Why East Africa still remains a literary dwarf

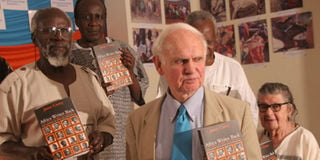

Writer James Currey (front) poses with his book Africa Writes Back together with other African writers (from left) Taban Lo Liyong, Laban Erapu, Walter Bgoya and Majorie Oludhe McGoye at the National Museums of Kenya in Nairobi. Photo/FILE

What you need to know:

None of East African writers made it to the shortlist of the 14 novels to represent Africa in the competition that brings together writers from Britain and her former colonies

East Africa, condemned in the 1960s by Taban lo Liyong as a “literary desert”, has once again registered a poor showing at the Commonwealth Writing Prize because of poor editing and over reliance on donor funding, literary critics, publishers, and novelists have observed.

Ugandan writer and director of the newly established African Writers Trust, Goretti Kyomuhendo, say that the quality of teaching in East African universities has gone down. Most writers in the 1970s and 1980s were based in universities.

None of East African writers made it to the shortlist of the 14 novels to represent Africa in the competition that brings together writers from Britain and her former colonies, including Ireland, the Caribbean, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Kenya had a few entries, which could not withstand competition from other regions of the continent. Uganda, which in the past has offered winners such as Doreen Baingana, did not submit a single book. Neither did Tanzania nor Rwanda.

“South Africa and Nigeria on the other hand submitted more than 15 books each,” says Dr Dan Ojwang of the University of the Witwatersrand, who served as a judge.

Refreshing read

Among East African entrants were An Account of the Deception of David Kyalo by Moses Kilolo, The Terrorists of the Aberdares by Ng’ang’a Mbugua, A Measure of Courage by Muroki Ndungu, Eyo by Abidemi Sanusi and That Cunning Mask by Gabby Ozems.

Though published in Kenya, Gabby Ozems is Ghanaian and the shortlisted Abidemi Sansui is Nigerian. Most of the novels from East Africa were poorly edited books about worn-out themes such as torture and suffering, commented one of the judges. The region’s writers are not as experimental as their counterparts in West Africa and South Africa.

“It looks like East Africa is still bent on the good old once-upon-a-time tale which, though well-written, might not compete well with the new trends in South African writing,” says Bob Kisiki. However, some were refreshing.

“Ng’ang’a Mbugua’s book was a charming narrative of the human-wildlife conflict in the Aberdares,” says Dr Ojwang, who represented East Africa on the panel of judges. “But it was just not substantial enough (lengthwise and in terms of complexity) to be considered for the prize, especially given the stiff competition from Nigerian and South African entries.”

Market forces

There seems to be a consensus among critics interviews by Africa Review that the major problem facing East African literature is poor editorial choices. “Publishing houses in the region have not been enthusiastic about promoting the publication of novels for instance, partly also due to the market forces that tend to favour school texts more than anything else,” says Dr Godwin Shiundu of the University of Nairobi.

Dr Ojwang seems to agree. “Henry Chakava’s good work at the helm of East African Educational Publishers has not been continued by any of the younger publishers,” he says. Bob Kisiki, an associate editor at Uganda’s Fountain Publishers notes that his country “has not paid much attention to publishing fiction, for the obvious (financial) implications involved.

It may sound tired as a reason, but when a genre/field is under-published, it’ll be under-developed, for lack of good examples to emulate.” Gems could be lying with publishers but will never see the light of day because of financial consideration in a region with lower literacy in English, especially in Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania.

“So many manuscripts are gathering dust on editors’ shelves because it would be unprofitable to publish them,” says Joseph Kajura of Fountain Publishers. Publishers are interested in older writers like Ngugi wa Thiong’o and M.G. Vassanji at the expense of younger talent, observes Dr Shiundu. “Young Nigerian writers have solid precedents in great writers like Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, and have shown greater willingness to chase overseas publishers, who generally provide better support — even if at a cost,” says Dr Ojwang.

“The local publishing scene in Nigeria, though, is struggling just like in the Kenyan case. But a larger reading public and a larger base of potential writers certainly help.” “It might not be different in other African countries,” observes Goretti Kyomuhendo, who is based in London. “Award-winning African writers, such as Doreen Baingana (Uganda), Chimamanda Adichie (Nigeria), Sade Adeniran (Nigeria), Uwem Akpan (Nigeria), Helon Habila (Nigeria) published their acclaimed works outside Africa.”

Dr Ojwang currently based in South Africa suggests that the region’s literature is dangerously relying on donor funding through NGO-based publishing. Once the funding is not available, these NGO outfits become moribund. “Uganda’s Femrite has gone strangely quiet,” he says. “Perhaps donor funding has dried up.”

Yet Prof James Ogude of the University of the Witwatersrand, who has been a judge in the past, thinks that the region and its donor partners are obsessed with materialistic development as opposed to the arts.

Culture and history

“Knowledge in East Africa has been so instrumentalised that anything that is not remotely linked to money-making or ‘development’ in the crude sense of the word is frowned upon,” says Prof Ogude. “Nigerians love money, but they cherish culture and literature more than we do.”

All is not lost. If East Africa breeds independent collectives — modelled along Kwani and StoryMoja — but which are independent of donor funding and politics, a literary revolution is likely. And the collectives have to be more explorative. So far, most of the few collectives in East Africa have so far not ventured beyond short stories.

“We are still waiting for Binyavanga Wainaina’s, Kantai Parselelo’s and Yvonne Owuor’s first novels,” says Dr Ojwang. The poor showing in the commonwealth competition does not mean that East African literature is dead. The Commonwealth Literary Prize is exclusively for work in English. Tanzania and Rwanda produce work in Kiswahili and French, respectively. The Kenyan scene is fairly active in Kiswahili and vernacular publishing, which could be a pointer to greater decolonisation of letters from British writing, around which Commonwealth literature orbits.

— The writer is a professor, English department, at the Northwestern University, US