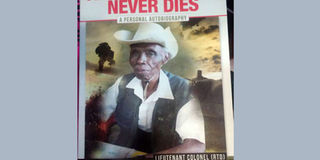

An Old Soldier Never Dies: Colourful memories of a retired colonel

Photo of the book 'An old soldier never dies'. PHOTO | JEFF ANGOTE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Kiambuthi is one of the few Kenyan soldiers who have taken the uncommon step to tell their stories.

- He peppers his narrative with hilarious anecdotes, including the fact that he is not sure who his biological grandfather was because his grandmother had walked out of her matrimonial home when she begot Kiambuthi's father.

- At the heart of that story is the question of identity.

Memory can be a luxury, especially when age catches up with one and the escapades of one's youth begin to recede surreptitiously into the recesses of the mind. However, for Lieutenant Colonel (rtd) Geoffrey Kiambuthi Kinuthia, whose memory is still sharp and whose pen is agile, the days of his youth remain clear like a blue sky on a sunny day.

"Good memories are the most precious of treasures," he writes in the preface to his self-published autobiography, An Old Soldier Never Dies, which came out barely a month ago. "Nurtured and caressed, they remain with us; like favourite books to be plucked from a shelf and enjoyed."

Kiambuthi is one of the few Kenyan soldiers who have taken the uncommon step to tell their stories. And he peppers his narrative with hilarious anecdotes, including the fact that he is not sure who his biological grandfather was because his grandmother had walked out of her matrimonial home when she begot Kiambuthi's father.

"That story is not a fictional folktale but is as real as I am sitting here writing it and, to be honest, was quite traumatic when I was first told about it."

At the heart of that story is the question of identity. Who was he? Did he belong to Kinoo, the village where he was born in Kiambu, or was he an outsider on account of the fact that his father had roots at the Coast? And could this, in the final analysis, have informed his decision to eventually settle in Kilifi after he voluntarily retired from the military in 1980?

Kiambuthi's story is not your usual autobiography. It is told in episodes as his memory guided him. One of the hilarious bits is the story of a villager called Kaniaru, who had consulted a witchdoctor because he was obsessed with the question of his own death. The witchdoctor warned him that his death would be caused by a buffalo.

So when a buffalo was spotted in their village, he was guided to safety as the animal was speared to death and its head chopped off. When Kaniaru's friends called him out to see the animal, he slipped on the entrails and fell onto the buffalo’s head. The horns pierced him as he fell and he died instantly.

As a young boy, Kiambuthi had many encounters with the military during the colonial times. One of his uncles fought in the first World War in Tanzania before deserting. And as a boy, he was accompanying his father to Nairobi when he came across British soldiers in their ceremonial uniforms, and in his mind, they looked like gentlemen.

He could not reconcile the image he was seeing with the reputation of the soldiers in their hunt for the Mau Mau.

And on his first day in school, he was caned because he had failed to make a proper left turn when assembly was dismissed. Unknown to the boy, he would one day become a soldier, although the influences that would lead him in that direction were all around him.

In high school, Kiambuthi enjoyed English literature, reading Shakespeare and DH Lawrence.

"My only worthy rival (was) a quiet boy called Peter Mwaura, who eventually became an illustrious journalist," he recalls. Mwaura would later rise to become editor-in-chief of the Nation Media Group. He is currently the group's Public Editor.

The author's military life is equally colourful.

"During registration at Sandhurst," he writes, "I was found to be underweight. I was therefore entitled to a pint of milk every morning."

It was also at Sandhurst that he met his future wife, Elizabeth Wanjiru, who was training as a nurse in Warwickshire.

Kiambuthi's last posting was at the Armed Forces Training College, Lanet, where he served as Commander of the Combat Wing under General David Tonje, who was then the commandant. He did not last there long before resigning.

"I passed the ridge of prosperity and honour, and began to rapidly descend the other side," he writes. "I was completely unprepared for the rigours of the civil street."

In the end, he tried many business ventures which failed before eventually starting a school which is flourishing to this day.

"That is the mixed bag that is my past," he writes, and how rich and hilarious it is.

Kiambuthi’s book should serve as an encouragement to others who feel strongly compelled to share their life stories. What is more, it is not your usual style of writing. This is a narrative that any reader will enjoying sinking their teeth into for it looks at the good as well as the bad in his life.

Of course, he has also had a colourful public life, including an unforgettable moment with Kenya’s founding president Jomo Kenyatta, who needed an intelligence brief from him, and former Ethiopian leader Haile Selassie and other public figures, which situates him in the public space. But he is also careful in selecting what to tell and what to keep close to his chest.

This is a book stores should stock.