Recruitment farce seals President Kenyatta’s grip on police

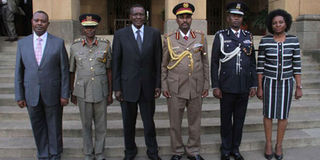

New police bosses with the Chief Justice, Inspector-General of Police and the Court’s Registrar after being sworn in. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- The interviews for the two positions of Deputy Inspector-General of Police and head of the Directorate of DCI appear to have cleared any pretence that President Uhuru Kenyatta was calling the shots.

- Curiously, NPSC had shortlisted just one candidate each for the DCI boss, Mr George Kinoti, and the Deputy IG in charge of the police service, Mr Edward Njoroge Mbugua.

- But NPSC chairman Johnstone Kavuludi saw no problem with just a single candidate being shortlisted.

- President Kenyatta had named Mr Maingi the acting DCI director taking over from the long-serving director Ndegwa Muhoro.

At the heart of the 2010 Constitution was the deliberate move to limit the Executive’s control over the security sector, especially the Police Service, that had for years been a misused political tool.

But less than eight years after the new Constitution took effect, the Police Service has steadily lost the independence the framers of the Constitution envisaged with the recent farcical hiring process of top officers signalling the latest example.

The Thursday interviews for the two positions of Deputy Inspector-General of Police (Kenya Police and Administration Police) and head of the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) appear to have cleared any pretence that President Uhuru Kenyatta was calling the shots.

When the National Police Service Commission (NPSC), an institution initially meant to be independent, published the shortlist for the openings in the national police service hierarchy on Wednesday, the public quickly noticed something unusual with the list of contenders.

The public was also asked to submit complaints against the candidates by Saturdayy — yet the senior officers were interviewed on Thursday and sworn in on Friday, raising further questions since such objections usually form part of the interview.

ONE CANDIDATE

Curiously, NPSC had shortlisted just one candidate each for the DCI boss, Mr George Kinoti, and the Deputy IG in charge of the police service, Mr Edward Njoroge Mbugua. The DIG position in charge of Administration Police had three candidates shortlisted, namely Musa Kakawa Dhadho, Noor Yaro Gabow and Vincent Kinas Makokha. Mr Kinoti, Mr Mbugua and Mr Gabow had previously been appointed by the President on January 5 to act in the positions.

And, in less than 24 hours, the candidates were also expected to get clearance from the Kenya Revenue Authority, the Higher Education Loans Board, the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission, Credit Reference Bureau and the DCI. Curiously, the media were locked out of the interviews, a departure from the transparency of previous hiring processes.

It was a shortlist that even seasoned human resource professionals are struggling to comprehend.

According to the chairman of the Institute of Human Resource Management Council Elijah Sitimah, a shortlist ought to have more than one candidate.

“One-candidate interview in an environment governed by defined policies and procedures is indeed immoral for an HR professional to attempt knowing very well that s/he will be held accountable to the written procedures,” Mr Sitimah said in response to Sunday Nation enquiries.

SINGLE CANDIDATE

But NPSC chairman Johnstone Kavuludi saw no problem with just a single candidate being shortlisted.

“Even if there is only one candidate who meets such a threshold we can only recommend that candidate to the President for appointment,” he said after the conclusion of the interviews on Thursday evening.

Mr Kavuludi declined to respond to our questions on the recruitment after promising to do so.

As well as the oddities, NPSC appeared to have been using the Thursday interviews to endorse the selections that were already made by President Kenyatta when he announced a partial list of Cabinet on January 5.

President Kenyatta had named Mr Maingi the acting DCI director taking over from the long-serving director Ndegwa Muhoro while Mr Mbugua was appointed acting DIG in charge of the Kenya Police, taking over from Mr Joel Kitili. Mr Gabow had been named the acting DIG in charge of the Administration Police in the place of Samwel Arati.

According to Mr Chris Gitari of International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), it appeared the three had substantively been appointed after the President named them given that there were even publicised handovers by previous office holders.

“It goes to show that we have lost NPSC which is now, for all intents and purposes, just a department whose role is to formalise a pre-ordained exercise,” said Mr Gitari.

But Mr Kavuludi dismissed suggestions of the President meddling in the appointment of the top police chiefs, saying the appointments were done in consultation with the commission and Inspector- General Joseph Boinnet before the President made the announcement.

RETIRE

“The law allows the President to remove, redeploy and retire a DIG from the police service before the officer attains the age of retirement,” Mr Kavuludi said.

“When the vacancy falls, our job is to recommend to the President. Through a competitive process, we invite applications for interviews on set criteria,” he added.

Yet the Thursday interviews could just be a manifestation of the changes that have been quietly taking place within the police service to return it under the executive’s firm grip.

“Whenever you see the President rather than Chair of NPSC or Inspector-General announcing changes in police or the entire executive arm of State presiding over the passing-out parade of officers of the National Police Service, it is a stark reminder that the concept of regime protection and protector of imperial property of the policing has not yet changed in Kenya. It is the bane of the country’s insecurity,” the executive director of International Centre for Policy and Conflict Ndung’u Wainaina says.

Through legislative changes, the Jubilee administration has systematically eroded the independence of the police service and that of the commission. The main argument for the executive taking charge has been the fight against al-Shabaab that proponents of the changes argued in Parliament needed to allow the President freedom to make changes to the security apparatus.

Articles 238, 243, 244, 245 and 246 of the 2010 Constitution establish the National Police Service with full constitutional insulation, institutional autonomy and legal amplitude to deliver on its core constitutional mandate.

POLICE REFORMS

On the other hand, the National Police Service Act 2011 provides the operating mechanics of the Service.

“The Constitution directive on police reforms sought to achieve functional autonomy for the police through security of tenure, streamlined appointment and transfer processes, and the creation of a ‘buffer body’— the NPSC — between the police and the executive and enhanced police accountability both for organisational performance and individual misconduct,” said Mr Wainaina.

However, he believes the executive has exercised hostility to this constitutional scheme.

“Predictably, the government has been dragging its feet on implementing the overhaul and comprehensive police reforms. The government is leaving no stone unturned to retain control over the police,” he said.

Through the Security Laws (Amendment) Act 2014 the Jubilee administration came out to claw back the constitutional safeguards that had been put to insulate the national police service from interference.

Through the Act, the President reclaimed the powers he had lost through the constitution and the recommendations by various task forces including the Justice Philip Ransley-led task force.

POWERS

Section 86, which was subsequently upheld by the High Court in February 2015, amended section 12 (2) of the National Police Service Act to give the President powers to “nominate a person for appointment as an Inspector-General and submit the name of the nominee to Parliament” thereby removing NPSC from the process. It also limits public participation with such participation being done indirectly through MPs.

The controversial Act also removed the security of tenure of the Inspector-General of Police and the two deputies who “may be removed before expiry of his term subject to the provisions of Article 245(7) of the Constitution.”

In effect, the Inspector-General of Police and the two deputies currently serve at the Pleasure of the President.

The independence and conduct of the police has come increasingly under scrutiny following the brutal response to opposition protests after the nullified August 8 and the repeat October 26 presidential elections.

“Kenya is not under-policed. It is badly policed. The security and law enforcement agencies are trapped in regime policing of the colonial times. This practice has been carried over by subsequent post-independence governments, including the current government.”