If Waigwa Wachira lived for hundred years there surely would be no tears

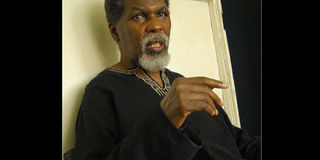

The late Prof Waigwa Wachira, Director University Of Nairobi, Free Travelling Theatre. Literary scholar Henry Indangasi pays tribute to a colleague who left a mark in the world of music, film and drama. PHOTO| ANTHONY NJOROGE

What you need to know:

- Although his height, good looks, acting prowess and rich melodious voice gave him a larger-than-life public persona, Waigwa Wachira was actually an introvert.

- I called the Director of the programme, Professor Elijah Lovejoy, who was based at the University of Nairobi and asked him if he could do something for Waigwa Wachira.

- I have lost a sincere and honest friend. The department has lost a great and irreplaceable drama teacher. And the nation has lost a literary icon.

Yes, he was an accomplished actor, with a national and inter-national reputation; but in his personal relation-ships, Waigwa Wachira did not act. There was nothing fake or phoney about him. If he liked you, he liked you. If he didn’t, he didn’t.

Although his height, good looks, acting prowess and rich melodious voice gave him a larger-than-life public persona, Waigwa Wachira was actually an introvert. And you know what they say about introverts; that they are the deep thinkers, creators of artisitc works, inventors, the ones who push back the boundaries of human knowledge. Like other introverts, Wachira had very few friends; and I would like to believe I was one of them.

In all those years we worked together in the Department of Literature, and in all the 15 years I was his Head of Department, and in spite of the fact that he was very loyal to me and the department, Waigwa Wachira never referred to me by my title: Chair or Professor. He never even called me by my real name. To him I was Conrad, even in the presence of people who had never heard of Joseph Conrad. For those who might not know, it was because I had done my doctorate on the Polish-born English writer.

Waigwa Wachira spoke idiomatic English fluently and effortlessly. In a country where bad pronunciations have proliferated, our late friend and colleague was in a class of his own. A large number of us educated Kenyans think that English has only the five vowel sounds we find in Kiswahili – a,e,i,o,u. We are tone-deaf when it comes to the other 15 vowels. We don’t know that the language has long vowel sounds and double vowel sounds, otherwise called diphthongs. We don’t know that there are rules that govern English stress and English intonation. Our departed friend had learnt to pronounce and articulate these sounds. Is there any wonder then that he successfully auditioned for roles in international movies, including the Hollywood film Gorillas in the Mist?

Waigwa Wachira had a way with words. He would come up with a particularly clever turn of phrase. One day he came to my office. He used not to knock, he would just breeze in. And that is what he did on that day.

“Conrad, lets go do tea in the cafeteria,” he said. He was a teetotaller, so he never talked of the Senior Common Room where beer would be served. And as usual, he said it with such charm, I couldn’t say no.

On our way to the cafeteria, near Taifa Hall, we bumped into Waeni Ngoloma. She teaches French in our Institute of Diplomacy and International Relations. Waigwa Wachira held her hand; he had these handshakes that lasted for ever.

“People say you are very beautiful,” he told her and paused for effect. “But that is a gross understatement.” Waeni Ngoloma couldn’t help laughing.

In the world of drama, Waigwa Wachira was a perfectionist. He had no patience with mediocrity. Those of us who were around in the late 1970s remember the day that, as an adjudicator for the National Schools Drama Festival, he stopped a performance and ordered the actors to leave the stage. According to him, the performance was stupid and boring.

Of course he paid for it. The National Drama Committee banned him from any future adjudication. He took them to court for defamation. The magistrate ruled in his favour; but the committee never invited him again. And Waigwa Wachira never stopped believing that if you set out to educate and entertain, then you should do just that. You have no business putting uninspired nonsense on stage.

Let me say something about the artistic side of Waigwa Wachira. He was immensely gifted. His play A Gift From a Stranger, published by the Kenya Literature Bureau, was nominated for the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature.

He was given an award by the University of Nairobi for the brilliant performance. But let me also tell you, KLB had to coax and cajole and entice him to allow them to publish it. And the KLB Chief Editor, Patrick Kyunguti, told me Waigwa Wachira couldn’t stomach any frivolous editorial interventions.

The reason he was reluctant to give his manuscripts to publishers was simple; he didn’t trust them. To him, the idea that a publisher would give you 10 per cent in royalties and pocket 90 per cent was downright obscene. So, our late colleague had a bunch of manuscripts he was never going to give to a publisher. The most notable was Paper in a Hurricane, which was performed several times by his Theatre Arts students.

His distrust of book publishers extended to music producers. Waigwa Wachira took a loan and paid for the production of his own music.

That song, Marry Me, that made school girls such as the young Miriam Musonye go wild, was a product of this effort. But with respect to music, luck was not on his side. One day, his car, which was packed at the University of Nairobi, was broken into and the carton containing his records stolen. Waigwa Wachira was devastated. He had hoped to make money by selling the records to people at the university. The idea was to market his own products.

Let me now tell you the back story to Waigwa Wachira’s doctoral studies at the University of California Santa Barbara, which is not in the public domain. We had an exchange programme called the University of California Education Abroad Programme. Waigwa Wachira had been talking about going abroad for his PhD. So, having been a beneficiary of this programme, I advised him to apply. This was in the late 1980s.

He sat the so-called Graduate Record Examination but flunked.

“They brought questions in trigonometry. This is stuff I did ages ago. How could I have remembered?” he told me.

“In your shoes, I would also have flunked the exam,” I said, wondering how else to empathise with him.

I called the Director of the programme, Professor Elijah Lovejoy, who was based at the University of Nairobi and asked him if he could do something for Waigwa Wachira.

“There is nothing I can do. If you fail the GRE, you fail.” And he made it sound like the GRE was some sacred vetting system that took you to heaven or to hell.

I then wrote a long, impassioned letter to the admissions authorities at UC Santa Barbara. Using all manner of superlatives and hyperbole, I told them that in drama Waigwa Wachira was a national icon, and if they trained him for us they would have helped not just the University of Nairobi but Kenya as a whole. I urged them to ignore the GRE results. Then I ended by telling them I was myself a product of the University of California system and that they should trust my judgment. Fortunately, they took my word for it, and Waigwa went to UC Santa Barbara for his PhD.

One or two semesters after, Professor Lovejoy rang me.

“Waigwa Wachira’s professors at UC Santa Barbara are excited about him. It’s like he is their dream student,” he said.

And I was saying to myself; ‘this is the same guy who thought the GRE was the gateway to heaven!’

Noam Chomsky, the famous American linguist, once described modern intellectuals as “a herd of independent thinkers.” Waigwa Wachira did not belong to any “herd.” He was genuinely independent-minded.

When he returned to Kenya, he came across to me as being more solid and more academically grounded. I never heard him spouting those pedantic platitudes about Post-modernism and Post-colonialism that characterise other scholars who come from abroad.

Let me end this eulogy by talking about an aspect of our colleague that the literary community will sorely miss. In his acting, Waigwa Wachira had a formidable stage presence, a distinctive theatrical persona. Those of us who watched him acting as Sizwe Bansi in Athol Fugard’s play could testify to his complete transformation. He wasn’t just reciting lines he had memorised. There was nothing robotic about him.

Yes, he was an accomplished actor, with a national and international reputation; but in his personal relationships, Waigwa Wachira did not act. There was nothing fake or phoney about him. If he liked you, he liked you. If he didn’t, he didn’t; and he showed it.

I have lost a sincere and honest friend. The department has lost a great and irreplaceable drama teacher. And the nation has lost a literary icon.

May his soul rest in eternal peace.

Henry Indangasi is a professor of literature at the University of Nairobi. Email: [email protected]

Waigwa’s hit song: 'Will you marry me?'

If I live a hundred years, there will be no tears

Coz I will fill your waking hours with a bunch of flowers

A bunch of flowers

In your waking hours

I will be there to keep you away from pain in the sun and rain.

And I will close my eyes and say a prayer for you

And each day bring you ecstacy endlessly

Ecstasy... endlessly...

And each day bring you ecstacy endlessly

So darling won’t you marry me and carry me

Across the sea to the starry skies and to paradise

Won’t you marry me?

And carry me

Across the sea to the starry skies unto paradise

Do you take him

To be your lawful wedded husband

To love, to cherish and to hold?

I do.

And do you take her to be your lawful wedded wife

To love, to cherish and to hold?

I do.

So let us close our eyes and say Amen...

We thank you Lord in every way Amen...

Everybody say Amen

Amen...x3

Thank you Lord in every way... Amen x3

Thank you Lord in every way...

Amen.

Thank you Lord in every way...

Amen...