Jomo Kenyatta’s five crucial lessons in educating a Kenyan

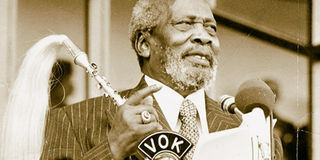

President Jomo Kenyatta. His book ‘Facing Mount Kenya’ contains solutions to the problems bedevilling our education sector. PHOTO| FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- This is why in this period of remembering Jomo Kenyatta, I think we could look at the six lessons or stages of educating a Gikuyu child, as he spells it out in Facing Mount Kenya.

- These are lessons that can be found in several, if not all other Kenyan communities.

The one disturbing thing about our system of education is that it is so pegged on foreign models that when it suffers shocks, as it is experiencing today, we are at a total loss on what to do. We can hardly say that our curricula draws any inspiration from our cultures, histories, spirituality, thinking, or everyday life. We have borrowed so much from the rest of the world without tampering it with some local pedagogy.

If there is anything in our syllabi, it is very basic, kind of ‘traditional’, as we like saying. Yet, we could have made a wonderful mukimo of an education system if we had bothered to borrow ingredients from our cultures, histories and philosophies.

This is why in this period of remembering Jomo Kenyatta, I think we could look at the six lessons or stages of educating a Gikuyu child, as he spells it out in Facing Mount Kenya. These are lessons that can be found in several, if not all other Kenyan communities.

They are worth imbibing. Maybe parents out there, or schools and those who run the education system could just insist that this book be a compulsory reading in the new curriculum, especially at secondary school level.

Lesson one is in infancy. Mother and nurse are key here. But lullabies are the method of education. Sing to the child. Soothe their emotions. This way, the people’s history will be passed on to the child, so says Jomo. When the child begins to speak, the mother has to teach it speech mannerisms, names of family members, past and present, Jomo writes.

Again, sing to the child and let the child imitate the adults. Don’t instruct. Then when the child can speak, Jomo instructs, ask them questions about such as: who is your father? What is the name of your grandfather? Why were they given such-and-such name…?

Lesson two is during childhood. Teach the child how to sit and walk properly, according to Jomo. In fact he says this will help them to avoid ‘developing bow legs.’

Continue with the songs but also introduce games. This creates a sense of freedom and fair competition but also helps the child to develop. The father has to train the boy in practical activities such as farming, or should we say repairing things around the house these days. But the child should also be trained to observe the environment and how to manage it.

The mother should take care that the daughter is taught about domestic duties. Jomo says that the mother, though, is in charge of co-education of the boys and girls. So, if we hope to bring up good citizens, the mother’s wisdom and teaching skills are key here.

Lesson three is when maturity arrives. We can dispense with Jomo’s advice about piercing of the ear, and maybe live with the circumcision. The initiation ceremonies at this stage bound the individual to the philosophies, beliefs, traditions and lifestyles of the community. But the point is that a young man or woman — and adult to be — is now responsible for their actions and can be punished when they err.

There is no unfettered freedom just because one is no longer a child. As a man or a woman, one’s freedoms are bounded by those of the community and one may be called upon to serve the society at any time, as a warrior, professional, caregiver etc.

Marriage is key in the education of the individual, Jomo advises. This, he says, is a superior status, in the ladder of education, and has its corresponding rights and duties.

A married person is responsible for the lives of the child that they will bring into the world. This person partakes in all ceremonies and rituals of the community and may contribute to the decisions on the welfare and future of the society.

The last lesson is the general one. This is about everyday life. Respect and duty to parents is fundamental, Jomo insists. Social obligations must be taught and emphasised, especially to age mates.

The spirit of kinship has to be cultivated. Relatives are real and they do count, especially when one is in need. This is why Jomo’s last words on the education of an African child is: “In the Gikuyu (insert here any other community) community there is no really individual affair, for everything has amoral and social reference.

The habit of corporate effort is but the other side of corporate ownership; and corporate responsibility is illustrated in corporate work no less than in corporate sacrifice and prayer.”

Read Jomo Kenyatta’s Facing Mount Kenya, again, if you are worried about the body corporate called Kenya.

The writer teaches at the University of Nairobi. [email protected]