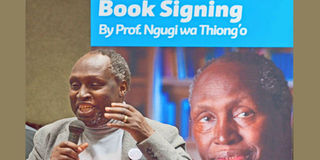

Celebrating Ngugi at 80: Kenyan scholars pen book on literary artist

Celebrated author, playwright and critic Ngugi wa Thiong'o on June 13, 2015. PHOTO | FILE | AFP

What you need to know:

- Ngugi is the foremost East African literary artist and a globally respected thinker.

A newly released book by Simon Gikandi and Ndirangu Wachanga includes reflections with critical engagement on Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s writing, activism, and theoretical positions.Ngugi: Reflections on his Life and Writing brings together a wide variety of short meditations on Ngugi’s multi-faceted creative and theoretical work to celebrate the author’s 80th birthday.

Born on January 5, 1938, Ngugi is the foremost East African literary artist and a globally respected thinker. Indeed, when the Nobel Committee asks for nominations this year, I’ll for the first time tell them: Ngugitosha. The Kenyan author has in the last decade or so been perennially favoured to bag the Nobel Prize in literature.

Ngugi is a distinguished professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine.

The editors are also eminent scholars. Gikandi is the Robert Schirmer Professor and Chair of English at Princeton University and the president of Modern Languages Association, the most prestigious literary studies body in the US. Prof Wachanga teaches Media Studies and Information Science at the University of Wisconsin and is the authorised documentary biographer of Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Ali Mazrui, and Micere Githae Mugo.

The book is published in Britain and the US by James Currey. The respected contributors in the volume know Ngugi in person and use the opportunity the book offers to bring to the fore the most salient contributions Ngugi has made in literary studies and East African cultural production.

RIVETING

The book contains some short essays and poems by Ngugi, the most riveting of which is a tribute in Kiswahili to the Kenyan Marxist critic Grant Kamenju. I have for many years tried to profile for these pages the self-effacing Prof Kamenju, who once worked with Walter Rodney at the University of Dar es Salaam, but my contacts in the Kamenju family also prefer a low profile for him.

“Hakuna hata wakati mmojaambapo Kamenju aliwania kutaka kupata sifa,” (At no time did Kamenju ever seek fame), writes Ngugi in the essay first read as a speech at the University of Dar es Salaam in 2013. Kamenju preferred to engage with ideas and to pass on knowledge to his interlocutors, not publish essays and books to include as lines on his“Wasifu-Kazi” (CV) as other intellectuals would, especially those working in neo-liberal universities.

I have never met Ngugi in person. The closest I came closest to him was at the Goethe Institut, Nairobi, several years ago as he launchedRe-Membering Africa, one of his volume of essay. I avoid contact with big people.

But I have admired his writing. When I tried to teach his books at the University of Nairobi in the late 1990s, the students went behind my back to report to the head of the department that I was teaching them bad books. Today, whenever I am in a Kenyan university, I make sure I am heard saying NgugiJuu! (Ngugi is great!) — just to irritate the Kanu-era professors who hate Ngugi for no apparent reason. NgugiJuu! Juu! Zaidi!

Gikandi and Wachanga’s volume is full of fond recollections of working with Ngugi. Sultan Somjee remembers his experiences at Ngugi’s Kamiriithu experience, in which villagers collaborated with Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Ngugi wa Mirii to produce one of the most powerful theatrical productions in East Africa. He credits the experience for the methodologies he later adopted in the study of Kenyan material culture.

“The evocative songs and music that spoke to the heart, the patriot in oneself, madeNgaahika Ndeendaimmediate,” writes Dr Somjee. “This was different from what was imparted in foreign tongues and art forms divulging appreciation of unfamiliar aesthetics and values that we received as students of art and literature.”

Grant Farred, the eminent literary scholar at Cornell University in the US remembers reading Ngugi’sA Grain of Wheat at the University of Western Cape in South Africa. The novel is one of the works that spurred him to read other African literary texts. He has no regrets that he abandoned his ambitions to become a lawyer, to specialise in the best that has been said and written about Africa by authors such as Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

Prof Kimani Njogu gives an account of the establishment of the Kikuyu-language Mutiiri journal at Yale University in 1994. “In imagining the journal, we sought to create a platform for cultural sharing and linguistic engineering.” For his part, Prof Alamin Mazrui notes that Ali Mazrui would have preferred the journal to be a bilingual periodical in Kikuyu and Kiswahili.

LESSONS AND DISCOVERIES

The poetry in the collection is evocative. Micere Githae Mugo’s poem in praise of Ngugi’s work and life imitates African oral literature.“Guku ni kwau?”(Whose home is this?) she asks in the voice of an African traditional dancer who also comments on her own technique. She does not stampede to the stage like an explosive “njau ya mbogo” (calf buffalo) like the griots she borrows from; rather, she claims the heritage of an intellectual who can tell a Pan-Africanist Kenyan with a thinking brain if she sees one.

To Micere, Ngugi embodies Kenya and Africa at large: “Hongera to the annual winner of the Nobel Prize of the heart/ Shangwe na vigelegelefor a beloved Kenyan and African son of the soil/ … Fivengemi for Ngugi, child of Wanjiku: Ngugi, son of Thiong’o!”

I will have to wait for the English translation of Ngugi’s new bookKenda Muyuru(Perfect Nine), as I have forgotten the little Kikuyu I knew:aterere.

Ngugi’s editor at East African Educational Publishers, Kiarie Kamau, has a Kikuyu essay in the book,Gucokia Rui Mukaro,which I have had to read in English translation (“Directing the River Back to its Course”), since I have now said farewell toaterere, anything to do with Kikuyu language and culture until they make me the Jean Veneuse Professor of Contemporary Ideas at the American university where I teach.

Seriously though, unlike Ngugi, I don’t think Kikuyu language can decolonise anybody’s mind, so I’ve chosen neither to speak it nor read anything in it for the next 10 years. The river can go back to its “mukaro” (course) after that. But for now, I don’t want to hear lies about how speaking Kikuyu will improve my life.

Not everyone agrees with me. Micere Githae Mugo and Alamin Mazrui appreciate Ngugi for writing in his mother tongue.

Other contributors in this beautiful volume include Eddah Gachukia, James Ogude, Grace Musila, the late Ime Ikiddeh, Charles Cantalupo, Tsitsi Jaji, Margaretta wa Gacheru, Carol Boyce Davies, Henry Chakava, Chege Githiora, and Susan Kiguli.

It is in this volume that I learnt that Cabral Pinto is former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga’s pen name. Under this name, Mutunga penned essays for theNation in support of human rights — including gay rights. It is in this context that I am no longer angry with Mutunga for telling his job vetting panel: “I am not gay!” as if there is anything wrong in being that. Now I’m convinced Mutunga had said: “I am not Ngei,” whom he surely was not.

Elsewhere, younger writers, such as Clifton Gachagua, imagine Ngugi in their poems as an embodiment of a rigid past, antithetical to the present queer times. But Ngugi is the queerest of all Kenyan writers, as he is the one who inMurogi wa Kagogo(Wizard of the Crow) reminds us against stereotypes surrounding Africanngwiko njogomu (queer sex).

***

I can’t thank my dog Sigmund enough for using his connections in high places to get me appointed an editor at theVasco da Gama Journal of Non-Existent Research.

Let politicians who have received PhDs without publishing any of their research papers as required by the Commission for University Education send their stuff to me for consideration. My charges are modest.

Dr Evan Mwangi teaches literature in the US. [email protected]