First tour of Nigeria and a moment with Prof Wole Soyinka

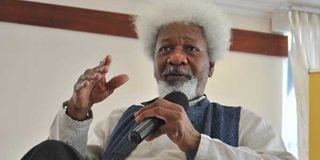

Nigerian writer and Nobel Prize Winner Wole Soyinka. PHOTO/FILE

What you need to know:

- The Nigeria International Book Fair was the third player in the conspiracy.

- For it was the chief reason I left Iseyin a couple of days earlier than expected. Armed with a list of books and dozens of WhatsApp images of shea butter and Ankara fabric my friends expected me to take back home,

- I set forth for Lagos hoping to, among other things, catch the literary discourses at the Book Fair.

- Even then, I was still oblivious to the fact that in less than two days, my bucket list would get two new blue ticks.

I did not pack my copy of Fresh Paint, Amka Volume 2 as I selected books to carry to the Ebedi Writing Residency. Though the book contains my poem ‘Scarlet Road,’ it did not occur to me that I’d get to meet, let alone sit and chat with, Prof Wole Soyinka on my first visit to Nigeria.

Even if I met him, it would be a long shot to expect Prof — as I heard him being referred to by those in his office — to have time to sit and listen to how his poem ‘Death in the Dawn,’ had inspired ‘Scarlet Road,’ my 2013 poem about the journey of disenchantment from Kenya’s independence to when she turned 50.

“Much of Soyinka’s verse cannot fully be understood without some knowledge of the Yoruba background,” writes Adrian A. Roscoe in his book Mother is Gold — A Study in West African Literature. If I am to take Roscoe’s words literally, then I can say that in retrospect, my literary excursions during my stay in Nigeria were preparing me for this meeting.

First was my visit to the University of Ibadan, where a friend, the playwright and 2012 Caine Prize winner Rotimi Babatunde, had invited me to a highlife music concert. Sitting at the staff club at UI, I had wondered if, perhaps, the Mbari literary club ever sat at the table we were sitting on. On my second visit to the university, Babatunde — who shares a name with Prof Soyinka — would drive me around the campus, and narrate to me the history of the place.

Second was my stay in the Yoruba town of Iseyin, Oyo State. In the weeks there, I learnt quite a bit about Yoruba culture; the names and roles of the deities; the traditional king and his influence over the town, the cuisine, the aso-oke fabric; a well-loved traditional woven fabric originally from Iseyin and, finally, thanks to the electrifying performance by secondary school students of Alalukimba Academy, the centrality of the ‘talking drums’ to Yoruba festivals.

The Nigeria International Book Fair was the third player in the conspiracy. For it was the chief reason I left Iseyin a couple of days earlier than expected. Armed with a list of books and dozens of WhatsApp images of shea butter and Ankara fabric my friends expected me to take back home,

I set forth for Lagos hoping to, among other things, catch the literary discourses at the Book Fair. Even then, I was still oblivious to the fact that in less than two days, my bucket list would get two new blue ticks.

“He says you may pass by his office tomorrow in the morning and say hello. You are lucky because he is stuck in town, planning the Lagos@50 celebrations.” Those were the words Ebedi Patron Dr Wale Okediran, spoken to me after his telephone conversation with the Nigerian writer who has stayed longest in my memory and fancy.

That night, in my hotel room near the University of Lagos, I recalled how, months earlier, I had read an article about Soyinka’s plan to tear up his green card and leave the USA. I then wondered if, perhaps, I had Trump to thank for my good fortune. I’d also mulled over what to take to the professor, and what to talk to him about. After three futile attempts at scribbling him a poem, I carefully unpacked my pink suitcase, got out the only ‘Kenyan’ gift I could find, a copy of Kwani? 5, then dedicated it to him.

STARTED WITH A TELEPHONE CONVERSATION

Inevitably, our encounter was to start with a telephone conversation during which an anxious voice, hard to recognise as my own, informed Soyinka that I’d be at his office at 11am. I didn’t tell him yet, that a friend and fellow 2016 Writivism Short Story prize short listee, Joe Aito, on a flight from Port Harcourt, would be coming along.

Dr Livingstone, I presume? The famous greeting, pronounced by Henry Morton Stanley upon finally locating Dr David Livingstone on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, came to mind as I walked the width of Soyinka’s office and settled in on a wooden straight back chair.

For me, though, there was no need to presume. For I had met the man in the white Afro halo before, thanks to grainy old photographs. As a young man with a black Afro and the first two shirt buttons open; in the yellowing pages of old books while being arrested by a policeman and as a young revolutionary poet between the covers of Conversations with African Writers, a collection of interviews conducted by Robert Serumaga and Lewis Nkosi.

“Sir, thanks for the books you have written and for being such an outspoken writer and critic, I really enjoyed reading your childhood memoir Ake.”

That is was how I had imagined starting off our conversation.

“Sir, my dad said to tell you he studied The Lion and the Jewel in his A-level and he loves your writing, my granddad taught your books, too,” was the weak, barely audible stream of words that left my mouth.

Joe then joined us and the three of us sat and talked about a myriad of issues ranging from the staging of Fela the Musical during Lagos at 50 celebration to the challenges facing writing residencies and about Port Harcourt — the UNESCO world book capital.

It was after he had autographed the books we had brought along that we suggested to Professor that we should take a selfie with him.

“I don’t take selfies, not at all. In fact, I have placed an embargo on taking my pictures. However, I’ll make an exception, because you are an Ebedi writer,” he said.

I neither got to ask him the questions on the list I had prepared nor about his daily schedule. I never even got to express my surprise at the discovery that Fela Kuti, the Nigerian pioneer of afrobeat music, was his first cousin.

Yet as I stepped back to the noisy world of danfos and agege bread hawkers, I knew that in Prof’s final declaration of ‘no selfie’ lay the noteworthy takeaway I needed. That a writer’s duty is not to navel-gaze but to also engage with, question and speak up against the evils he sees in society. For as Achebe asserts in his memoir There Was a Country; in writing there is a moral obligation.

Gloria Mwaniga is a teacher based in Baringo County