Likimani’s latest book is a tale of modern slavery

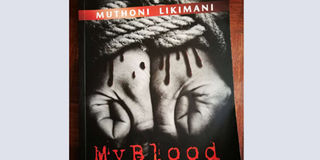

Muthoni Likimani’s latest book, My Blood Not for Sale, is a blistering indictment of the scourge of human trafficking in modern times. PHOTO| FILE| NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Muthoni Likimani, aged over 92, is arguably the living matriarch of Kenyan literature who has defied age to publish yet another text.

- Born in Murang’a in Central Kenya in 1926, she was the first Miss Kenya who studied in London and worked as a broadcast journalist for the then Voice of Kenya and the BBC.

Muthoni Likimani’s latest book, My Blood Not for Sale, is a blistering indictment of the scourge of human trafficking in modern times.

It evokes feelings of horror at the various manifestations of modern slavery, which essentially re-enacts the heart-wrenching ordeal that Sarah Baarman underwent in the 19th century.

The story of the Southern African woman Sarah Baartman, exported to Europe for public display, is one of the most horrendous instances of human trafficking.

The sad story typifies the perpetual victimhood of people of African descent from antiquity to modernity. Sarah Baartman, of Khoikhoi or Hottentot

origin, was lured with false promises of prosperity and plucked from her ancestral home in South Africa in 1810 and shipped to England, where she

was put on display in freak shows. Why? Her physical features piqued the European gaze and earned her the tag Hottentont Venus, because in the

European imagination, she was very unlike the women of the civilised Western world. She was displayed on stage in a cage in shows that earned her

European captors a colossal amount of money.

She was a slave. All efforts to have her released from the hands of her inhuman and inhumane captors fell flat. She would later be moved to France,

where she was made an object of medical and scientific research to satiate a curious European fascination with African female sexuality.

But the Hottentot Venus remained a slave in life and death as well. Upon her death, her genitalia, skeleton and brain were put on display in a museum

in Paris until 1974.

Muthoni Likimani, aged over 92, is arguably the living matriarch of Kenyan literature who has defied age to publish yet another text. Born in Murang’a

in Central Kenya in 1926, she was the first Miss Kenya who studied in London and worked as a broadcast journalist for the then Voice of Kenya and

the BBC.

WRITTEN PROFUSELY

She has written profusely over the years. Her literary output includes They Shall be Chastised, What Does a Man Want? Fighting Without Ceasing,

Passport Number F.47927: Women and Mau Mau in Kenya and The Magic Bird and the Millet Farmer.

In a recent conversation, she assured me that more of her texts were on the way. What a remarkable spirit of longevity and creativity.

In an earlier interview with Emeka-Mayaka Gekara and Julius Sigei, published on June 28, 2013 in the Saturday Nation, Muthoni had pointed out that

she was working on the book under review, which she characterised as “politically explosive.” She has faithfully kept her promise.

Indeed, it is a book with a series of fictional accounts of cases of human trafficking with a consistent acerbic critique of modern slavery in post-independence Kenya. Audacious and unapologetic authorial comments appear again and again to condemn modern slavery. In a sense, the book is an

impassioned and unequivocal appeal to all and sundry to fight modern slavery in all its forms.

Throughout the book, the author points to the irony of the re-immergence of human trafficking after the egregious slave trade and colonial rule had

officially and ostensibly ended.

As the multiple stories in the book illustrate, human trafficking comes in the form of men and women duped into going for greener pastures in Europe

or the Arab world only to be turned into objects of unspeakable cruelty in general or into sex slaves in particular, or international and local criminal

cartels that steal babies and children across borders or kidnap unsuspecting school-going children, or parents who peddle their offspring to strangers

for the dollar.

The consequences of these acts of inhumanity, she demonstrates, include incurable emotional and physical wounds or trauma, financial loss and

sometimes even death of the victims. In this regard, even religion is not irreprehensible. My Blood Not for Sale castigates those who use religion as a

subterfuge for human trafficking, for instance, by falsely offering to pray for gullible childless couples to conceive, yet in reality they engage in dubious scheme of baby stealing and baby swapping.

She is particularly furious that flag independence in modern African states did not translate into real freedom, and the masses are prone to being victims of forces of modern slavery.

This, she repeatedly argues, both overtly and explicitly, runs against the grain of the great expectations of the masses of Africans liberated from conventional slavery and the ravages of the colonial encounter.

In sum, My Blood Not for Sale, written in a deceivingly simple, straight forward and conversational style, is a testament to the fact that we are not yet past the spectre of slavery despite our grandiose claim to the contrary. So long as we are still winking at or complicit in the vice of human trafficking, our claim to civilisation and modernity is mendacious and hollow.

This is yet another great gift from the living matriarch of Kenyan literature worth reading.