How KMC’s dalliance with hubris became a blessing for Kirima

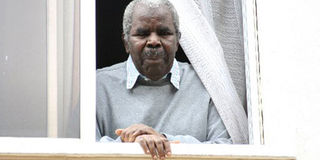

Former Assistant Minister Gerishon Kirima looks outside his house in Kitisuru, Nairobi on August 7, 2010. PHOTO | SULEIMAN MBATIAH | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Any attempts to revive Kenya Meat Commission without addressing Gerishon Kamau Kirima's vision of supplying to lower-end market will come to naught.

When the Budget was read this month, the government once again promised to pour hundreds of millions of shillings into the moribund Kenya Meat Commission (KMC), a dead relic that no one wants to cremate.

The story of the Nairobi-butcher-turned-entrepreneur who gave KMC a run to its deathbed is usually hidden in history, mainly because it is the story of a creepy monopoly that didn’t see the folly of its hubris.

The late Nairobi billionaire Gerishon Kamau Kirima, the father of nyama choma in Nairobi, is the man who asked President Jomo Kenyatta to be allowed to give KMC some competition as chairman of African Butchers Association, which later became Kenya National Butchers Union.

As the government sinks more millions into KMC, those who know how its death came about would have wished for a final post-mortem and burial.

Set up during the colonial days to serve the big farmers and provide elite settlers with choice cuts, KMC’s prime backers included then Agriculture ministers Bruce Mackenzie, Michael Blundell and his conventional right-wing successor Sir Wilfrid Havelock.

With this white market, enough to sustain it, and some export demands, KMC disregarded the African populace. Even as Kenya got independence, KMC continued to operate with colonial pomposity; nay conceit and never saw the market organise itself around a new class of African-owned butcheries and an emerging middle-class.

Kirima started to organise the Nairobi African-run butcheries—and as he got more frustrated with limited supplies from KMC, he continued to pressurise the Kenyatta government to open the abbatoirs market to new competitors. At night, his members would sneak in pirate meat from backyard abattoirs that had emerged in Kiambu and Murang’a to supply Nairobi’s growing population.

Kirima was not a butcher. He had arrived in Nairobi as a carpenter at the Royal College (now University of Nairobi) and opened a small workshop in Bahati and later in Kaloleni where his first wife, Agnes, would attend to customers as she brought up the children. He was parsimonious, albeit thrifty, with the little money he earned and he opened his first bar and butchery in Eastlands—a thriving nyama choma den.

KMC would not sell him high quality meat and like other “African locations”, as Eastlands and other estates inhabited by locals were generally known, Kirima only bought what was identified in KMC parlance as FAQ; meaning fairly average quality. This was low quality meat only fit for roasting. It would be anything from hooves to offal meat and butcheries had their separate quota which was not guaranteed at a time that KMC was the only licensed supplier of meat in Nairobi.

For this, Kirima emerged as the activist; taking on KMC to supply the butchers with their orders. But KMC, having slipped into an obnoxious miasma of self-importance, did not budge. It continued to sell high quality meat to upmarket butcheries in the City Centre, Westlands, Lavington and Mombasa.

By this time, the price of meat was government-controlled which curtailed the development of the industry.

With the frustrations he faced from KMC, even as he expanded his butcheries, Kirima invested in the transport industry by registering his own bus company competing with Dedan Njoroge Nduati’s Jogoo Kimakia Bus Service as the two leading African-owned bus companies in Kenya against established British company Overseas Trading Company (OTC) on the central Kenya route. But Kirima Bus Company Limited did not survive for long after Kenyatta issued a decree that allowed matatus to run transport business from Nairobi to other towns in 1973. Kirima and other transport entrepreneurs: Muhuri Muchiri, Tom Mboya, and Nduati were some of the first casualties.

The Murang’a-born baron turned to Kenyatta for help. Kenyatta told him that if he thought matatus were making more money, he should sell the buses and invest in matatus. He folded his Kirima Bus Company and returned to Kenyatta with another request: He wanted the KMC monopoly quashed and the ban on the sale of meat within the city from African-owned abattoirs lifted. Kenyatta agreed and that is how Kirima built his own abattoir in Njiru, Nairobi, where he owned a 500 acre ranch he had purchased in 1967 from an Italian farmer Donenico Masi. He had also bought two large farms in Nairobi which included some 108 acres from British settler Charles Case and a further 472 acres from Percy Randall, the settler who had sold most of his land to Magana Kenyatta in 1967. With such land, Kirima established himself as a rancher keeping beef animals and supplying Nairobi with meat via the frustrating KMC.

But even with the riches, he remained true to his rural roots. His children would still pick coffee in his farms, go around Nairobi collecting rent, and sell meat in their spare time.

With his Njiru Abattoir and another one in Dagoretti, KMC was in effect running a fake monopoly, just like the Kenya Bus Service with the entry of matatus into the business.

Established by a colonial outfit, Kenya National Farmers Union, KMC had started business by disregarding African livestock owners arguing that they did not have export market steers. By only getting its supplies from white-owned ranches, KMC had a strict structure that few locals could penetrate.

Just before independence, there were calls to have producers have a say on the running of the commission and buy shares in the enterprise. This was shot down by Minister Sir Wilfrid Havelock, who wanted to have an up-market meat parastatal. Some carcass brokers had also coalesced around African Livestock Marketing Organisation (AMLO), which not only dictated prices but had final say on whether they could purchase any steer from an African farmer. Since almost all Africans had no license to directly supply livestock to KMC, they relied on these brokers and that is how African butchers under Kirima ganged up against the KMC and pushed to start their own abattoirs.

As KMC marketed its “up-market” beef, the Kirima group snatched the growing lower end market and promoted the consumption of roast meat in order to build a viable meat industry.

Because of that, he became the love of many Nairobi dwellers and his Kirima butcheries were famous for beer and nyama choma. He not only became a Nairobi Deputy Mayor, despite his primary education, but was also elected an MP in Nairobi’s Starehe.

As he lived, he was one of Kenya’s inconspicuous billionaires; frugal to a fault. In his later years, before he started ailing and after falling out of politics, he would always be seen around some cheap restaurants around his Kirima building, near Jeevanjee Gardens, taking sugarless tea with mandazi.

On one occasion, he left Kony Pot restaurant protesting that Sh80 was too much for a cup of tea!

Still, he would walk into Barclays Bank’s Market Branch, where he had an account, carrying a bag full of the rent cash collected from his buildings – which according to court succession documents brought in more than Sh20 million a month.

The Kirima drama that preceded and followed his death exposed the other side of this rags-to-riches businessman, who had invested in real estate by taking advantage of the opportunities that came with the expanding African middle class in 1960s and 70s, eclipsed the story of KMC and his contribution to the growth of the sector. Unlike other flashy millionaires, who always want to look smart at parties and drive top-of-the-range cars, Kirima was rudimental, wedged between his underprivileged past and an uncanny well-heeled lifestyle that he never embraced.

By the time he died on December 21, 2010 in Sandton, South Africa while on treatment, Kirima and his family were the centre of media attention as members openly fought for the control of his multi-million real estate empire and other investments.

It was a drama that had all the tenets of a Mexican soap opera: charms, cash, witchcraft, back-stabbing, and litigation.

Kirima hardly controlled the drama. Ailing and having lost one eye due to diabetes, Kirima’s remaining eye had only 40 per cent vision. As such, he was more of a spectator, — thanks to his old age – and as the diabetic condition he had battled for over 40 years took a toll on him.

A simple man whose love for v-necked sweaters worn under a suit was legendary, Kirima’s public stance belied his business acumen and wealth, but revealed his modest background. In life, he avoided the sophistry associated with millionaires and was eulogised as a “scrupulous… honest (and a) gentleman”.

Because of his little formal education, having dropped out of school at an early age, Kirima opted to run his businesses based on trust, with his sons, daughters, and first wife providing the necessary labour in the farms and collecting rent income. At best he only trusted himself.

Like many businesses registered in the early 1960s, at a time when women didn’t inherit property, his empire was masculine Kirima and Sons Ltd, exemplifying the weaknesses of the social structure that he was moulded into.

Like many of his age-mates who did not go beyond basic education, Kirima’s background was weaved around the colonial education structure that prepared Africans for menial jobs. But with that, he organised an industry that finally brought down KMC. Any attempts to revive it without addressing the Kirima vision of supplying to lower-end market will come to naught.

Kamau is acting editor, investigations and special projects; [email protected]; @johnkamau1.