Why we need online state critics more than a tired Cord

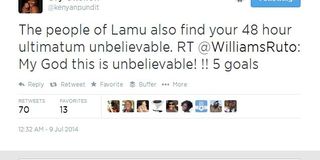

Source: kenyanpundit/twitter

What you need to know:

- Social media commentators are important for two reasons. They will not change Kenya by tweets alone but their work fills a gap left by the pacification of Parliament, demise of investigative journalism and the absence of research sponsored by civil societies.

- Kenyans interested in punchy, informed counterattacks to state policy have become accustomed to looking at Twitter or Facebook rather than to the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (Cord).

On Wednesday, this newspaper reported that the Director of Public Communications had introduced a new hashtag #StopHatespeechKenya. Ms Mary Ombara’s sentiment is (of course) unimpeachable. Who wouldn’t want to stop hate speech?

Nevertheless, her announcement was absurd. The power to stop hate speech lies with the government and not through censorship or regulation. If some of the many reforms and policies agreed as possible solutions to ethnic violence over the past 20 years could be maintained, then hate speech would be less of a concern.

#StopHatespeechKenya is one example among many of the government confusing a social media hashtag or soundbite for policy.

Moreover, it is an expression of a typical misapprehension about Twitter that mistakes online debate for political action. Even if it were to catch on, after a few weeks the hashtag would follow the ‘Bring Back Our Girls’ and ‘Kony 2012’ campaigns into oblivion.

But for every example of the banality of social media, each week in Kenyan politics throws up many instances of the potential power of Twitter.

For all the complaints by the likes of Ms Ombara about the potential for hate speech, Twitter has become one of the few arenas in which the government meets sustained and informed criticism. Its value as an all-too-rare forum for open, unrestricted debate far outstrips its capacity for becoming a place for prejudice.

Followers of Ory Okolloh have been accustomed to her ability to switch between discussion of football and the nuances of Kenyan politics. It was no surprise therefore to see her timeline during Tuesday’s World Cup semi-final alternate between posts about Brazil’s humiliation and reports of violence in Tana River county.

Ms Okolloh’s timeline quickly filled with links to relevant news reports and sections of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission’s report on Kipini. Historic land grievances, insight into current disputes in the county and discussion on the effects of mining were aggregated and analysed systematically. She was writing the first draft of history – 140 characters at a time.

Ms Okolloh is the best known Kenyan politics commentator on Twitter but she is not alone. Mr Boniface Mwangi and other politically engaged individuals are also attempting to hold leaders of all parties to account.

Social media commentators are important for two reasons. They will not change Kenya by tweets alone but their work fills a gap left by the pacification of Parliament, demise of investigative journalism and the absence of research sponsored by civil societies.

DISREGARD FOR EVIDENCE

When trying to write a chapter on violence in the 1990s, I drew on parliamentary inquiries, bulletins produced by the National Council of Churches of Kenya and articles in the Nairobi Law Monthly. Clergy, activists, politicians and professionals documented the abuses of the Moi regime.

A similar set of sources is not readily available today. For whatever reasons, newspapers and broadcasters are reluctant to be combative with government and the capacity of civil society to investigate atrocities and abuses is much reduced.

Even from a distance at her home in South Africa, by pointing readers towards important sources available online, Ms Okolloh and others like her are performing a vital service to our democracy through Twitter.

Moreover, perhaps unwittingly, the insistence that critiques of the government be substantiated with accessible sources stands in stark contrast to the government’s own disregard for evidence, namely the records about President Kenyatta’s finances and communications requested by the International Criminal Court.

The second value of the work of Ms Okolloh and other online government critics is that they are making up for some of the shortcomings of the opposition.

Kenyans interested in punchy, informed counterattacks to state policy have become accustomed to looking at Twitter or Facebook rather than to the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (Cord).

Saba Saba has done little to revitalise a moribund opposition.

In the days leading up to Monday’s rally, much was made of the similarities between the protests against the Kanu regime in 1990.

But the differences are far more telling. Saba Saba 2014 was a party rally not a demonstration by a broad alliance of politicians, human rights activists and clergy. Yet it is precisely that breadth that Cord needs to appeal to if it is to challenge Jubilee in 2017.

The opposition hopes that the new 13-point agenda marks something of a renaissance but that is highly unlikely. In contrast to the youthful energy of online debate, Cord’s leadership is tired and familiar.

The value of Kenya’s online commentators will remain undiminished so long as the country has a government that introduces a hashtag to counter hate speech rather than addressing the underlying causes of ethnic violence and an opposition that is unable to build consensus.

Prof Branch teaches history and politics at Warwick University, UK. [email protected]