Messy politics – the legacy of Moi’s rule

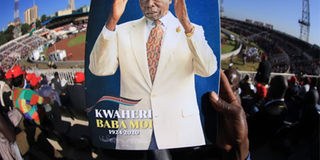

A portrait of former President Daniel Moi displayed at Nyayo National Stadium on February 11, 2020. PHOTO | SILA KIPLAGAT | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Immediately after Moi assumed office in 1978, he realised that he lacked both resources and trusted group of elites which he could use to consolidate political power.

- Keen to develop new politicians, he designed a strategy of ‘moulding’ individuals, adopting them to pursue a mission to undermine opponents, disengaging them after the mission, and re-adopting them for another purpose.

- The practice of playing off politicians against each other, and using illiterate power brokers to bring down influential individuals laid a foundation for bad practice of politics.

- The imbalances in development arising from how Moi practiced politics and how he distributed development resources have been responsible for political conflicts in Kenya.

The praise songs and chants that dominated the funeral of former President Daniel arap Moi prevented a clear reflection on his legacy. It did not allow a reflection on what his 24 years of leadership did to Kenya’s politics and development. Yet his style of leadership left behind destructive marks wherever he went and on whoever he decided to punish, rebuke or reward. His approach to politics was informed by the need to punish the small but very powerful group of Kiambu elites who had mistreated him at every turn when he was the Vice President to Kenya’s first President, Jomo Kenyatta. But what appeared as a strategy to punish the Kiambu elites was later applied to politicians and politics across the country including in his own home base, the Rift Valley.

It all started immediately after he assumed office in 1978 when he realised that he lacked both resources and trusted group of elites which he could use to consolidate political power. He did not trust those in office because many were contemptuous of him. He had therefore to look for a new crop of leaders.

Keen to develop new politicians, he designed a strategy of ‘moulding’ individuals, adopting them to pursue a mission to undermine opponents, disengaging them after the mission, and re-adopting them for another purpose. In this strategy, Moi would identify an individual, give them bundles of money for use in harambees where they would attack critics of Moi, and then get them off once the mission was accomplished. Once the mission was accomplished, Moi would dump the individual and look for someone else to use. By the mid-1990s, Moi had perfected this strategy of ‘personality engagement, disengagement and recycling’ so well that it had become easy to predict on what would happen to any individual politician picked to run a dirty mission – use, dump, recycle, and dump again.

Some of the first districts where this strategy was employed included Kiambu and Siaya. By the end of the 1970s when he came to power, these two were some of the politically central and influential districts in the country. Kiambu was home to the first President and many of the most powerful individuals who surrounded him. Siaya was home to the first Vice President of Kenya, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, and some of Kenya’s most progressive and radical politicians came from the district. By the mid-1990s both Kiambu and Siaya were some of the most marginal districts in terms of politics in the country. Their power and influence had been systematically broken and their political leadership and influence completely neutralised.

Creating and dumping politicians

In Kiambu, for instance, to break the dominance and the influence of the elites associated with Jomo Kenyatta, Moi intervened to created new individuals including Arthur Magugu who served as a Minister for Finance. He gave these individuals unlimited funds for use in harambees so that they could entrench themselves and replace the old networks that were hostile to Moi. Magugu, however, was not effective enough. This resulted in Moi disengaging him and picking a new person to run the mission. He picked former University of Nairobi Vice Chancellor, Josphat Karanja, adopted him, and even appointed him the Vice President. Again Karanja failed to deliver and had to be dumped.

Politicians were usually dumped in a very painful and humiliating manner. For Karanja and others in Kiambu, Moi picked a virtuously unknown government motor mechanic, Kuria Kanyingi, to run the mission of humiliating these politicians. He was also given enough resources – bundles of harambee money to donate to churches, schools, and women self-help groups, not only in Kiambu but elsewhere in the country. From a motor mechanic, Kuria Kanyingi, became a leading patron of local schools and development projects in different parts of Kiambu. Politicians from other parts of the country would call on him as a guest so that they could access his money – funds given by Moi for these missions. They also wanted to associate with him because they knew he was close to Moi.

Other districts had their equivalent of Kuria Kanyingi and a majority of these ‘equivalents’ were also uneducated – illiterate politicians. They included Machakos Kanu Chairman, Mulu Mutisya; the Baringo Town Council Chairman, Philemon Chelagat; Nakuru Kanu chairman, Kariuki Chotara, etc. They too, like Kuria Kanyingi, had access to unlimited amount of money which they would use to ‘destroy’ politicians who were opposed to Moi.

To give them an advantage over others, Moi revitalised Kanu which was a ‘dead’ party at the time he came to power. Moi called for district party elections during which his anointed supporters would be elected party leaders. Alongside the party, he also strengthened the Provincial Administration and gave chiefs enormous powers at the local level.

Moi handed over the party and the provincial administration to these group of loyalists to use as a tool to silence critics as well as to accumulate wealth using different approaches. In addition, Moi began to play off ethnic groups against each other. He would also upgrade some groups at the expense of others. At the same time, individual politicians were played off against each other in a manner that undermined their ability to carry out their representation roles. Fist fights between politicians from the same region were quite common in Parliament in this regard as individuals sought to outcompete one another.

This practice of playing off politicians against each other, and using illiterate power brokers to bring down influential individuals laid a foundation for bad practice of politics. Individual politicians now began to serve the purpose of representing Moi’s interests rather than the interests of the communities they represented.

Use of state money for harambee undermined local development

This approach, in addition, undermined local development processes. Moi’s approach to politics destroyed local development in many ways. Harambee fund raising events were converted into a platform for destructive politics. It was in Harambee meetings that these politicians would attack others while contributing their harambee funds. The traditional meaning of Kenya’s harambee became diluted and completely taken off the course by Moi and his new politicians. Every weekend, they would come with money and ‘pour’ it on district projects which had little benefit to the local people. In turn, people would not associate themselves with these projects; they would see them as Moi’s or would name the project after the local politician who brought the funds.

Moi’s practice of politics had a destructive effect on other institutions of development. In 1983, he introduced District Focus for Rural Development (DFRD). This was a new blue print meant to enable people participate in making decisions on their development priorities. However, in the end it served a different purpose. It became a tool to punish areas that were opposed to the President and the ruling party. Powerful party chairmen would get resources for their projects even without attending District Development Committee (DDC) meetings where resources were shared. A simple telephone call to the Chair of the Committee was enough to award the funds. And if the Chair of the DDC for any reason behaved in a manner to suggest that the matter had to be discussed at the Committee level, then Kanu officials (many of them illiterate) would just punish him or seek his transfer away from the area. Secondly, this new approach to development gave Moi an opportunity to re-visit the idea of regional focused development which was central to the Majimbo regional governments in the 1060s. The new approach and domination of the Committees by Kanu allies resulted in imbalances in distribution of development resources. Those areas that supported Moi ended up with relatively more development projects and services than those opposed to him.

The imbalances in development arising from how Moi practiced politics and how he distributed development resources have been responsible for political conflicts in Kenya. The game of playing off politicians against each other has not been perfected by those who learnt this from him. But the legacy of using state money in harambee events and converting harambee initiatives into a platform for fighting opponents has had the most destructive impact in Kenya today. It destroyed the spirit of pulling together.

Prof Karuti Kanyinga is based at the Institute for Development Studies (IDS), University of Nairobi.