Instead of branding university courses as useless, Ruto should help create jobs

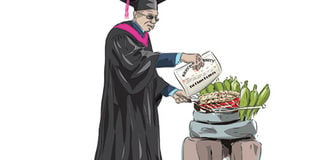

The fact that we have many graduates in the humanities, social sciences, and even the natural sciences who cannot find employment speaks volumes about those in charge of the economy and public policy. ILLUSTRATION | JOHN NYAGA

What you need to know:

- In the US, to graduate with a BA degree, one must take a certain minimum number of courses in the natural sciences and vice versa.

- A student graduating with a BSc in neuroscience would have also taken courses in the arts, humanities, and social sciences.

- Such graduates are so well-rounded and versatile that they easily find their niches in the post-graduation dispensation.

- This is the kind of education we need in our universities. The kind that opens up and expands our students’ minds with critical thinking skills and multiple interdisciplinary perspectives, thereby equipping them with the capacity to change their society and their world.

On Wednesday October 24, Deputy President William Ruto — who was my year-mate at the University of Nairobi where he studied Botany and Zoology at Chiromo while I studied Political Science and Linguistics at Main Campus — is reported to have dismissed anthropology and sociology as courses not worthy studying at the university.

To this list of “irrelevant” courses, he added history and geography. Urging universities that receive public funding to “up their game,” Ruto asserted that universities should be ashamed of churning out “unemployable” graduates who end up “roasting maize on the roadside.”

Unfortunately, this is not the first time Ruto is dismissing the humanities and social sciences as irrelevant to the Kenyan economy. He did the same back in 2010 when he served as minister for Higher Education.

But, is it really true that anthropology, geography, history, and sociology are irrelevant? Should universities exist primarily to serve the labour market? To take this position, as the deputy president does, is to portray a fundamental misunderstanding of the essence and role of a university in society.

FUNCTIONS

Universities as degree granting institutions were first established in Africa and Asia before they emerged in medieval Europe. Their purpose was to offer tuition primarily in non-vocational subjects; to train the mind in higher thinking.

To force universities to be primarily defined by their capacity to serve the economic labour market is to radically depart from the premise that universities exist to serve the general public rather than the narrow interests of capitalist entrepreneurs.

As the 1963 Robbins Report on Higher Education in the United Kingdom points out, universities are charged with four main functions of which instruction in skills is only one.

The other three are the search for truth (hence the importance of academic freedom), the transmission of a common culture and common standards of citizenship, and, most importantly perhaps, the promotion of the general powers of the mind in order to produce cultivated men and women rather than mere specialists and automata for the labour market.

How, pray, can universities achieve these functions without anthropology, sociology and history? We do not need fewer sociologists as Ruto suggests, but we need every student at university to study some sociology, history, geography, literature, philosophy, religion, etc.

Indeed, the discipline of sociology should be the course for all law enforcement officers as well as those in the criminal and civil justice realm. After all, sociology is the study of the development, structure, and functioning of human society.

You cannot effectively police society nor can you effectively dispense justice without a fundamental understanding of how the society works. No wonder in the United States, it is sociologists who train personnel for the criminal justice system.

HUMANITIES, SOCIAL SCIENCES ARE IMPORTANT

The fact that we have many graduates in the humanities, social sciences, and even the natural sciences who cannot find employment speaks volumes, not necessarily about those in charge of university education, but most squarely about those in charge of the economy and public policy of which Ruto is the deputy chief executive.

It is the role of government to implement policies that facilitate the growth and expansion of the economy to ensure employment for its citizens. Indeed, in mature democracies, high unemployment rates almost always lead to electoral loss on the part of incumbent governments.

The current unemployment rate in the United States is 4.0 per cent, the lowest in a decade. It was at its highest in 2010 at 10 per cent during which time the Democratic Party lost majorities in both houses of congress in the midterm elections of that year.

On the other hand, the unemployment rate in Kenya has remained in the double digits for the last decade and even beyond. It was at its lowest in the last decade in 2008 at 10.9 per cent. By the end of 2017, it stood at 11.5 per cent.

Unemployment rate in Kenya has remained above 11 per cent for the entire period that Ruto has been deputy president — catastrophic for incumbent political parties in industrial democracies, but not so in Kenya where Ruto’s party went on to “win” re-election in 2017 despite the high unemployment rate.

If indeed Kenya needs more electricians, masons, and machinists, as Ruto says, it still behoves the government to incentivise the training of such skilled manpower, ensure their employment, and remunerate them adequately.

In any event, is it not the government that wantonly converted tertiary diploma institutions that trained personnel in these vocations into degree-granting universities?

It is ironic that Ruto spoke on a day he is said to have defended his PhD thesis at the University of Nairobi. With a PhD in Plant Ecology, I challenge my undergraduate year-mate to return to the university classroom to help train the next generation of botanists if indeed he believes these are what the Kenyan economy needs. Otherwise the PhD would be wasted were he to choose to continue with his political career.

PRIORITIES

Given how we have our priorities upside down in Kenya, however, I doubt that Ruto is likely to abandon politics for the university lecturer’s mantle any time soon. We pay our politicians obscenely more than we pay our professionals.

In fact, Kenyan legislators are paid much more than their counterparts in industrial democracies. It is on account of this that all manner of Kenyan professionals, including engineers, lawyers, medical doctors, economists, accountants, pharmacists, journalists, and botanists, among others, hustle to remain in politics. That is where the money is.

What is true in what Ruto said is that our university education needs reform; but not the kind that Ruto recommends.

What is needed is to integrate the teaching of the multiple disciplines in the arts, humanities, natural sciences, and social sciences so as to produce well-rounded critical thinkers with the requisite versatility to be innovators, pacesetters, change agents, and job creators rather than just job seekers.

In the US, for instance, to graduate with a BA degree, one must take a certain minimum number of courses in the natural sciences and vice versa.

In the university where I teach, our curriculum is based on 12 foundations. Apart from fulfilling the general degree requirements, as well as requirements for a major, students must also fulfil the 12 foundations, which range from the search for life’s value and meaning (moral philosophy, epic poetry, religion and political thought) through understanding human interaction in modern institutions (anthropology, sociology, political science, economics) and gaining facility in mathematical reasoning to the scientific understanding of the natural world (natural sciences) and making connections between the classroom and the world beyond the university (internships, community engagement, study abroad).

ALL-ROUNDED

At the end of the day, a student graduating with a BSc in neuroscience would have also taken courses in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. A BA graduate majoring in international studies would similarly have also taken courses in the arts, humanities, and natural sciences. Such graduates are so well-rounded and versatile that they easily find their niches in the post-graduation dispensation.

This is the kind of education we need in our universities. The kind that opens up and expands our students’ minds with critical thinking skills and multiple interdisciplinary perspectives, thereby equipping them with the capacity to change their society and their world.

Otherwise to demand that universities embark on narrowly training for the labour market is to negate the very essence of the university. With such utterances one wonders whether our leaders have expert advisers on various policy issues who help craft their speeches.

In the final analysis, I am disposed to agree with Wandia Njoya (Daily Nation, September 26, 2010) who, in response to Ruto’s earlier dismissal of the humanities, noted that “Ruto’s lack of imagination in thinking through such an important and complex problem shows that he needed to have taken courses in history and in literature for at least a semester.”

In his current utterance, Ruto claims to have been “a good student of history.” Yet if all he remembers from history is Vasco Da Gama going somewhere, discovering something, and dying, then really, he drank very shallowly at the fountain of historical knowledge.

History is perhaps the most important of all subjects. It inhibits and defines us and, quite often, it haunts us. We have to constantly go back to history to analyse it in order to understand who we are and how we came to be what we are.

It is only in this way that we can grasp the present and, ipso facto, creatively engage in efforts of constructing a future of our liking.

A society that forgets its history or that doesn’t correctly interpret its history, is a doomed society because it is bound to repeat its past mistakes over and over again with devastating consequences.

Wanjala S. Nasong’o is a Professor of International Studies at Rhodes College, Memphis, Tennessee, in USA. E-mail: [email protected].