Breaking News: At least 10 feared to have drowned in Makueni river

Binya was a prolific restless spirit with a funny bone, big heart

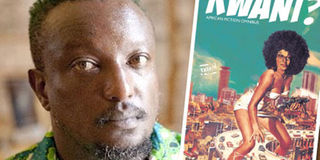

Binyavanga Wainaina. The Kwani? production process was an exceedingly brutal one. He could decide at a whim that the look of the full journal was terrible and we had to start again. PHOTO | FILE | NMG

What you need to know:

He would champion someone’s work both artistically and practically in incredible ways.

He also not only instinctively understood how narrative worked, but more importantly he had an unfailing knack for understanding the person who was writing it.

And yet for all his kindness, his aesthetic standard was so fixed that he would never compromise.

I had two first meetings with Binyavanga Wainaina.

The first at Lenana School where he was two years ahead of me. I met him again in 2005 at his home-from-home Java Mama Ngina. He was now founding editor at Kwani? and larger than life.

WITHOUT NOTICE

As a student in South Africa, I had sent him a short story titled ‘The Applications’, which he had loved.

When I returned to Nairobi, we met and he asked me what I thought about Kwani? (there were two issues out). I blurted out that it was great but it needed to capture the post-2002 moment more by publishing creative non-fiction. I did not realise that this really was an informal job interview of sorts.

The next time we met he told me about Central Bank whistle-blower David Munyakei and willed me into writing his story. He also invited me to edit the next Kwani? (no 3).

I quickly learnt that everything with Binyavanga happened at warp speed. Even after becoming perhaps the most visible new writer in Kenya after winning the Caine Prize, he spent most of his time in these years talking about the work of others.

For such a confident and brash person on the outside, he could be very reticent about his own work.

When stories that he’d written quietly emerged somewhere, it was almost without notice, even for those who spent a lot of time with him. But the glimpses of him at work taught me how unserious I was about my own writing.

He was excruciatingly exacting with himself — much more so than with many writers he published. The Kwani? production process was an exceedingly brutal one. He could decide at a whim that the look of the full journal was terrible and we had to start again.

OBSESSIVELY PUGILISTIC

He was generous to a fault with so many artists, not only writers. He would champion someone’s work both artistically and practically in incredible ways. He also not only instinctively understood how narrative worked, but more importantly he had an unfailing knack for understanding the person who was writing it.

And yet for all his kindness, his aesthetic standard was so fixed that he would never compromise. He did not mind being cruel if necessary. And so he made so many enemies, particularly with those he described as the textbook and “campo Literary Mafia and their boiled sukuma wiki way of thinking”.

Binyavanga was terribly funny when he chose but could also be a bad sport. Social media at times brought out the worst in him. It was the perfect space for fuelling a nature that could become obsessively pugilistic. When there was no one to talk and rant with in the early hours of the morning, it was a space to let it all out.

In his healthier days, no one was as hardworking — he was always quietly writing another novel script. By the time he finished One Day I Will Write About This Place, he’d destroyed several fiction manuscripts. Binyavanga’s creative impulse was his driving force and he very much made his own yardstick for cultural value.

He famously rejected recognition as a Young Global Leader of the World Economic Forum while, through his work as Kwani? editor, financing a studio for Ukoo Flani Mau Mau. He was the emotional force behind 24Nairobi, the only supporter of photographer Nick Ysenburg, who appeared from nowhere wanting to produce a collection of photography and writing featuring yet-to-be-known names such as Boniface Mwangi and James Muriuki.

AFRO FUTURISM

He was the only Kenyan writer to have appeared on Oprah. When he took up a position at Union College in Upstate New York, Kwani? had ballooned into a journal, a literary festival, book series and a monthly Open Mic. And he let it breathe by leaving me to make my own mistakes as the new editor. He was unfailingly generous with his time when I asked. He continued to open doors.

His advice was uncanny. Nobody understood African literary and cultural shifts better. He anticipated the Afro Futurism boom years before.

As How to Write About Africa continued to spark conversations, as One Day was named New York Times notable book and he became in constant demand as a speaker internationally, Binyavanga remained a restless artist and his creative spirit an ever-wandering one.

He was seriously considering becoming a curator before he fell ill in 2016. And he started writing a fantasy novel in Germany at the DAAD fellowship in 2017.

His first stroke happened weeks after he’d submitted the final manuscript of One Day and came as a complete shock to his friends.

It was as if he’d expended all his energy in the book. And in true Binyavanga fashion, he could not quite decide what the book was — it was part memoir, part travelogue and part political rant. But read again the brilliant section about Ki-may, the Babel of his childhood for all that did not speak English. And yet there was a part of himself he had not given to that book. When he published the lost chapter and came out publicly as gay, it opened up both him as a person and his writing.