Breaking News: KDF chopper crash kills five

Not a laughing matter: How Kombani waded into humour

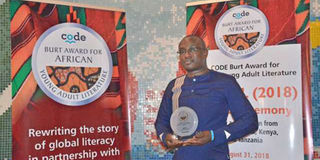

Writer Kinyanjui Kombani. PHOTO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Humour, Kombani would later say, is not his preferred genre and here he was being needled to wade into the water.

- The other reason for Kombani’s trepidation was the gargantuan name the prize is named for.

It is hard to imagine a writer as prolific as Kinyanjui Kombani — an author with more than 13 books bearing his name, and with several prestigious literary awards, including the CODE Burt for African Young Adult Literature — developing jitters at the suggestion by his publishers to write a novella.

But this was no ordinary novella; Kombani was being challenged to write a book for consideration for the Wahome Mutahi Literary Prize: meaning humour was the rider.

PREFERRED GENRE

Humour, Kombani would later say, is not his preferred genre and here he was being needled to wade into the water. For the first time, the author found himself in the grip of the dreaded writer’s block.

“My first reaction was a no. Having written ‘more serious’ work like The Last Villains of Molo and handled dark thematic concerns like extrajudicial killings, I was readying myself to settle for the ‘dark writer’ tag,” says Kombani. “But they insisted, and in fact the editor told me he had pitched their idea to the board. I had no option but to write or lose my credibility.”

The other reason for Kombani’s trepidation was the gargantuan name the prize is named for. Wahome Mutahi, who died in 2003, was one of the most notable authors, satirists and playwrights in East Africa. Indeed, his column “Whispers”, which debuted in the Daily Nation in 1984, was, until the writer’s death, voted yearly the most popular column in the East African region.

SILVERWARE

“I felt that any work that even hopes to be associated with Wahome Mutahi needs to be as great as his own work,” Kombani confesses. To fortify the argument was the fact that the prize was not handed out: none of the entries met the threshold for the silverware.

With some encouragement from his mentor John Sibi-Okumu, Kombani, 39, went to work. A huge fan of the “Whispers” column, and also having read Wahome’s novel Three Days on the Cross, Kombani replayed what made Mutahi’s work stand out: simplicity, characterisation and message.

It is with this approach that Kombani set out for his novella, Of Pawns and Players, the eventual winner of the 2019 Wahome Mutahi Prize.

“When I set out to write my manuscript, I stuck to the ideal of making the storyline simple and straightforward: a man who sells mutura (stuffed cow intestines) by the wayside gets drawn into a betting syndicate,” says Kombani. “In fact, some of the book’s readers have dismissed it as ‘nothing more than a high school composition”.

During the research for the novella, Kombani says he was overwhelmed by stories of misery.

BETTING

“I got in touch with people who had lost their livelihoods through betting. As part of my research, I signed up to several betting apps and lost quite a bit of money myself.”

“I discovered why it is easy to get addicted — because you win some money and think you are on a winning streak, until you lose it all. I was also more conscious of the media messaging around betting.”

He adds that during his betting adventure, he learnt a lesson lost to most of the non-betting population: “It takes a high level of intelligence and awareness to bet … I needed to have all this in the story, and that is why, to the chagrin of many people, I don’t let the characters fall in love and live happily ever after.”

In the portrayal of the protagonist — the ‘mutura’ seller — Kombani says it was also an indictment of the society, who will see roadside food vendors as dimwits, not capable of outsmarting the ‘players’. Just as fans of “Whispers” would soon learn each time, nothing is as it appears.

STRONG MESSAGE

“I am happy that the judges saw the value of a simple story with a strong message,” he says.

On September 28, Kombani rose to receive his gong, having galloped past seven other entrants. It felt surreal, he admits: winning an award named for his childhood hero. But it also served a lesson; that elasticity in literary genres is possible. “I was venturing into a genre I was not comfortable in,” he says.

In addition to the prize money, Kombani says the biggest perk is the confidence and esteem winning the Wahome Mutahi Prize has brought him.

“I hope it also spreads the word to other writers that it is indeed possible to succeed in this,” he adds.

It has been a twin-blessings season for Kombani: around the same time he won the Wahome Mutahi Prize, he was also crowned the winner of the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature for his young-adult fiction novella Do or Do.

CAREER BANKER

Unbeknown to many, writing is Kombani’s night job. A career banker, the author has managed to juggle his banking duties with his writing. He credits this to his employer. “I am lucky to have an employer who values the work I do outside the bank and who does not see my writing as competing with my bank work.”

Writers live forever, we pose to Kombani. So, what would his legacy be? “I haven’t thought this far,” he demurs. “Food for thought.”

A literary lodestar for future writers, like Wahome Mutahi was to him perhaps? For now, the awards will do.