The architectural masterpiece that combines heritage and art

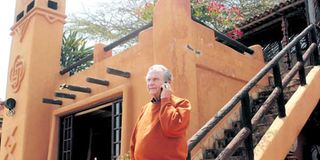

Mr Alan Donovan, founder of African Heritage House next to the iconic building. It has been gazetted as a heritage site and is maintained by the National Museums of Kenya. PHOTO | JAMES EKWAM | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Every so often, a loud cargo train chugs its way past the AHH, as the Heritage house is popularly known, lending a charming, rustic feel to the otherwise raw wilderness.

- Its style and architecture, modelled after Mali’s Great Mosque of Djenné, earned it a spot in the world’s foremost architectural magazine in the world, Architectural Digest.

- The house is located at the end of a narrow driveway marked “Alan Donovan”, which lies right next to the church.

African Heritage House (AHH), the iconic building that sits elevated at the Athi River edge of Nairobi National Park, offers its visitors some of the best views of the park.

If you stand at the second floor balcony of this house, you are treated to undulating views of the rolling vistas of shrub and grassland that make up the park, dotted by grazing herds of zebra and antelope.

Just 100 metres away, the Nairobi-Kisumu railway snakes through the land, forming the boundary between the park and the property on which the house stands.

Every so often, a loud cargo train chugs its way past AHH, lending a charming, rustic feel to the otherwise raw wilderness.

It is breathtaking, despite the towering pylons that dot the landscape as far as the eye can see, often getting in the way of a perfect unmarred shot of the sunset.

TREASURE TROVE

Picturesque views aside, AHH is an art lover’s dream, its very style and architecture, modelled after Mali’s Great Mosque of Djenné, earning it a spot in the world’s foremost architectural magazine in the world, Architectural Digest.

It was the first house in sub-Saharan Africa to be featured in the publication.

And inside this house is a treasure trove of African art, collected through the decades from some 18 African countries, curated and preserved not in the forbidding, prohibitive style of museums but in the warm inviting way of an African home.

It is the home to priceless African art, artefacts, musical instruments, jewellery, furniture, textiles and books from around the continent.

You access AHH by driving up to Mlolongo, then looking for a large signboard for Kasina AIC Church, located on the service lane towards Nairobi.

The house is located at the end of a narrow driveway marked “Alan Donovan”, by which lies right next to the church.

LIVEABLE MUSEUM

The house and its contents are synonymous with Alan Donovan, an American artist who made it his mission to collect African art and to give it a home in Kenya.

Donovan succeeded beyond his wildest dreams, turning his private home into the liveable museum and gallery that is the African Heritage House.

So popular has the house and its contents become that it has attracted visitors from far and wide, making it Africa’s most photographed house.

The house’s colourful story would have ended on this high note were it not for the fact that it lies smack in the middle of the proposed site of the new Standard Gauge Railway.

From that sad day in January last year when Donovan found out that AHH was on the chopping block to make way for Kenya’s modern railway, he has been in a fight to save the house and its art.

“On the day, they told me that my house will have to be demolished to make way for the railway, I developed clots in my leg due to stress and I had to be hospitalised. I am better now but my leg still acts up once in a while,” he says.

His story is eerily familiar to that of Joseph Murumbi, Kenya’s second Vice President and one of Africa’s biggest art collectors, who died of stroke after discovering the ruins the government had made of his prized house in Muthaiga.

SPIRITED EFFORTS

Murumbi had bequeathed the house and all its treasures to the government under the agreement that they would preserve it as an art institute.

But the government reneged on that promise and let the house fall into ruins, damaging some of the art in it.

Most of that art, and whatever else Murumbi and his wife Sheila collected, now lies at the National Archives and the Nairobi Gallery, thanks to Donovan’s spirited efforts to ensure that the Murumbi collection does not go to waste.

The fates of Murumbi and that of Donovan have been intertwined ever since the 1970s when the two teamed up to collect African art, and to exhibit it under the African Heritage galleries, which they set up in Nairobi.

Donovan’s share of the art is what now lies at the African Heritage House.

A year after the house’s imminent destruction was announced, the tide turned in Donovan’s favour when the house became gazetted in March this year as a national monument.

The gazette notice by Cabinet Secretary for Arts and Culture Hassan Wario means that the house, as well as 20 other sites, are now under State protection as an integral part of the country’s culture.

Although Donovan retains ownership of the house, the Kenya National Museum will now step in in an oversight role to ensure that the building, its compound and the art in it are preserved as per the requirements of the law.

STALEMATE OVER

But was it too soon to celebrate?

In June, wildlife conservationist Paula Kahumbu started an online campaign challenging AHH’s legitimacy as a protected site, suggesting that the house be dismantled after all to make way for the railway.

Kahumbu’s argument was that saving AHH must not be at the expense of losing valuable park land.

The stalemate seems to have been resolved last week with an announcement by new Kenya Wildlife Service Richard Leakey that the railway will be allowed to run on Nairobi National Park’s land, on condition that bridges will be built on affected areas to avoid disturbing the animals.

This agreement was reached after consultative meetings with Kenya Railways and the National Land Commission.

PASSENGER TRAIN

KWS also demanded monetary compensation for disturbances caused during the building and the running of the railway, saying that the money will be used for conserving wildlife.

“I am very happy with the decision by KWS to demand that any sections of the railway that pass through the park be elevated on bridges so as not to hinder animal movement. I also note that General Electric is providing 20 passenger train coaches to Kenya Railways. I hope these will be used for a new “luxury” train to pass through the parks. A new daytime passenger train could be a wonderful attraction for tourists to Kenya as well as local people,” he said.

So things look good for the cultural and anthropological treasure that is African Heritage House.

It seems to have escaped bulldozers.

At least for now.