The peculiar way Kenyans use English

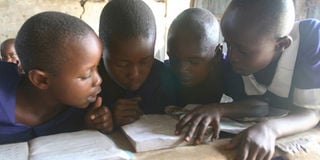

Pupils reading in class. If you look more closely at our writing and our speech patterns, you would see that there are in fact striking peculiarities about the way we use English. FILE PHOTO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

If you look more closely at our writing (and our speech patterns), you would see that there are in fact striking peculiarities about our language.

If “Black Kenyan English” is recognised by language experts as the lingo of a specific group of people in a particular area of the world — a dialect with its own (unwritten) grammar rules — do purists, including newspaper editors, have a right to impose on its speakers the rules of Standard English?

- People who edit newspapers, in contrast, tend to be obsessive about how language is used, because they believe that clear and correct expression is at the core of how they earn their credibility.

If you don’t spend your waking hours studying the various ways the English language is used around the world, you may find it hard to accept that there’s such a thing as “Black Kenyan English”.

That’s supposedly a dialect distinct from other Kenyan “Englishes,” with its own conventions and (unwritten) grammar rules.

The website of the Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies at the University of Freiburg in Germany describes Kenyan English as “a post-colonial second language variety spoken by Black Kenyans”.

“It co-exists with minority native English varieties spoken by White and Asian Kenyans,” the site adds. (I've never thought of myself as a “Black Kenyan”, but that’s a separate subject.)

The Freiburg researchers’ description is the only instance I've seen so far of an explicit distinction being made between so-called Black Kenyan English and other local varieties.

SPEECH PATTERNS

Of course, on reflection, the distinction makes sense. It’s a subject that preoccupies some of us who edit copy for Nation.co.ke.

If you look more closely at our writing (and our speech patterns), you would see that there are in fact striking peculiarities about our language.

For me, the most noticeable and most interesting feature of our dialect is our tendency to drop the definite article (“the”) from the sentences we produce — even in our professional writing.

The Freiburg researchers tag this feature “pervasive or obligatory,” and provide some samples: “Ideal candidate will be a recently qualified accountant…", “Deadline is next month …”, “Women Enterprise Fund…”, etc.

But you don’t need Freiburg to tell you all this. Just read official reports, listen to our politicians or inspect any random page of your favourite daily newspaper.

The most charitable analysis I’ve heard offered to explain the peculiar way in which we use English is that our variety of English is influenced by our native languages, which most of us learn first before we are introduced to English in primary school.

SECOND LANGUAGE

Unlike English, the reasoning goes, my Bantu language supposedly doesn’t need articles (“the” and “a”). When using English, I’m assumed to think in my native tongue before translating the thoughts and expressing them in my second language.

As a result, the theory goes, my brain is conditioned to tell my mouth (and my hand) to skip the English article as superfluous.

Another analysis is less forgiving: We have bad English teachers and we don’t bother to continue studying the language once we leave school.

These observations prompt three related philosophical questions. First, should the absence of “the” in certain places in our sentences where a native or near-native speaker would apply one be deemed a grammatical error?

For someone editing any of Nation Media Group’s publications and websites, the answer would presumably be yes, because the language of the outlets — whose principal audience is Kenya’s educated classes — is assumed to be Standard English, the other variety of English known to be spoken in Kenya.

Second, if “Black Kenyan English” is recognised by language experts as the lingo of a specific group of people in a particular area of the world — a dialect with its own (unwritten) grammar rules — do purists, including newspaper editors, have a right to impose on its speakers the rules of Standard English?

LANGUAGE POSTURE

Third, should this dialect be acceptable in formal writing — in serious journalism, in academic writing, in books?

The answers to the last two questions ultimately depend on a person’s posture about language.

When I took linguistics classes at an American university, one professor (who described herself as a “morphologist”) routinely expressed contempt for “prescriptive grammar” or traditional grammar and its rules.

The professor’s view was that what matters is the way users of a particular language or dialect speak it now (also called “descriptive grammar”).

But a professor’s credibility doesn’t grow from his or her mastery of English grammar (exhibit 1: articles in academic journals).

People who edit serious newspapers and websites, in contrast, tend to be obsessive about how language is used, because they believe that clear and correct expression is at the core of how they earn their credibility. Readers can see that here at Nation.co.ke there is an enduring clash between "Black Kenyan English" and Standard English.

Mr Gekonde is a Nation online sub-editor. [email protected].