Jane p’Bitek: Filling my dad’s shoes is an impossible task

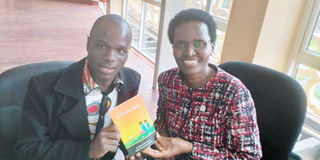

Writer Oumah Otienoh with Ugandan author Jane p'Bitek, daughter of Okot p'Bitek, at the Uganda National Cultural Centre in Kampala in November 2019.

What you need to know:

Mzee was so big. It’ll be sacrilegious to compete with his writings. In fact, I write under his towering literary shadows.

I usually besiege people to critique my works separately and not to tug his name along.

I’m working on a second anthology of poems and it will again follow the Song School.

Jane Okot p’Bitek is the daughter of the renowned poet Okot p’Bitek. She is a lawyer, a fellow of the Institute of Chartered Secretaries and Administrators (ICSA) and holds an MBA in entrepreneurship and business venturing from the University of Stirling, Scotland.

She was a part-time lecturer at the Law Development Centre and is currently the Deputy Registrar-General (Registries) with the Uganda Registration Services Bureau.

She is an author of Song of Farewell (1994) and a co-author of A Poetic Duet (2016) — both anthologies of poems.

She spoke to the Saturday Nation at the Uganda National Cultural Centre about being a poet and how her legendary father transformed her worldview.

How has it been for you with a tag of the legendary Okot p’Bitek as your father?

The name p’Bitek has been huge and a door-opener up to date. Upon finishing Senior Six, it was a requirement that the District Commissioner approves of your documents before proceeding to university. When I walked into his office in Kampala, he felt elated that I was Okot p’Bitek’s daughter and quickly signed my documents. Everywhere I introduce myself, people always marvel.

Still on the epic name, has it been more of a blessing or a curse to you?

It has been a big blessing. More so, as a poet, I’ve enjoyed tremendous approvals from many readers across East Africa and beyond. On the contrary, I also get a lot of pressure from associates who expect me to measure up to my dad’s writings, which is an enormous task.

Did he in any way influence your writing of 'Song of Farewell', which has his flesh in it?

He partly influenced the writing of Song of Farewell as he read and corrected the original manuscript and would take my poems for publication in the mainstream newspapers. I picked the tittle “Song” and wrote the anthology of poems. Many literary pundits thought that I adopted my father’s style of writing and that’s why the label “song”. I began penning Song of Farewell way back when I was in high school.

Looking at the Song school, do you think that your dad eclipsed your writings as his prolific works such as 'Wer pa Lawino' and 'Wer pa Ocol' remain popular across the continent?

Mzee was so big. It’ll be sacrilegious to compete with his writings. In fact, I write under his towering literary shadows. I usually besiege people to critique my works separately and not to tug his name along. I’m working on a second anthology of poems and it will again follow the Song School.

In the epic 'Wer pa Lawino', do you agree with the lead character, Lawino, that all that is black is beautiful?

Black is beautiful. We have our culture as Africans and it shouldn’t be subjugated by the western influence. This is what influenced Song of Farewell, which is so rich in the African culture. On the flip side, I will advocate for a mix of the two cultures, thus partly defending Lawino.

Okot p’Bitek’s 'Wer pa Malaya' has been labelled lewd by some literary pundits. How did this go down with your family?

Interestingly, Wer pa Lawino and Wer pa Ocol eclipsed it. We never talked much about this song as a family. It’s true that p’Bitek never “dressed” the song as I did in Song of Farewell, which also mentions a malaya (a prostitute). P’Bitek was blunt and thus didn’t mind the language he used in his works and that’s why the song is unpopular with our schools.

And talking of p’Bitek’s family, your other siblings — Julliane Bitek and George p’Bitek — are hardly visible on the literary scene. Didn’t your dad’s great writings spur them to write?

We were born seven in our family, though we lost one of us. Three of us — Julliane, George and I — went the art route while the rest are scientists. Julliane may not be well known at home (Uganda), as she is based in Canada, but she is a great pen-woman. Sometime back she visited the country when she did a paperback, 100 Days, a book that talks about the gruesome 1994 Rwandese genocide. Maybe if she was here, her works would be in our syllabus.

George has some huge talent in writing. I read most of his works when he was a schoolteacher. Even so, he got more absorbed in business than writing.

Lastly, for me I balance between writing and my career as a civil servant. I’ll fully plunge into writing next year as I’ll be exiting the civil service.

In the poem anthology 'A Poetic Duet' that you co-authored with Sophie Bamwoyeraki, ‘The Arrested Ministers Repentant Plea’ makes one jeer at the selfishness of public servants. Is this the norm in Uganda?

Corruption in most African countries is a way of life. When you fight it at the workplace, you become an enemy of the people.

Still on the anthology, ‘For Better, For Worse’ stands out as one of the best crafted poems. Is it tell-tale sign of failed marriages in Uganda?

It’s always amazing the extravaganza for newly married couples and hardly three months later, they are separated. My advice to couples is, have valid reasons for tying the knot. Don’t date one because of the riches but out of love which should be a long-lasting affair. Can you believe it? I started dating in campus and I’ve now lived with my significant other for close to three decades.

P’Bitek was a close associate of other prolific Ugandan penmen such as Okello Oculi, John Ruganda and David Rubadiri. Did you ever interact with these iconic writers?

I hardly remember Okello Oculi, but he used to visit our home in Uganda. As for John Ruganda, he was a regular guest at home. My dad was so close to David Rubadiri and when both were exiled, Rubadiri hardly left our Nairobi house.

You initially preferred to study sciences instead of liberal arts, which was your dad’s forte. Why couldn’t you pick the liberal arts as your first option?

I wanted to know people as a teenager and I thought that the only way out was by studying medicine. My high school headteacher, an Irish woman, insisted that if I opted for the sciences, I’ll have to exit the school. I stayed put as my dad could not entertain me exiting the top school.

Song of Lawino and Song of Ocol have never left most African classrooms, including my home country Kenya. Do you swim in affluence from book royalties?

This is the headache with writing; the writer is mostly slapped with some meagre book royalties. Truth be told, the publishers are never fair with writers. You’re sometimes forced to beg for your dues in order for something to hit your bank account. My mum always advised me never to leave my daytime job for full-time writing.

Your parting shot to budding writers?

It’s good to write. Let’s pacify Taban Lo Liyong’s aphorism that East Africa is still a literary desert. Through writing, we are also certain of preserving our culture. I’ll also advice upcoming writers to be voracious readers as with wide reading, your storytelling skills are honed.

The writer teaches at Ng’iya Girls High School in Siaya County and is a regular contributor on literary issues in the ‘Saturday Nation’. He is the secretary at the International African Writers Association (IAWA) based in Abuja-Nigeria. [email protected]