Little pad making a big difference

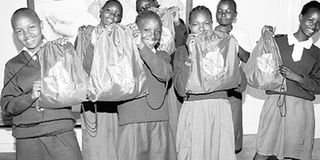

Girls from St. Elizabeth Mukuru Primary School in Mukuru kwa Reuben show off their kits. Photo/DENNIS OKEYO

While addressing the African Union Summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in January, UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon said, “…We must invest in women and girls. When we empower women, we empower Africa. Let us make sure that girls stay in school, and that this generation can complete secondary education.”

Yet a study conducted by the Federation of African Women Educationists (FAWE) in 2005 found that approximately 500,000 girls in Kenya miss school every month because they cannot afford sanitary protection.

Then, in 2008, Proctor & Gamble, the distributors of Always sanitary towels, partnered with the Girl Child Network (GCN), a local NGO, in a project to provide free disposable sanitary towels to 15,000 girls from more than 180 schools around the country.

The company then conducted a survey to assess the impact of the project. Schools covered by the project confirmed that the girls had been able to attend school even during their menses,” according to its external relations manager, Bob Okello.

“They were also able to concentrate better in class and get better grades because they felt more confident and able to understand and appreciate the changes taking place in their bodies.”

Studies conducted over the years by the Forum for African Women Educationalists-Kenya (FAWE-K) show that most Kenyan societies have no system for preparing girls for their first period since the topic is still not publicly discussed.

“For most of the younger girls, menstruation comes as a shock and peers seem to be the main source of information,” says Pamela Apiyo, the national coordinator of FAWE-Kenya, adding that the information is often distorted.

“Indeed, from studies we have carried out, up to 71 per cent of school going teenage girls have inadequate knowledge of menstruation and how to manage it,” she notes.

“This has impacted negatively on girls, both psychologically and socially, and thus affects their learning and advancement in education.”

Worse still, girls who lack proper sanitary protection miss between three and four days of school every month.

“So the availability of sanitary pads determines whether or not a girl will remain in school,” Apiyo observes.

Women’s health

Lack of sanitary protection not only affects women’s education, but also their health. Dr Njoki Fernandes, a gynaecologist in Nairobi, says research shows that of the 10 million females in Kenya between the ages of 12 and 50, only 30 per cent use a hygienic sanitary pad.

“Lack of knowledge as well as the cost of pads are cited as two major reasons for lack of usage,” says Fernandes.

She is concerned that most of the unsanitary materials that women use expose them to the danger of infections.

“In the course of my work, I have met many women suffering from fungal infections because they use unhygienic sanitary materials. As a result, their relationships have been affected negatively because their partners suspect that they have sexually transmitted infections,” she explains.

To helps save the situation, Huru, a project run by Micato Safaris, began making re-usable sanitary towels for needy schoolgirls. The project, located at the heart of Mukuru kwa Njenga slums in Nairobi, has been operational for two years and has so far benefited about 1,600 girls.

“The idea of seeking a sustainable solution to girls’ menstrual woes came from a need we had noted, having been here for more than 20 years,” says Cliffe Lumbasyo, the programme director.

The re-usable towels project is an idea that Lumbasyo would want replicated in other East African countries because the problems faced by schoolgirls in the region are similar.

“We would like to expand to Ethiopia, Tanzania, Uganda and the rest of Eastern Africa since school girls face the same issues with their menses and sanitation,” Lumbasyo explains.

This, he adds, can only be achieved through partnership with like-minded individuals and organisations. So far, Johnson & Johnson, the GCN and Warner Brothers have sponsored some of the kits that have been distributed to girls in schools in Kakamega, Homa Bay and about three within Mukuru Kwa Njenga.

The Huru re-usable sanitary towels come in kits comprising eight reusable sanitary pads, five for regular use, and three are for overnight use. Also included are three pairs of underwear and a bar of soap for washing the pads.

To complete the kit is a waterproof ziploc bag for carrying the pads as well as an educational insert in English and Kiswahili that contains information on HIV/Aids prevention and an overview of fundamental aspects of a young woman’s sexual and reproductive health.

“A single kit goes for only $20 (Sh1,520) and can last a year with proper maintenance,” says Lumbasyo.

The Kenya Bureau of Standards (Kebs) is yet to certify the kits since it is still developing the standards for re-usable sanitary towels in the country. Lumbasyo says he has taken some samples to them and they are working on the standards.

The Huru workshop at Mukuru kwa Njenga manually produces between 1,000 and 1,200 sanitary towels a day. The project employs 17 people, eight men and nine are women.

“Although this is a women’s empowerment project, our message to the world is that menstrual issues are not a woman’s problem but a societal one, and that is why it needs to be jointly addressed by society. When a girl misses classes or drops out of school due to issues emanating from lack of access to sanitary towels, then the future of this country and its economy suffers,” Lumbasyo explains.

The lack of access to sanitary towels is not just a problem for girls from poor backgrounds, but even a sizeanle number from middle-class families. Lumbasyo says that many parents rarely think of giving girls an allowance for sanitary pads.

However, he sees the problem as largely afflicting women and girls in rural areas and informal settlements due to their low purchasing power.

Indeed, the Ministry of education has seen the benefits of giving out free sanitary towels to schoolgirls. In May last year, the ministry partnered with Always in a nationwide project that saw 20,000 girls in their last two years of primary school access free sanitary pads.

The nation-wide project targeted school girls in slums, arid and semi-arid areas and internally displaced persons since they are the ones who feel the impact of poverty on their education,” explains Okello.

When free sanitary towels were distributed to girls at St Anne’s Ahero Primary School in Nyanza Province last year, the effect was tangible.

“The girls in Standard Seven and Eight who received them were more comfortable and became very confident. They became more active in class and in some extra-curricular activities they previously shunned,” explains Pamela Onyango, a teacher at the school.

Their attendance also improved. “Absenteeism dropped to a minimum and some ‘sicknesses’ disappeared,” she adds.

The Huru project hopes to expand to enable more girls to remain in school, but this can only be realised if “like-minded partners come on board as our goal is to spread our wings. But no matter how long it takes for a sustainable partner to come a long, we are not stopping here. He or she will find us on the move,” Lumbasyo asserts.