World War 2 and memories from my father

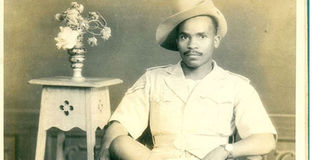

Sergeant Ngotho Kamau. During World War 2, he was a fresher in the pioneer class at Kenya Teachers College in Kiambu. PHOTO | COURTESY

What you need to know:

- Unarmed as they weren’t direct combatants, Kenyans suffered most casualties on the frontline — either from enemy fire, hunger, or disease.

- The college at Githunguri had been started by Africans in protest after realising the colonial “education” was designed to make them forever subservient to the British.

My father Ngotho Kamau was a born storyteller.

If you asked him the time, he not only told you the local time but also what time it was in London and in New York, and why the difference.

I knew from him what Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is long before I heard it from my geography teacher.

He told me why, when it is midnight on Sunday in Siberia, it is midnight Saturday in Alaska, and that DR Congo is the only African country with two time zones (western end of the DRC is one hour behind the eastern side).

Some of my father’s most favourite stories were about World War II.

The war found him a fresher in the pioneer class at Kenya Teachers College, Githunguri, in Kiambu.

He was in the lot that was forcibly enlisted in the British army when Italians, fighting on the side of the Germans, threatened to overrun the British in Kenya Colony.

CALL UP

They already had swept through Ethiopia, forcing Emperor Haile Selassie to flee to Europe, chased the British out of Somalia, and set sights on Kenya.

In panic, the British enlisted 98,240 Kenyans — my father among them — to help stop the Italians.

Here is a distillation of what I remember my old man telling me about the war.

He told me Africans weren’t keen to go to the frontline to defend the British against the Germans.

They’d done so in World War I, only for the latter, like the proverbial ass, to reward them with a kick where it hurts most.

About 50,000 Kenyans had forcibly been conscripted as carrier corps during World War I.

Their role wasn’t combat but porters to carry machine guns and pull heavy artillery to the frontline for use by British and Indian troops deployed in the campaign against the Germans, who colonised Tanganyika (Tanzania) and were keen to evict the British from Kenya.

NO PAYOUT

Unarmed as they weren’t direct combatants, Kenyans suffered most casualties on the frontline — either from enemy fire, hunger, or disease.

To add insult to injury, at the end of the war, the carrier corps were dumped at the city’s Kariokor area (the name is a corruption of “carrier corps”) and told to go home without any compensation — not even some token to help them restart life afresh!

So when Kenyans heard the Germans had returned by declaring a second war on the British, they felt it was fair game.

The thankless Brits needed a Hitler to teach them a lesson, they reasoned.

Secondly, for Kenyans — more so those living in Mount Kenya region and in the Rift Valley — the British had confiscated their best land, put them on forced labour, and demanded they pay taxes.

In a word, Kenyans had been reduced to third class citizens, if not slaves in their own country.

So what motivation would have been there for Kenyans to want to save the British “Empire”?

EDUCATION

Thirdly, for the likes of my father, enlisting in the army to save the British would have been an irony because they had enrolled at Githunguri College to get education as a first step in the journey to eventually kick out the British from Kenya.

The college at Githunguri had been started by Africans in protest after realising the colonial “education” was designed to make them forever subservient to the British.

The syllabus at the college had been designed by Kenyans in conjunction with pan-Africanists and Caribbean revolutionaries who were at the forefront of black liberation movements in the 1930s through to 1960s.

It is while at the college that my father and his colleagues discarded their English baptismal names and resolved to be “pure” Africans.

Fourthly, for my father’s generation, joining World War II was a distraction at the personal level.

In his case, he was in the final year, looking forward to a stellar career in teaching — the best Africans could have a shot at those days.

He was also engaged to a girl who would be his first wife and looking forward to start a family. A small digression if you allow me.

ABYSSINIA

My father was polygamous, with two wives. My grandfather had four. So don’t be surprised to hear yours truly is a polygamist.

I come from a clan that doesn’t subscribe to Mwai Kibaki’s doctrine of, “I have only one dear wife”.

On recruitment in 1941, my father and his lot were hurried through training at Kahawa army garrison and deployed to Abyssinia, as Ethiopia, was then called.

The Italians had just bombed a British garrison in Wajir, where major casualties were inflicted on a detachment that had been flown from Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

Next, Moyale fell to the Italians as they marched down to about one 100 kilometres inside Kenya.

Italians also heavily bombed Isiolo, a town at the centre of Kenya. The intention was to flatten the capital Nairobi but, in the absence of advanced warfare navigation, they bombed the geographically centrally placed Kenyan town of Isiolo, on the wrong assumption that it had to be the capital.

Italians also attacked from the Somalia flank, bombing El Wak and Malindi.

VULNERABLE

My father was in the brigade that entered south-western Ethiopia from the Lake Turkana front.

The other brigade, mainly made up of soldiers flown from South Africa, approached from the south-eastern side.

It is from the combat in Ethiopia — as well as in Asia where Kenyans were shipped to help the British in stopping Japanese expansion — that Kenyans saw the soft underbelly of the British.

They learnt the white man wasn’t only vulnerable, but also fearful of face-to-face combat.

My father remembered how British soldiers dreaded what they called bayonet-to-bayonet (face to face) encounter with soldiers from the Merrile community who were fighting on the side of Italians.

The British would rather face fellow mzungus (the Italians), not the battle-hardened Ethiopians.

***

Despite vulnerability of the British coming out in open, and Africans proving as good, if not better, soldiers in the battlefront, the British insisted on discriminating against African soldiers.

My father recalled a case of one Mugo wa Kimani, with whom he’d been together at Githunguri College and recruited together in the British army.

Kimani proved the best field hygiene instructor, with even senior British officers up to rank of a colonel sitting in his classes.

Yet he’d never be promoted beyond rank of a warrant officer, the highest for an African!

Even more humiliating, Africans were housed in separate quarters from the Europeans and Indians, received separate food rations, and had to wear shorts even when fighting in mosquito-prone areas!

***

Because of the unfair and shoddy treatment, my father told me, they physically fought on the side of the British but their hearts were with the Germans.

In their lone sessions, Africans soldiers would discuss with admiration exploits of German’s General Erwin Rommel, who was raining hell on the British in North Africa.

Also Africans didn’t think much of Winston Churchill, the much venerated war hero.

To the Africans, my father told me, Churchill was just a “big talker and a racist”.

If you told my father the British won World War II, he would quickly correct you that it was the Americans who won the war for the British after the Normandy Landings.

The latter was a massive deployment of US troops in Europe, which helped push back Hitler and eventually make him surrender and commit suicide.

African soldiers also didn’t think the British were good war strategists.

My father told me the several incursions where the British lost in Ethiopia and Somalia weren’t because Italians were better soldiers but because of poor planning.

DOUGLAS MACARTHUR

The Italians would retreat where they had no chance, but would return with vengeance.

To the contrary, the British would proceed to the frontline on misplaced braggadocio only to be humiliated.

On that score, my father’s hero was American General Douglas MacArthur, who on reading the writing on the wall in the Philippines, where the Americans risked to be overrun by the Japanese, called for a retreat but with the famous words: “I shall return!”

And true, the Americans did return with a force the Japanese have lived to regret.

In his old age, when confronted with a difficult situation, I often would hear my father say that when you have a river flowing in fury, the best thing to do is to stand aside and cross later rather than get drowned.

As for his hero, Gen MacArthur, I remember reading somewhere that in his old age, he had advised both President John Kennedy and later Lyndon Johnson not to go to war in Vietnam, only for their ujuaji (ego) to get the better of them … to devastating consequences!

MISTREATMENT

Just like my father and his lot had feared, the Brits misbehaved — yet again! — when the guns stopped in World War II.

While the white soldiers were handsomely rewarded, their Africans counterparts were told to go home and fend for themselves the best way they knew!

The madharau (mistreatment), as my father would put it, began in the word used for their parting. For the white soldiers, the term used was “discharge from service”.

For Africans, the term used was “demobilisation”, an insulting word in the military because it implies you have been captured and have to be demobilised and taken as a PoW (prisoner of war).

Also, the white soldiers were rewarded with huge chunks of land in the “white highlands”, the term the British used in reference to land they stole from Kenyans in central region and in the Rift Valley.

Meanwhile, African ex-soldiers found themselves dumped to destitution with no compensation, land or jobs to fall back to.

This is the frustrated lot - especially in Mount Kenya, in Nairobi, and in the Rift Valley - that ended up ventilating by joining the freedom movement — a blessing in disguise.

They ended up in the Mau Mau freedom army, while others like my father were detained for taking oaths to defy the British.

Postscript

At independence, my father and others whom he was with in the British army and later in detention camps or Mau Mau, formed a co-operative society that bought a farm in Njoro/Elburgon formerly owned by the mzungu who had been their commander during action in Ethiopia, one General W. Owen, and subdivided it among themselves.

One day in my warrior-youthfulness, I asked my father why he and his colleagues agreed to buy the farm from their former mzungu commander instead of just seizing it and telling him to pack and go back wherever he had come from.

My father explained the reasoning was that it was good for the country that nobody get land for free, or forcibly acquire it, whatever the justification. He talked of the sanctity of a title deed.

Years after my father was gone, I saw the wisdom in his words when some political demagogues demanded we vacate Rift Valley because we were “foreigners”.

Our defence was — and remains — that we have title deeds and genuine ones at that. So we’re not about to leave.