant. My final point is to arrange your finances for your retirement.” Then with a chuckle, he ended his talk and said: “Remember the inflation factor!”