The ruthless governors who ruled over Kenya had military backgrounds

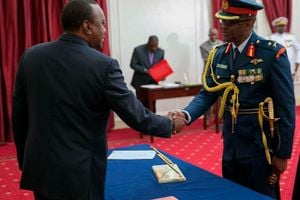

The country’s last colonial governor Sir Malcolm MacDonald, right, during a meeting. FILE PHOTO |

What you need to know:

- Many of Kenya’s colonial governors were celebrated members of the British officer class.

- They were also more than prepared to stamp their authority on the Kenyan colony.

While the Constitution provides for today’s governors to be chosen through elections, before Kenya’s independence it was the UK royal office that appointed them.

For the colonialists a military background and ruthless character were some of the attributes suitable for one to be appointed governor. For decades the political rulers of the country were an eclectic mix of bureaucrats who represented the British government.

They had an often similar pedigree and were more often than not members of the British aristocracy. In addition, they were usually well-decorated military personalities to boot, and therefore easily fitted into the role of being the colony’s no-nonsense commanders-in-chief.

Among the best known Kenyan governors was Malcolm MacDonald, who from January 4, 1963 to December 12 of the same year occupied what was then the governor’s mansion which later became State House.

Unlike his predecessors, Sir Malcolm was referred to as the Governor-General of the then Kenya colony, and his task during the one year he occupied the position was to oversee the country’s transition to independence.

An affable, liberal man, he was much unlike his predecessor, Sir Patrick Muir Renison, who was governor from October 1959 to 1963.

Holding the position during the politically tricky years that were the build-up towards independence, Sir Patrick had little quarter with the African politicians that he only reluctantly accepted were to take over the reins of power.

Sir Patrick was particularly loath to accept that future Kenyan prime minister and founding President Jomo Kenyatta would eventually occupy the mansion on the hill.

DEROGATORY REFERENCE

His derogatory reference to Kenyatta as “a leader unto darkness and death” has to this day remained prominent among the most memorable quotes from the colonial administrators.

Renison’s predecessor was Sir Evelyn Baring, who occupied the position between September 30, 1952 and 1959, and who gave his name to the famous Baring biscuits that were for years synonymous with the pastry fare in the East African region.

Apart from that achievement, Baring had the tough job of dealing with the nascent Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya, and was in fact responsible for declaring a state of emergency in October 1952, and overseeing the police and military operations that were associated with that period.

The man he replaced at the governor’s mansion was Sir Philip Euen Mitchell. He served as the governor from December 11, 1944 until the post was taken over by Baring in 1952.

Oxford-educated, Mitchell was an avid fisherman who also served as the governor of the then Uganda colony between 1935 and 1940, and then as the governor of Fiji from 1942 to 1944, when he moved to Kenya.

Mitchell had joined the Colonial Administrative Service in 1913 and worked in the then Nyasaland, and served in the King’s African Rifles during World War I, when he reportedly became fluent in Kiswahili. In 1922 he was promoted to District Commissioner in Tanga in the then Tanganyika colony.

In mid-1940 Sir Philip was transferred to Nairobi to co-ordinate the East African war effort. He was given the delicate job of administering the Italian African colonies that had fallen to the British. In January, Mitchell signed a treaty with Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia.

The highlight of Mitchell’s administrative career came when, in February 1952, he received Princess Elizabeth on a visit just before her father died and she ascended the throne as Queen Elizabeth II.

That aside, after so many eventful years in the continent, Mitchell was apparently so taken by his African adventures that on eventual retirement from the colonial service, he bought a farm in Subukia, where he planned to settle.

However, Mitchell had a paternalistic attitude towards Africans, considering that they needed help from white settlers to become civilised.

Believed by many to have been among the more progressive British administrators, by 1947 Mitchell had become highly conservative and his views regarding Africans were barely veiled racism.

He was hence able to state in his book, The Agrarian Problem in Kenya, that Africans were, in his view, “a people who, however much natural ability and however admirable attributes they may possess, are without a history, culture or religion of their own and in that they are, as far as I know, unique in the modern world”.

As if to make his racist opinions crystal clear, he was also in May 1957 to bluntly advise Arthur Creech Jones, the then Secretary of State for the Colonies, that it was Britain’s task to civilise Africans, who to Mitchell were “a great mass of human beings who are at present in a very primitive moral, cultural and social state”.

Baring, Mitchell’s successor as Kenya’s governor, was to prove that the two were birds of a feather. Faced with the Mau Mau rebellion that lasted for most of his stay at Government House, Baring resorted to the most brutal tactics in a bid to quash the mounting opposition to British colonial rule.

In fact, he directly or indirectly presided over some of the worst atrocities of the period, including the infamous Hola massacre.

He had been the Governor of Southern Rhodesia from 1942 to 1944, and many were not surprised when it was later alleged in the British media that he had asserted in a letter to British officialdom that inflicting “violent shock” was the only way of dealing with Mau Mau insurgents.

Just like Mitchell and Baring, many of colonial Kenya’s governors had already served or were to serve in other British Raj territories such as the then Southern Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Sierra Leone, The Seychelles, Ceylon, Uganda and the then Tanganyika. Moreover, it was not unusual for one to serve successively in several colonies as the governor.

As veteran military operatives, many of Kenya’s colonial governors were celebrated members of the British officer class. Not surprisingly, some took part in the two world wars, and also fought in major wars in Africa and elsewhere.

SETTLER CLASS

They were also more than prepared to stamp their authority on the Kenyan colony, which was no easy task. Among the challenges they had to deal with was an arrogant and obstinate settler class, the so-called Indian Question and the incessant demands of African nationalists clamouring for independence.

Among the most successful military men to serve in Kenya was Air Chief Marshal Sir Henry Robert Moore Brooke-Popham, a much decorated individual who served as the country’s governor from 1937.

He was taking over the position from Brigadier-General Sir Joseph Aloysius Byrne, yet another man with a sterling military background.