Argwings-Kodhek: The politician history should never forget

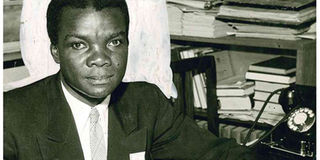

Lawyer and politician Argwings-Kodhek. In 1966, he joined the Cabinet as the Minister of Natural Resources and eventually in 1967 as Minister of State for Foreign Affairs. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- He left the Attorney-General’s chamber to start his own law firm at Church House and was the only African in Kenya with a law firm.

- Argwings-Kodhek was one of the radicals reorganising national politics alongside Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

- The formation of Kenya African National Union (Kanu) was actually an effort by Jaramogi to stop Mboya whose party was getting stronger.

When CMG Argwings-Kodhek sailed back to Kenya in 1952, he had an Irish wife whom he could not legally kiss, walk hand-in-hand in public or live together with in the same house.

Although he could afford to stay in Nairobi’s Westlands, the law did not allow blacks to live in this exclusive white suburb and neither would his wife, Ms Mavin Tate, be allowed to live with him in Nairobi’s Eastlands — then reserved for blacks only.

Until mid-1950s, the penalty for a black man who had sexual relations with a white woman was hanging, while a white male who had sexual relations with a black woman faced no penalty.

Argwings-Kodhek, in a test case on the stupidity of the segregation laws, went to court — and fought for the rights of a married couple to live together. He won.

Tuesday this week will mark the 50th anniversary of the January 29, 1969 death of Kenya’s first indigenous lawyer — the man who some thought would rise to become President.

EDUCATION

CMG, as he was fondly known, stood for “Chiedo Mor Gem” (loosely translated to mean “frying oil of Gem” or “oil of Gem”) and his baptismal names Clement Michael George.

Today, little is known about Argwings-Kodhek and history seems to have forgotten the story of the University of Wales graduate who kept the colonialists at bay from 1955 — at a time when London wanted to delay Kenya’s independence.

History has not been kind to Argwings-Kodhek and, apart from a road in Nairobi named in his honour, there is little else to commemorate his contribution — even on the emergence of an indigenous bar where he inspired a whole generation of lawyers.

Born in 1923, Argwings-Kodhek was sent to a local mission school and later to St Mary’s School, Yala, and St Mary’s College in Kisubi, Uganda, where he sat his Cambridge School Certificate in 1936.

In 1937, he enrolled at Makerere University College in Uganda where he graduated with a teaching degree in 1940.

He would then spend some years teaching in then Nyanza and Rift Valley provinces.

LAW DEGREE

His journey of defiance would start in 1947 when he was awarded a government scholarship to study social sciences at the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire, now Cardiff University.

By then, the colonial government was not allowing Africans to study law — opting to give scholarships for education degrees.

Thus, when Argwings-Kodhek applied to the colonial government to be allowed to study law, the request was turned down.

But a determined Argwings-Kodhek enrolled for a law degree alongside his sanctioned Bachelors of Arts and obtained the former in 1949 and another in social sciences.

In 1951, he became a member of the bar at Lincoln’s Inn, London — one of the four prestigious professional bodies in England and Wales.

His graduation with a law degree coincided with a time when Jomo Kenyatta had started a whirlwind tour and popularising the Kenya African Union (Kau) with demands for independence and universal suffrage within three years.

ULTIMATUM

Ultimatums had been issued and in 1951, Kau — especially its radical wing — had asked Peter Mbiyu Koinange and Achieng Oneko to carry a last appeal to Britain for constitutional changes.

Without these, the radicals had warned, there would be no compromise, but war.

Nairobi had just been elevated to a city by King George VI and the settlers were demanding sterner action against the militants.

More so, the government had expanded its intelligence and security services — with Governor Sir Phillip Mitchell seeing no need for a ban on Kau activities.

Instead, he had started a crackdown on supporters of Kenya Land and Freedom Army (also known as Mau Mau) just before he retired in June 1952.

Argwings-Kodhek would have stayed in London as a well-paid lawyer but he surprised his colleagues when he opted to return to a country on the verge of political explosion.

STATE OF EMERGENCY

By September 1952, the courts had jailed more than 500 Mau Mau supporters, most with no legal representation, and in October 7, 1952, the militants had shot dead senior chief Waruhiu Kung’u giving the new governor Sir Evelyn Baring an excuse to declare a state of emergency.

“Almost single-handedly, Argwings-Kodhek took on the formidable challenge of defending the rights of ordinary Kenyans during this critical period,” wrote historian Bethuel Ogot.

“He argued that human rights are indivisible and universal and that freedom cannot be appropriate in the West and inapplicable in Africa.”

This was the Kenya that Argwings-Kodhek flew into in 1952 — determined to give all those arrested legal help.

At first, he had sought employment at the Attorney-General’s chamber but was given a salary which was a third of what Europeans in the same grade were getting.

He protested and left to start his own law firm at Church House and was the only African in Kenya with a law firm.

POLITICS

It was here he would earn accolades for defending Mau Mau cases — saving many, including Waruru Kanja, from the hangman’s noose.

As the sole African criminal lawyer, he made it his duty to defend the Mau Mau, and he did it with gusto traversing Nairobi and Central Kenya courts to the chagrin of colonial settlers and the establishment.

The Western media hated him too and dubbed him the “Mau Mau lawyer” — which was supposed to be demeaning.

Shortly after the 1953 Lari Massacre, in which 150 loyalists, including Chief Luka Kahangara, were killed, Argwings-Kodhek helped 48 of those charged to successfully appeal on a legal technicality.

It was in politics that he would emerge as a radical voice taking on Tom Mboya, an emerging trade unionist who had support of the West, for the control of Nairobi politics.

With most of the senior politicians who were the bedrock of Kau behind bars, Argwings-Kodhek was one of the radicals reorganising national politics alongside Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

TOM MBOYA

Between 1953 and 1956 there was a ban on African political organisation, but when the Lyttelton Constitution allowed for an increased African representation, the government allowed the formation of District-based political parties — except in the Mt Kenya region.

This saw Argwings-Kodhek form the Kenya African National Congress but the government refused to register the name until he changed it to Nairobi District African Congress.

He would say that he formed the party to stop Mboya and “and his American allies”. “The Americans are not Mboya’s friends, they are his masters,” he often said.

For the Nairobi seat, Argwings-Kodhek had to fight it out with Mboya who had formed People’s Convention Party (PCP).

In his campaigns, Mboya would describe European women as “Africans public enemy number one” in reference to Argwing-Kodhek’s Irish wife.

Mboya had an upper hand, thanks to his trade-union connections and since most Kikuyu were not allowed to vote, he beat Argwings-Kodhek by a paltry 395 votes.

KANU

On one occasion as Mboya was returning from Liberia, he met a huge crowd of Argwings-Kodhek’s supporters waving placards on his face.

As Mboya stepped out of the airport towards a waiting taxi, six banners were unravelled reading: “We don’t want your speeches or underground lies, even Americans know what you are.”

The formation of Kenya African National Union (Kanu) was actually an effort by Jaramogi to stop Mboya whose party was getting stronger.

It was at the house of Julius Gikonyo Kiano in Riruta, Nairobi, that a meeting was called for all elected leaders in 1960 to launch one national party.

The meeting, called by Jaramogi, had agreed that they would register Uhuru Party. The name was later changed to Kanu.

The reason the May 1960 meeting held in Limuru was that the rivalry between Mboya’s PCP and Argwings-Kodhek’s party would turn bloody.

US FACTOR

The two had outsmarted everyone else in Nairobi politics and Jaramogi’s fear was about Mboya’s American links.

As he would later write in his autobiography, Mboya “was interested in his own ascendancy to power” by using his “unlimited supplies of foreign money”.

To tame his rival’s influence, the Jaramogi camp blocked Mboya’s would-be father-in-law and respected elder Walter Odede from running for the Central Nyanza open seat on a Kanu ticket and instead nominated Argwings-Kodhek.

While Argwings-Kodhek won the seat and went on to become MP for Gem in independent Kenya, his critics thought he was Jaramogi’s “puppet”.

He was one of the Kanu legal minds at the Lancaster conference.

CABINET

When the Hola massacre occurred, it was Argwings-Kodhek who used his British friends to raise the matter in international papers, a largely forgotten significant move.

It was his wit, intelligence and eloquence in Parliament that won him admirers. In 1963, President Kenyatta appointed Argwings-Kodhek an assistant minister for Defence.

In 1966, he joined the Cabinet as the Minister of Natural Resources and eventually in 1967 as Minister of State for Foreign Affairs.

In the midst of these, Argwings-Kodhek divorced his Irish wife and married Joan Omondo.

On January 29, 1969 he died in a mysterious road accident along today’s Argwings-Kodhek Road in Nairobi.

For just a short period at the courtroom and in politics — CMG had no match. He is one man history should not forget.

[email protected] @johnkamau1