Hits and misses in new book on Mohamed Amin’s work

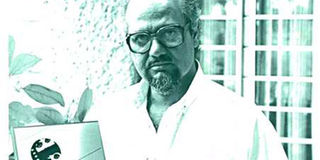

Mohamed Amin displays an award he won in 1987 for his short film Give Me Shelter. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- But by selling it at more than $200 dollars (Sh20,200), it appears that Salim Amin has cut out big fans of Mo from accessing this book.

- Had a political scientist or historian gone through this work, it would have added much more value to it and identified the many errors.

Of all Kenyan photojournalists, Mohamed Amin is still the best known. His death aboard the hijacked Ethiopian airliner, flight 961, some 22 years ago, shocked the world and for a simple reason.

His epic images about the famine in Ethiopia allowed the world to see, for the first time, the gravity of the crisis.

In an exclusive story, first published by the Nation, Amin warned that “between five and seven million people could die in the next two months if the world does not act”.

This story and accompanying images of death and despair were picked by all media houses.

It forced the world to act and also saw top musicians compose the song “We are the World” to rally everyone to help Ethiopia out of famine.

It also saw Bob Geldof and Midge Ure organise the Live Aid Concert in July 1985 at Wembley Stadium, which raised $127 million.

RISK TAKER

Amin had also lost his arm in Ethiopia in 1991 as he covered an ammunition dump and he had to use a prosthetic arm, which allowed him to operate his lens.

It was in Ethiopia that Mo, as he was better known, earned more accolades and calamities.

“My father was best known as a great frontline photojournalist but he spent more time documenting his country’s beauty, culture, people and leaders than anything else,” Salim Amin writes in a new coffee table book: Kenya Through my Father’s Eyes.

The foreword is written by Chip Duncan, a filmmaker and author, who describes photojournalists -- such as Mo -- as “risk takers … who put the power of story above their own comfort and safety”. And that is how Mo lived.

On November 23, 1996, Mo was on board Ethiopian Airlines flight 961 when it crashed off Comoros during a botched hijacking together with his Camerapix colleague Brian Tetley. It was a tragic story.

HIJACKERS

The plane under Captain Leul Abate was on the regular Addis Ababa-Nairobi-Brazzaville-Lagos-Abidjan route when it was taken over by some Ethiopian hijackers who demanded to be flown to Australia to seek political asylum.

They claimed they had a bomb. The only problem was that the plane did not have fuel to reach Australia and Captain Abate told the hijackers as much as he flew south.

It was his third dalliance with hijackers. “Keep flying,” one of the hijackers ordered Capt Abate, who was trying to convince them to let him land and fuel the plane.

After four hours of flying — having overflown Nairobi — he told them: “There is an island here, which is way out of Africa so this is your last chance to refuel. They said no, we don’t need any refuelling. We go as far as the aircraft flies then we crash …” and I said, “If you don’t want to reach your aim, and you want to die in the air why do you have to kill all those innocent people,” and they said “never mind, we are making history”.

Capt Yonus Mekuria was the co-pilot. “I never for a moment thought that anybody, in his right mind sitting there watching the fuel gauge going down and letting it go to empty,” Capt Mekuria would later tell a TV station.

CRASH-LAND

The island below was Comoros and was the only place they could either land to refuel or ditch.

“I told the lead hijacker, guy we have 30 minutes to leave. Unless you allow me to land and refuel.”

At 21,000 feet, both engines stopped and the captain started preparing to crash land the 150-tonne Boeing 767, which was falling out of the sky at 2,000 feet per minute but still moving at 320km per hour.

The captain knew he could only glide using the flaps for less than 65 kilometres before crashing.

He then decided to ditch the plane 500 metres off Le Galawa Beach Hotel near Mitsamiouli at the northern end of Grande Comore island — where they could easily be rescued.

But at a speed of more than 300kph, the plane cartwheeled and broke apart killing, among many others, Amin and his co-writer Tetley.

The three hijackers were among the dead. It is now known that the plane hit a coral reef below the water — which did most of the damage as many were trapped inside the fuselage.

Before it crashed, Mo is said to have attempted to rally the passengers against the hijackers. Others claim he was trying to negotiate.

NYAYO ERA

The new book by his son, the one who keeps his company Camerapix running, is the photographic story of Kenya giving a keen reader a chance to see some images never seen before.

While the book is powerful on images, the same cannot be said of the text and general editing.

Some pictures have no captions, and some of the figures are not identified.

More so, the book would have been powerful had the writer took time to research on the political moments some of the images were taken — and refreshed the reader with the dramatic moments.

For instance, there was never an official constitutional drafting group, which wanted to limit Moi’s ascendancy to presidency.

What we had was a group campaigning to have parliament change the constitution to thwart Moi from acting for 90 days pending elections and this was outfoxed by Charles Njonjo.

And we don’t seem to do justice to Moi by summarising his political life in less than 200 words and pictures on Nyayo era have no captions.

TOM MBOYA

Again, I am not sure why Tom Mboya is only remembered for organising the airlift when it is well-known that he was the architect of labour movement in Kenya, and was actually one of the negotiators for Kenya’s freedom at Lancaster.

Actually, the British and Americans thought he would be a better Kenyan leader than Jomo.

Later on, he would be one of the brains behind the Sessional Paper No. 10, which defined Kenya’s economic policies after independence plus many other accolades.

On the airlift, it did not start in 1953 (which was the start of Mau Mau war and emergency period), but in 1959 when 89 students left.

Similarly, why Mwai Kibaki’s story does not include his years as Moi’s vice-president is a minus to details and with the two images on him, any person with no prior knowledge of Mr Kibaki would hardly know anything about him — or his presidency.

CONSERVATION

The book allows us, however, to see the role played by Mo in bringing out conservation stories.

It was his images on Ahmed, the Marsabit elephant, which earned presidential protection, thanks to its long tusks each weighing about 70kg.

There is also the story of George and Joy Adamson — who devoted their lives preserving both Meru National Parks and Kora National Reserve.

Joy would later write a book, Born Free, which captured the story of Elsa, the lioness cub that she had domesticated.

Their tragic deaths captured the nation’s attention and I am not sure whether Mo went back to their resting places.

There is much more on conservation in this book — but I doubt whether the decimation of elephants in the 70s and 80s could be blamed on poachers with guns and bows and arrows rather than a cartel that included government officials.

DISORGANISED

I think the same network that existed in 1970s still exists with the same markets.

While the actual hunting by big-game hunters had stopped, the wanton destruction was left to ordinary poachers who fed to the networks.

There are other iconic images on Safari Rally, athletes including the legendary Kipchoge Keino, and horse racing.

The problem is that the book is not organised in any chronological order of events or themes.

For instance, the pictorial part on Baba ya Simba (George Adamson) on page 47 could have been merged with “She was Born Free” on page 133.

Overall, the most interesting pictures are on the 1970s fashion.

But what we lack is the context on which Amin took all those images that have been included in the book — and one is left with the feeling that it was done in a rush by the editorial team.

PRICE

As a plus, the book comes out with augmented reality content — which is a first in the country and where you can download a video by scanning an image in the book.

But by selling it at more than $200 dollars (Sh20,200), it appears that Salim Amin has cut out big fans of Mo from accessing this book.

Had a political scientist or historian gone through this work, it would have added much more value to it and identified the many errors.

For instance, Mboya was not born in 1969 (page 25) — that is when he died. Moi’s other name was Toroitich not “Toroitch”.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga was not vice-president in 1978 (page 19) and Nairobi did not achieve city status in 1919 (page 141) but in 1950, when it was elevated from municipal status.

Before 1919, Nairobi was governed by a municipal committee which was replaced with a structured municipality until 1950.

Kenya Through My Father’s Eyes, however, allows us to see the country that Mo walked through.

The events that he covered and his sense of imagination while taking images.

[email protected] @johnkamau1