In face of terror and betrayal, resilience will get you back up

She retraces the diplomatic steps that led her to her first posting as ambassador, with Nairobi as her first station. PHOTO| JEFF ANGOTE

What you need to know:

- Ms Bushnell's book is more than a lament, however.

- She retraces the diplomatic steps that led her to her first posting as ambassador, with Nairobi as her first station, although she had worked in the Africa Bureau of the US Foreign Office, where her team had taken care of a head of state who had been deposed.

Global terrorism has spawned a new genre of writing, mainly memoirs of survivors and tales of resilience by those who have lived through an attack or have been involved in rescue efforts.

In Kenya, one of the better known books that take a look at global terrorism is “14 Cows for America”, written by Carmen Agra Deedy.

This is the illustrated biography of Wilson Kimeli Naiyomah and how he was moved by the September 11, 2001 attack on the twin towers in New York and other targets in Washington DC.

Seeing the pain that the attack left in the hearts of the American people, Kimeli, who was living in the US, returned to his roots among the Maasai and beseeched the elders to do something to help ease the pain the Americans were going through.

That was when they decided to offer 14 cows as a way of expressing their commiseration.

Another biography of a Kenyan, Dare to Defy, The story of Peter ole Shompole, published by Santuri Media last year, also makes passing reference to this incident.

In the book, Mr Shompole writes: "When some terrorists struck some parts of the United States on September 11, 2001, the outpouring of grief and commiseration with Americans was overwhelming.

As a Kenyan man who had experienced first-hand the disruption of violence wrought by the Mau Mau freedom struggle, I was as shocked as the rest of the world and that motivated me to travel from Kenya to America to visit my relatives."

JOLTS AND UNITES HUMANITY

His words bring to the fore both how terrorism jolts as well as unites humanity and the contradiction that although by its very nature, terrorism aims at spreading fear, it ends up firing up the courage of its targets, in the process energising humanity to rally in defiance, hope and courage.

Now, a former US ambassador to Kenya, Ms Prudence Bushnell, has added her story to the growing body of works about personal resilience and victory in the face of terrorism. Ms Bushnell was meeting the then Commerce minister Joseph Kamotho in her Nairobi office on the morning of August 7, 1998, when a bomb went off at the entrance of the building that housed the embassy.

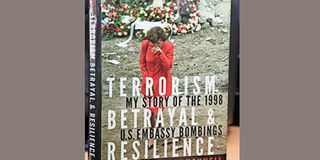

"The building swayed; a teacup began rattling; shards of glass and ceiling tile sprayed the area. One thought swirled dreamily around my brain as every muscle in my body clenched in revolt. "I am going to die." I was on the top floor of a high-rise office building that I knew was going to collapse," Ms Bushnell writes in the opening paragraph of her book, “Terrorism, Betrayal & Resilience”. The book, which is soon set to hit the Kenyan market, was published by Potomac Books in 2018.

This, however, is not just a story of Bushnell's lucky escape. It is also an indictment of the indecision by government officianados who are indifferent to the cries of their subordinates and how this indifference exposes "innocent bystanders" to terrorist attacks, often with devastating consequences for individuals, communities and nations.

Ms Bushnell laments that she had on many occasions alerted her bosses in Washington DC that the location of the embassy across the road from the Nairobi railway station and the busy Haile Selassie bus stop and roundabout, increased the risks of a terrorist attack on the installation.

However, her cables to America went unheeded until the attack that claimed 254 lives and left more than 5,000 others injured.

The attack, 21 years ago, remains the worst in the history of Kenya.

The former ambassador also voices her dismay at the misplaced priorities of leaders during times of great humanitarian crises.

She says that hours after surviving the attack, she received a call from the then US Secretary of State, Ms Madeleine Albright. She told Ms Albright that she had sent messages after messages to the Foreign Office, expressing her fears of a terrorist attack, but nothing had been done about them.

"I never got them," she quotes Ms Albright as saying.

Soon after, Ms Bushnell received a call from the then US President Bill Clinton. All Mr Clinton wanted was for Ms Bushnell "to secure the perimeter" of the embassy building. She writes: "What? Really? I could hardly believe my ears. Where was the famous 'I feel your pain'? We could have used a little of that."

On that day, however, she would not get to hear the comforting words from her bosses in Washington. Instead, Mr Clinton said: "hold on a second … and you need to secure the perimeter of the building next door too."

It did not matter to Mr Clinton that rescue efforts were ongoing, that people were still pulling survivors and victims from the rubble and that a sea of humanity had gathered in the area, not just to witness but also to help.

Neither did it matter that by the time he was giving the instructions, what he wanted done had already been done.

Ms Bushnell's book is more than a lament, however. She retraces the diplomatic steps that led her to her first posting as ambassador, with Nairobi as her first station, although she had worked in the Africa Bureau of the US Foreign Office, where her team had taken care of a head of state who had been deposed. She had also been caught up in the red tape and the US policy of non-interference that delayed humanitarian intervention during the 1994 Rwanda genocide. More than 800,000 people were killed in the three months of the ethnic violence.

This notwithstanding, it is what happened during and after the August 8 bombing that takes up the bulk of Ms Bushnell's book. She recalls how hope turned to anger when US soldiers gave preference to their countrymen and women during the rescue operation and how Opposition leaders felt jilted when Ms Albright flew to Kenya and could not meet them because of a tight schedule caused by a flight mishap. In the eyes of the Opposition, Ms Albright had added salt to the wounds inflicted by the terrorist attack.

But worse was awaiting Ms Bushnell. When the FBI director, Louis Freeh, landed soon after Ms Albright had left, he gave Ms Bushnell a stark choice. He had a plane waiting and it had only a few vacant seats.

"Select people you want to take those seats — unless the Department of State has made other plans for you," he told the ambassador. The plan was that bombing of terrorist bases in Sudan would start after that plane had safely crossed the Sudan airspace. All that Ms Bushnell could do was wish the FBI boss a safe journey. There was no way she was going to leave Nairobi.

"The next day, as missiles flew into a pharmaceutical plant in Sudan and an al-Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan, the department warned US citizens around the world to take care. We closed the embassy and American schools at noon and waited to see what would happen," writes Ms Bushnell, who has since retired from diplomatic service and is now the founder of the Levitt Leadership Institute at Hamilton College in New York.

She writes that one of the biggest lessons she has learnt in life was the importance of a leader taking care of his or her people.

"This advice, from a former boss and mentor at the Foreign Service Institute, popped into my head 24 hours after the (1998) attack. It became my mantra and leadership philosophy." And this explains why she did not quit even when she was offered a chance to ship out as the US embassy smouldered after the attack by Osama bin Laden's jihadists.

BUSHNELL IN HER OWN WORDS

There were individual funerals. Americans and Kenyans went in mixed pairs to represent the embassy, often going great distances.

It took a toll on an already exhausted and traumatised community, and it was the right thing to do.

Two hundred and one funerals took place, but as a nation, Kenya mourned the death of Rose Wanjiku most publicly. She had survived under the Ufundi House rubble for more than four days.

She became a national symbol of hope, “the Kenyan Rose.” When she died, hope turned to anger.

Besides the dead, 400 people were severely disabled, and 164 more had acute bone and muscle injuries.

Thirty-eight others were blinded and fifteen totally deafened; seventy-five more suffered from severely impaired vision; and forty-nine were living with hearing disabilities. Hundreds of businesses