Loans and frustrations that led to Murumbi’s loss of farmland

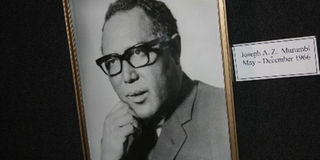

The late Joseph Murumbi. Murumbi was the man who resigned his seat as vice-president in 1966 after a few months allowing Kenyatta to appoint Daniel arap Moi. PHOTO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

Even as he dreamt of one day turning the Maasai plains into organised ranches to position Maasai herdsmen as the key producers of beef for the Kenyan market, he also aspired to help his community divest into growing cash crops such as tea, coffee, maize, barley and oats, among others.

However, unlike his art collection enterprise that won global acclaim, his farming pursuits didn’t fare that well, and he was frustrated at times over failure to get adequate funding to kick-start the project.

After selling to the government his posh Muthaiga house, where he had assembled an enviable collection of African art in 1977, Kenya’s second vice-president Joseph Murumbi and his wife Sheila moved to re-establish themselves in the Narok countryside among his clansmen.

With the help of leaders of his mother’s Uasin Gishu clan (which was relocated to Trans Mara by colonialists in the 1930s from present-day Uasin Gishu County), he was allocated a scenic 2,065-acre tract located between Lolgorian and Kilgoris in Narok, where he hoped to do farming and establish a Maasai research centre.

QUALITY BREEDS

In his 2015 biography A Path Not Taken, which was put together using mainly his private papers, he said he was helped to acquire the property by his cousin John Konchella, who was the Narok West MP and served as an assistant minister in the Health and Education dockets.

Initially, the land had been allocated to the Narok County Council by the minister for Lands Joshua Angaine, who later allocated it to Murumbi following a no-objection from the county council.

The land was called Intona, meaning “roots” in Maasai. “I have gone back to settle among my mother’s people,” he is quoted in an interview published in the book.

He dreamt of turning Intona into a model farm through which he hoped to improve the lot of his community by introducing them to modern farming practices such as keeping better quality breeds of beef cattle from abroad and even large-scale farming.

FUNDING

Even as he dreamt of one day turning the Maasai plains into organised ranches to position Maasai herdsmen as the key producers of beef for the Kenyan market, he also aspired to help his community divest into growing cash crops such as tea, coffee, maize, barley and oats, among others.

However, unlike his art collection enterprise that won global acclaim, his farming pursuits didn’t fare that well, and he was frustrated at times over failure to get adequate funding to kick-start the project.

First, he contracted an American company called Tiffany Enterprises to carry out a feasibility study for the whole of Narok district at a fee of $120,000 (equivalent to about Sh12 million at today’s exchange rate). He then approached the American ambassador in Kenya at the time Tony Marshall to help him get US aid to carry out the feasibility study but was turned down.

FRUSTRATED

But the diplomat arranged for him to get a commercial loan from an unnamed US bank that was based in Nairobi at the time, but this was also frustrated by officials of Narok County Council.

At the same time, with his mind in large-scale crop farming, he said he was negotiating with Blackwood Hodge — an English company on whose board of directors he sat — to set up a workshop in Narok town for their Case tractors, several of which he intended to purchase. But his efforts frustratingly came a cropper again.

This did not kill his spirt, though. He hoped that government officials, especially his friend, the VP and minister for Finance at the time, Mwai Kibaki, would visit his farm and see its potential.

In an interview reproduced in the book, he said he had borrowed a loan from the Agricultural Finance Corporation, although he lamented that it was a “very cumbersome procedure”. It is this loan and a subsequent one that would lead to his eventually losing the farm, now being contested by members of his family and private purchasers.