MY STORY: Beacon of hope for autistic children

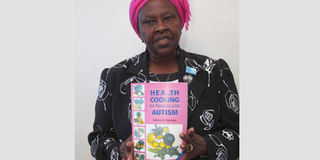

Autism Society of Kenya founder Felicity Nyambura Ngungu on March 29, 2019 holds her book on nutrition for people with autism. PHOTO | KANYIRI WAHITO

What you need to know:

- When my daughter gave birth to her first child, Andrew, I noticed something was amiss.

- We consulted many specialists, who dismissed us, saying he was fine and that he would outgrow it.

- When we took him to baby class, we were told he was a spoilt child because he didn’t interact easily.

Felicity Nyambura Ngungu is the founder of Autism Society of Kenya. As the world marks Autism Awareness month this April, she shares the story of how her grandson inspired the creation of the first autism advocacy initiative in Kenya.

“I am a mother of five — four daughters and one son. When my daughter gave birth to her first child, Andrew, I noticed something was amiss. I had experience with primary healthcare so it was easy to observe he was not meeting basic milestones. He was underweight even though he was breastfeeding adequately. He was also averse to touch and eye contact (even when breastfeeding). He would not cry or make any sounds that suggested language development.

"At the age of six months, he started crying uncontrollably. It was not until he was two years old that he started saying the word mum. There was nothing wrong physically but he was not moving — if you placed him somewhere he would stay at that spot until you moved him. He started standing up with support when he was two and a half years.

"We consulted many specialists, who dismissed us, saying he was fine and that he would outgrow it. When we took him to baby class, we were told he was a spoilt child because he didn’t interact easily. At the age of three, one doctor said he was ‘mentally retarded’. We eventually took him to a private school, where he made some progress.

"When he was around 12, he cried a lot, and hardly slept. By this time, I had retired and had a lot of time in my hands so I took over most of the care. We took him to a special education institution and once again, we were told nothing could be done for him. By this time, we had spent so much money on consultations and private schools that we even sold some property. The problem I have with doctors is that not many of them are willing to say ‘I don’t know’. I was told he was acting like that because we had neglected him.

SPECIALIST

"When he was 15, we saw a specialist who was apparently the best in the country. They said the brain scans showed that Andrew was ‘retarded’. But as I was coming from that clinic, a nurse ran after me and told me, 'Don’t believe what you have been told. On Friday, I want you to go to Gertrudes Hospital. There is a doctor who goes there called Professor Forbes. He might be able to help you.'

“So on the material day, Andrew and I set off for Gertrudes. We used public transport because we had sold our cars.

“Andrew was strong, unruly, but non-verbal. The only word he would say was ‘Cucu’. That is why everyone calls me ‘cucu’ to-date. By the time we arrived at the hospital, Andrew was tired and hungry. He became uncontrollable. He was all over the place, picking and dropping things. I tried to contain him but Forbes held me back and told me to let him be. I just started crying. After I calmed down and told him my story, he said, “By the way, your grandchild is autistic.” That was the first time I ever heard that word. That was the beginning of my journey with Autism.

“My family and I did a lot of research. By this time my daughter had already moved to United States so she was able to find and share resources with us. The first thing I did was change Andrew’s diet — I eliminated wheat, dairy and sugar. We then recruited an occupational therapist who shadowed Andrew and helped him with things like exercise and social engagement. I called some parents whose children went to the same special school as Andrew and told them we were going to fashion a diet for our children.

“After six months of this diet and occupational therapy, Andrew calmed down. For the first time in many years, he started having a normal sleep pattern. One day he was at a supermarket with his therapist James and they ran into a journalist, who had met Andrew before. The journalist asked James, “Which hospital did Andrew go to?!” James said, “He didn’t go to hospital. He lives with his grandmother who has put him on a diet.” The story was featured on TV and got publicity. A support system blossomed. We had 52 parents of autistic children meeting in my house!

LOBBY

“Then we thought that such a thing ought to exist in public schools because the government should be helping such children. We started looking for support. We met the then health minister and her secretary, who advised us to lobby more effectively. I went to the registrar of NGOs. At first I even had trouble convincing them that autism was a real disability. But after several unrelenting visits, Autism Society of Kenya was registered. By this time a lot of parents had grown weary and only six of us were remaining.

"After numerous meetings with City Hall officials, we were finally given space at City Primary to set up our programme for autistic children. Word spread and the Commonwealth Education Fund and a few corporates came in to support us. The programme kicked off and parents started coming. City Primary, a pilot project which is set to be replicated in other counties, started operating in earnest.

“With the support of UNDP, we set up support groups in 21 counties. One of the biggest milestones for me was when we got word that autistic children were being abandoned or killed in Samburu and Turkana. With the support of local NGOs who work in the area, we spent three weeks in manyattas sensitising locals on autism, and thus the killings stopped. We now work closely with a network of other developmental disabilities to lobby the government for support.

“I receive phone calls from parents at midnight asking me what to do with an uncontrollable child. I get phone calls from police over lost children they suspect to be autistic. We have doctors who call us to consult on cases. We have a funding proposal in the pipeline with the ministry. Once that money comes, we will establish clinical guidelines for doctors to identify autism — especially from ages 0-5 because early detection and intervention is necessary. Andrew, the inspiration behind all this, has since joined his mum in the US, where he continues to receive adequate care.”