Doctors assess sector's growth in new book

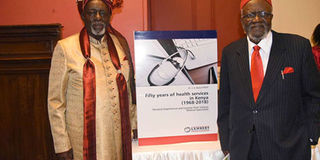

Chest specialist Joseph Aluoch (left) and former Health Minister Isaac Omolo Okero launch the book Fifty Years of Health Services in Kenya, at Nairobi Club on February 20, 2019. PHOTO | EVANS HABIL | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Dr Aluoch recalls that a number of the medicines used at the time used to emit strong smells, which combined to make a cacophony of unpleasant odours.

- A chapter by Dr Odhiambo on the history of radiology in Kenya reveals that Kenya’s first x-ray machine was installed in Kisumu in 1951.

When you bring together more than 30 Kenyan medics and ask them to recount the profession’s progress since 1968, you are bound to get interesting stories.

Fifty years ago, they will tell you, a reputable doctor’s starting salary was Sh960 a month.

You might hear stories of rudimentary machines and first encounters with HIV, a dreaded virus when it first hit.

These experiences, and many more, have now been made into a book: Fifty Years of Health Services in Kenya (1968-2018), launched in Nairobi on Wednesday.

Dr Joseph Amolo Aluoch, a 76-year-old chest specialist, edited the 372-page book written by 37 different people.

He writes in the introductory sections of the book that he used to earn a monthly salary of Sh960 after being employed on April 1, 1968.

“I was among the highest paid at that time. There were very few people in the so-called ‘four-figure bracket,’” he notes.

“Within one year I was able to buy myself a Volkswagen valued at Sh12,000 with a loan from the National Bank of Kenya.”

The Sunday Nation brings you some of the interesting highlights.

1. Hospitals used to be very smelly

Dr Aluoch recalls the state of tuberculosis (TB) patient facilities.

“The TB wards were chock-full of cases of emphysema (lung disease) whose smell from the gate of the hospital was unmistakable,” he writes.

Because the procedures of treating wounds were also rather basic, he says, “you could smell festering wounds from the wards at the gate of the hospital”.

He also notes that a number of the medicines used at the time used to emit strong smells, which combined to make a cacophony of unpleasant odours.

2. When men in a research project demanded their foreskins back

One of the chapters is written by lawyer Ambrose Dixon Otieno-Rachier, where he weighs in on the legal issues that have overlapped with the practice of medicine over the years.

He recalls an incident involving a University of Nairobi professor, who is his friend. The professor had found 40 men who were willing to take part in a study on male circumcision.

Having secured their consent, the professor thought all was well. Things changed when they learnt that he had shipped the foreskins overseas.

“To the horror of the professor, the participants came to demand back their foreskins, which they did by coming to protest at the good professor’s office,” he writes.

3. Why did the first crop of doctors die young?

Renowned psychiatrist, Dr Frank Njenga, has also authored a chapter in the book. One of the issues he tackles is the death of doctors.

“At a recent conference organised by the Kenya Psychiatric Association, Dr Joseph Aluoch and Dr Dan Gikonyo were able to illustrate the fact that morbidity and mortality among doctors is surprisingly high. The class of 1970 at the University of Nairobi illustrates this point well,” Dr Njenga writes.

“The causes of death in that class range from infectious disease and non-communicable diseases including cancers as well as possible psychiatric disorders,” he adds.

Dr Njenga observes that a good number of doctors who graduated before 1963 died due to mental disorders.

“It is reported that a number drank too much and died of the consequences of alcoholism. Speculation has it that they were stressed by the conditions of work,” he writes.

4. Kisumu was the first region in Kenya to have an x-ray machine

A chapter by Dr A. Odhiambo on the history of radiology in Kenya reveals that Kenya’s first x-ray machine was installed in Kisumu in 1951.

Kenyatta National Hospital, then known as King George IV Hospital, got its first machine in 1956.

Why did the colonial government give priority to Kisumu? Dr Adhiambo writes that it was because the town was then the headquarters of the Ministry of Health.

5. Kenya’s first kidney transplant was due to urgent necessity

The year was 1978. Doctors had a 10-year-old girl whose kidneys had been destroyed by accident.

On the other hand, there was a patient dying from brain haemorrhage and doctors decided to try a transplant.

Prof Seth McLigeyo of the University of Nairobi’s medicine department writes in this chapter that the urgency of the operation created the need to conduct it in Kenya.

“(Otherwise) between 1978 and 1984 most of our patients were transplanted in Britain or the United States of America after varying periods of dialysis,” Prof McLigeyo writes.

6. The scary entry of HIV into Kenya

Erastus Amayo’s chapter on neurology, a branch of medicine that deals with the nervous system, looks back at the panic caused by the entry of HIV in Kenya — which was first reported in 1984.

“We could admit 50 or more patients at the beginning of the week and, by the end of the week, the ward would be empty again and waiting to devour more people. The initial period brought home the apparent hopelessness of medicine,” he recalls.

Mr Amayo recalls that there was no drug that appeared to soothe the symptoms of Aids in any way.

7. VIPs tried blood transfusion but it was no match for HIV

Dr Aluoch, the editor of the book, also gives his perspective on the vagaries of the HIV and Aids pandemic in its early days.

“In the 80s, there was virtually no treatment for HIV in Kenya or, for that matter, anywhere in the rest of the world.

"Most patients were literally nursed in the wards as terminal cases. Indeed, HIV diagnosis was a death sentence. Many wards in the country were filled with wasted, miserable-looking patients literally staring death in the eyes,” he recalls.

“The few rich and powerful Kenyans who contracted HIV/Aids took a trip overseas to try the then fashionable treatment of exchange blood transfusion. Regrettably, they too came back and went straight to their graves sooner or later,” the chest specialist.

8. Most epilepsy patients in hospital have tried traditional interventions

One interesting observation Prof Paul Kioy has made while handling epilepsy patients is that they go to hospital after trying their luck with witchdoctors, because many Kenyans believe the disorder is caused by evil spirits.

“The proportion of people with epilepsy that are not receiving adequate medical treatment in the country is estimated to be between 60 percent and 80 percent,” he writes.

9. Some medicinal herbs are a gem, but they are hardly cultivated

Dr Jennifer Orwa, the chief research officer at the Kenya Medical Research Institute, has a chapter on traditional African medicine.

She notes that it is an area that conflates with witchcraft because it is still being regulated by the Witchcraft Act that came into effect in 1925.

One concern she raises is that the herbs that are known to be medicinal are hardly nurtured.

“Plant material that supplies the Kenyan market is almost exclusively collected from the wild, making the traditional medicine industry unsustainable,” she writes.

10. The first doctors’ strike and its lasting effect on the profession

The editor provides insight into the first doctors’ strike of 1971, of which he was part.

“That strike marked a major turn in the attitude of healthcare workers in Kenya, especially doctors towards public service.

"Things have never been the same. Commitment was thrown out of the window, and conflict of interest came in through opened doors,” the veteran medic notes.

He concludes by stating that doctors should not use innocent patients as pawns: “Our first duty is to care for the patient. We must insist on the doctors holding aloft this defining ideal.”