Just as you had your own jig in Japan, allow us our dance

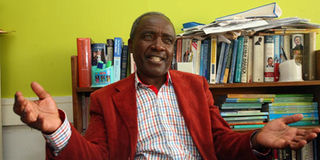

Prof Henry Indangasi teaches literature at the University of Nairobi. PHOTO | EVANS HABIL

What you need to know:

- The gall cut deep because this architect’s complaints meant one thing: Some of Kenya’s oldest and top literary dons were arguing from their powerful positions on the strength of inadequate knowledge.

- Might we have home-grown alternatives and how can he access them was the last sincere request.

- The implication was that home-based Kenyan literary dons had little or nothing of value to show the world by way of knowledge production.

A Kenyan architect practising in western Europe emailed me to complain that “you compatriots are doing the wrong things with postmodernism” in the ongoing literary debates.

He was responding to the March 17 article titled ‘The banal, the false and the half true in dons’ diatribes’. As if I was the author, he wondered why dons were busy “peddling lies on the intellectual movement” that had served him so well in his architectural studies and practice.

After explaining that my name had been mistakenly planted at the end of the article and that I was not a captive of any theory including postmodernism, he sent another email to insist that we should respect a way of thinking that is a “potpourri of methods and theories for understanding and critiquing design, dance, music, film, architecture, culture, literature, art, drama and many more”. I also assured him the author was a postmodernist performer of sorts as I would show later.

He further observed that we were mixing up issues and that the essay titled ‘The death of the author’ is a celebration of a fixed structure and not postmodernist as claimed in an earlier write up by one of the dons. As if teaching a novice, he argued that the essay celebrated the power of good writing and language use whose self-sufficiency literally renders the author irrelevant. He appropriately likened the “dead” writer to himself as an architect nobody bothers about after the completion of a building he designed from sketches and “numerous disorders”.

Perhaps the most embarrassing part of the email was the query about my age and others’. Postcolonial and postmodern discourses were so old that we must have been particularly young to be arguing about them so many decades late. Associating them with glibness, intellectual fraud and trickery was, for him, an “inexcusable devaluation” of his degree.

The gall cut deep because this architect’s complaints meant one thing: Some of Kenya’s oldest and top literary dons were arguing from their powerful positions on the strength of inadequate knowledge. Might we have homegrown alternatives and how can he access them was the last sincere request. The implication was that home-based Kenyan literary dons had little or nothing of value to show the world by way of knowledge production.

A further implication is that University of Nairobi’s Department of Literature, the mother of literature departments in most Kenyan public universities, had failed in scholarship. If one did a historical study of the department one may find out why even the non-literati doubt its achievements and value.

I am unable to respond to what are called “pseudo-profundities of post-colonialism” because the article does not provide the profundities (unless I am not attentive enough|).

Nor need I delve into the sideshow on how I met and chatted with Prof Andrew Gurr many times in 1972/73 in my cousin’s house on Rose Avenue or Close where they were interacting as neighbours.

What Gurr said or did in literary terms matters more than how long I met him.

The article on banalities and falsehoods by dons duly refers to a literary revolution it says never was but whose child I am. I must confess that I imbibed many practical approaches to literary study and therefore related very easily and cosily to the literary goings-on in Kenya and beyond.

The theories and methods were dubbed Marxist because they mainly questioned the inhumanity of capitalist imperialism and neo-colonialism.

That’s why Ngugi wa Thiongo’s intellectual activities as head of department and prolific creative writer led to his detention without trial and eventual dismissal from the university.

What happened thereafter and why his revolution died is the big question.

Many other heads of department followed as the government of the day cracked the whip on academics and ruthlessly curtailed their real or perceived anti-establishment political activities. The longest serving head, however, was Prof Henry Indangasi. It must have been some fifteen years but I stand to be corrected.

GOOD ENGLISH

All I know is that he definitely had many more years than Ngugi to make a mark. I dare say he had enough time to revert to the old Department of English and ensure teachers were trained to teach good English. He needn’t blame me or Prof Evan Mwangi because he was long enough at the helm to make a difference to the standards of English in the country.

My conclusion may be wrong but I think Prof Indangasi’s reign was a counter-revolution that remains in gestation. For if he had successfully “de-Nguginised” the departments, as some refer to his reign, then we would not be worrying about how to adhere to good English writing rules.

Being a patriotic Kenyan like the professor, I am obviously concerned that we should all speak and write good intelligible English.

Yet like all democratic compatriots, I don’t like being terrorised into being preoccupied with the teaching and writing of grammatically correct compositions or essays within a constricted ideological space in which the free flow of theories and ideas is literally banned.

I don’t want to go to the extremes of another colleague who calls it “condemning free thinking to the Siberian freezer”.

Thus when the article observes that we have an “underperforming” academic class, in Kenya, the author need not gloss over his adverse contribution.

As for “unserviceable theories” he doesn’t like, I think he is as postmodern as can be in Japan.

'NOT A GREAT DANCER'

By presenting a Luhya wedding song in Japan, the professor is deep into the particularistic and demonstrates that each artistic piece deserves its space, a hearing and dignity on earth. On his own confession that he is not a great dancer and singer but performs all the same, he is admitting that nobody has a monopoly of style and every kind of jig including merely nodding the head is acceptable in a postmodern world.

He treats the reader to a medley of oral literature, music, dance, philosophy etc and therefore eliminates territorial boundaries a stylistician may be professionally tempted to draw even as he wallows in the depths of a postmodern cauldron in Japan.

The nuanced wedding performance firmly belongs to humanity’s postmodern condition.

Finally, let us echo Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God. There we are told that a good dancer must keep moving from one spot to another.

He must not hit his heels against one spot forever. My not-so-profound undergraduate interpretation of this very long ago was that if one dances on one spot only one may break the ground and eventually bury oneself without reproducing. I called it the dance of death.

Thus as we do professor’s bidding that we write good English we must be careful not to suffocate ourselves in the stylistics and beauty of Queen’s English at the expense of Kenyan English because that shall have stunted the essential need to move and produce usable knowledge for changing Kenyan generations.

To paraphrase and use Ezeulu again but out of context in Arrow of God, I am a mere mortal and cannot do what is done by the gods of knowledge.

I therefore root for the freedom to deploy and utilise ideas and theories as they come down from the gods and not remain static in one way of doing things. In a way, the god of postmodernism landed on professor in Japan and made him perform from a very complex Kenyan script full of organised chaos.

Understandably, he didn’t know because the spiritual comes to all of us unseen, unknown and in mysterious ways. Thus even gods know a thing or two about the postmodern.

Amuka is a professor of literature at Moi University.