Ernestine Kiano: The minister’s wife whom Moi deported

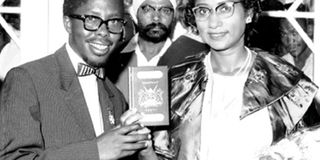

Mrs Ernestine Kiano, wife of then Commerce and Industry minister Gikonyo Kiano, proudly displays her new Kenya passport acquired in the 1960s. The Kenya Gazette notice that ordered her out of the country said she “had shown herself, by act and speech, to be disloyal and disaffected towards Kenya.” FILE PHOTO | NATION MEDIA GROUP.

Dateline: Nairobi, 1966: Cabinet minister Julius Gikonyo Kiano is having a drink at a Nairobi club. On his side is a pretty, young woman. The minister hardly notices the entry of his protective American wife, Ernestine Hammond. Furious and angry, Ernestine walks towards Dr Kiano. She removes her shoe and hurls it in his direction. He ducks. It possibly hits the wall as she creates an embarrassing scene.

While this incident is casually captured in Dr Kiano’s biography, the other story of the place of Ernestine in Kenya’s emerging story is hardly told.

After facing several other public humiliations, Dr Kiano reached out to Home Affairs minister Daniel arap Moi for help. Interestingly, Ernestine had in February 1964 become the first US citizen to renounce her citizenship.

A picture taken with Dr Kiano shows the two holding Ernestine’s new Kenyan passport inside Ruth Njiiri’s shop.

That June 4, 1966, in a Kenya Gazette notice, Moi ordered Ernestine out of the country and declared her persona non grata. Reason: “Ernestine Hammond Kiano had shown herself by act and speech to be disloyal and disaffected towards Kenya.”

Thursday June 9, she arrived at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport from London. An Associated Press correspondent reported that she looked “nervous” and, to most questions, she only said: “No comment.”

Back home, Dr Kiano did not say a word about Ernestine’s deportation. A few months later, he married a Pan African Hotel receptionist, Jane Mumbi, in a traditional African ceremony.

In most of Dr Kiano’s early 1960s photos, the dapper and diminutive Jomo Kenyatta minister for Commerce and Industry was always in the company of Ernestine.

Ernestine, a public health nurse, had arrived in Nairobi full of energy — always on tow during press conferences to light a cigarette, according to a British newspaper, for Kenya’s first PhD holder.

That Earnestine had immersed herself into both the social and political networks emerged in 1963 when she became the first black woman to hold an elective leadership position at the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA).

In Nairobi, she was regarded as Kenya’s first feminist — and as the first black woman to drive around in a Mercedes Benz. It was Ernestine who organised the first “emancipation of Kenyan woman” seminar at State House, Mombasa (then Government House) in April 1963.

The meeting was to demand more political rights for the Kenyan women.

Her best friends included Mrs Ruth Stutts Njiri, the American wife of Kanu power-broker Kariuki Njiiri — the man who agreed to forfeit his Kigumo parliamentary seat to allow Kenyatta join Parliament and attend Lancaster talks.

Ruth was also Jomo Kenyatta’s secretary at State House. Others were Margaret Gecau, Pamela Mboya, Ruth Habwe, and Mrs Jemina Gecaga — a sister of Kenyatta’s physician, Dr Njoroge Mungai.

Both Mrs Njiiri and Mrs Kiano were entrepreneurs. While Mrs Njiiri had opened a fashion store known as “Njiiris” along Government Road (now Moi Avenue), Earnestine had started a private school, Ralph Bunche Academy, named after the 1950 Nobel Prize recipient, a friend of Kianos and a UN Under-Secretary for Special Political Affairs.

Initially known as Competent Commercial College and Secondary, along Temple Lane, in down-town River Road, this business would later be sold in 1971 to Nairobi businessman Teja Singh, five years after Ernestine’s deportation.

In the rush to acquire prime properties as the settlers departed, Ernestine acquired 176 acres in Kabete. She also owned part of the land now owned by Kabete Campus and some property in Garden Estate. Again, these properties were sold by Dr Kiano in 1967 — perhaps to erase the memory of Ernestine.

In diplomatic circles, Ernestine was popular among Western ambassadors’ wives and would occasionally drop in during their private gigs as other locals kept away, according to some field staff reports compiled for the US embassy.

It was during one of those morning coffee meetings at the home of Mrs D. Sethi in Riverside Drive that Kenyans got to see the true bravery of Ernestine. As she drove out, two thieves opened the door of her Mercedes and snatched a bag containing £125.

“I gave chase and several Africans joined me but we lost them in the Chiromo estate,” she told the press.

When she arrived in Kenya, she was part of Dr Kiano’s campaign team — at times clad in Kikuyu traditional regalia.

She then believed that she could manage to organise an airlift to the US for another set of Kenya students as happened in 1960 and 1959.

K.D. Luke, a colonial adviser on the airlifts, tried to take on Ernestine for placing some students in a tiny community college hoping that they would manage to transfer to a better college. When she was asked, Luke writes in his biography, Ernestine retorted: “Well, they agreed to take them …”

It was a discussion at dinner time and Mr Luke could see Ernestine’s passion to help needy students get American education. “Mrs Kiano was obviously a remarkable and very energetic woman. She had taken over all the education aspects of her husband’s work, and no doubt she was under considerable political pressure to do this,” he wrote.

It was the team of Ruth, Kariuki, Mboya, Dr Kiano and Ernestine that worked hard to make the airlifts a success — although history of the airlifts has not been kind to the two women.

Of all the writers who have recounted the story of Dr Kiano and Ernestine, US diplomat’s wife Dorothy Stephens captured most of it in her book Kwaheri Means Goodbye: “I came to know Ernestine as an outspoken, determined woman who took no nonsense from anyone.

Tall, heavy-browed, sometimes fierce in her approach to people and problems ... she complained bitterly about their low economic status and resented the drain placed on their meagre resources by the demands of Gikonyo’s extended family and clan.”

One day, Ernestine had poured her heart out to Dorothy: “They just keep coming from Fort Hall (Murang’a) and moving in and Gikonyo refuses to send them home.” The time she was complaining about this, Dr Kiano — according to Dorothy — was living in a house that was “scantily furnished and poorly equipped, with a primitive kitchen and rudimentary stove with no oven.”

“Occasionally, Ernestine tried to give dinner parties for some of the people who had entertained them since their return to Kenya, but she was fighting against difficult odds. A few times I helped by picking up roasts or casseroles from her, cooking them in my oven, then taking them back with me to the party,” recalled Dorothy.

That Ernestine was caught in a culture clash was obvious. And it was not just her, but several of the women who returned to Kenya as wives of beneficiaries of the airlifts. “Along with the clan expectation of sharing the wealth, one of the most difficulty things for American women to accept was the attitude the men they had married had toward sexual freedom,” wrote Dorothy. “It was often the last straw for the American wives, the final intolerable act that ended the marriages.”

Dr Kiano had returned to Kenya in 1956 and, together with Ernestine, had started Competent Commercial College, occupying two floors of Consulate Chambers, off Race Course Road. They taught short-hand typing, routine office management, and English.

In Dr Kiano’s biography released posthumously by his wife Jane, she describes Ernestine as “unapologetically self-willed; she wanted her life to move by her own creed. She was also overprotective of her famous husband.”

Whether that led to the shoe incident is not clear, but a case recounted by Dorothy perhaps informs the relationship. Dorothy had one morning dropped to see Ernestine, who was expecting a baby.

“I found Ernestine home alone, in an advanced stage of labour, clutching her belly. When she hadn’t been able to reach Gikonyo, she called a taxi. It arrived just after I did, and between us, the driver and I half-carried Ernestine down the stairs into the taxi.”

The baby was delivered shortly thereafter at the hospital and Dorothy left a message to her diplomat husband Bob to use his USIS (US Investigations Services Inc) connections to trace Dr Kiano: “If you see Dr Kiano ... you can tell him he’s the father of a baby boy ...”

Dr Kiano’s Cabinet colleagues loathed Ernestine. The matter about Ernestine’s continued slighting of ministers is said to have reached President Kenyatta. But whether it was Kenyatta or Dr Kiano who asked Moi to issue the deportation order is not clear.

Dr Kiano sold the properties jointly owned by him and Ernestine. In one case, the court ruled: “If at some later date Mrs E.H. Kiano chooses to lodge any claim for that sum of money, she should do so against Dr Kiano.”

She never did and never returned to Kenya. Ernestine had four children with Dr Kiano: Curtis Kabiru, Gaylord Clinton, Damari Wanjiru and Ernest Kimani.

When Ernestine left, Dr Kiano took them to Kaptagat School in Eldoret and later brought them back to Nairobi to finish their studies. But the eldest son, Gaylord, then 15, followed his mother to the US.

The other boychild, Ernest, studied locally at Lenana School while the girls attended Kenya High School. They then left for the US where they joined their mother — the woman who had taught Dr Kiano how to dance fast jazz.

On her part, Kiano’s new wife Jane rose to become the chairperson of Maendeleo ya Wanawake organisation and is credited for building its networks nationally and for spearheading the construction of Maendeleo House in Nairobi. She is today the patron of the body.

After exiting parliament following his defeat by Kenneth Matiba in 1979, Kiano was appointed the chairman of Kenya Broadcasting Corporation. His attempts to regain his Kiharu seat were futile. He died in August 2003.