Moi, Nyayoism and spread of dictatorship and corruption

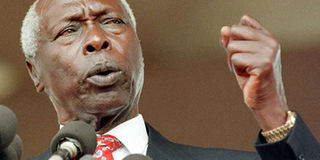

Retired President Daniel arap Moi. Mr Moi never committed to eradicating corruption. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Under President Moi Parliament did not solve problems. Instead of being a tool of liberation, it was an instrument of dictatorship.

- The Kikuyu elite’s presumption Mr Moi would favour them while in power benefited Mr Moi, whose government they were willing to tolerate and exploit.

I came to know retired President Daniel arap Moi rather closely when he sent me best wishes in the 1974 polls, not directly but through a Mr Kiptanui – a prominent Nakuru businessman.

Mr Moi, then an embattled vice president, had taken an interest in me because we were both underdogs in the Gikuyu, Embu, and Meru Association politics of the day.

The next elections were rigged and I was detained without trial after the assassination of Nyandarua North MP Josiah Mwangi (JM) Kariuki in 1975. I was a young lad then.

After being released from detention in December 1978, I met Mr Moi once again at a function called by Mr Kenneth Matiba and attended by Finance Minister Mwai Kibaki and Laikipia MP Godfrey Gitahi (GG) Kariuki – then a powerful team.

They asked me whether I was still interested in the Nakuru North parliamentary seat, which was held by Mr Kihika Kimani.

ONE-PARTY STATE

I told them that I was and they assured me that there would be no rigging.

After I won the 1979 election GG Kariuki, who emerged as a powerful figure in the first years of Mr Moi’s presidency, invited me to his home and offered me a Cabinet position.

I accepted but asked to be a backbencher for a year to raise questions in Parliament for my Nakuru North constituents.

But after one year, I became disillusioned with Mr Moi’s one-party dictatorship.

Shortly after the elections, Mr Moi invited me and my wife to his Kabarak home where we had a sumptuous breakfast.

He then asked me to stop raising land issues in Parliament because the government had no land to give to the poor.

LAND REFORMS

He said the only land available belonged to the Kikuyu and Kalenjin elite and he could not take it from them.

I told Mr Moi that land was one reason Kenyans fought for independence and failure to give it to poor people could make his government more unpopular than the colonial administration.

Instead of Mr Moi agreeing to be Joshua and lead his people out of Egypt (poverty and other ills), he warned me against calling for land reforms.

By the time the regime lost elections in 2002, it was more unpopular than the colonial government.

It became clear that he had no ambition to lead Kenya from the Third World to the First World.

Mr Moi’s ambition, as that of President Jomo Kenyatta before him and Mwai Kibaki and Uhuru Kenyatta after him, was to benefit a few while leaving the majority in abject poverty.

JOURNALISM

I realised that under President Kenyatta, we had won not independence with democracy, but self-rule without freedom.

Earlier, when I returned to Kenya after studies at Cornell University in the US and considered where to start the struggle for democracy, I chose journalism.

And although Kenyan leaders bragged of being democratic, when I exposed real problems in a weekend column of the Sunday Post, the police paid me a visit and I was detained without trial.

Later, the Sunday Post was bankrupted through over-taxation and JM Kariuki assassinated – it became clear to me that I would never give up on fighting for poor people.

I had to go to Parliament to do this. Then I was detained. While in detention Mr Kenyatta died and Mr Moi became president.

Although he protected me against rigging in the 1979 polls, I became convinced that rather than becoming our saviour, he would be our oppressor.

AUTOCRACY

Under President Moi Parliament did not solve problems. Instead of being a tool of liberation, it was an instrument of dictatorship.

I was under more tyranny as an MP than I was as an ordinary person. Police trailed me wherever I went. Citizens and their leaders were scared.

I have never seen more scared MPs than when Parliament was changing the Constitution to make Kenya a one-party state in 1982.

Threatened with detention without trial, MPs choked with fear. Surprisingly, when I was detained, I heaved a sigh of relief. I was more free in detention than as an MP in the outside world.

Under the one-party State, freedom of expression was muzzled from September 1984 when Mr Moi demanded:

“I call on all ministers, assistant ministers and every other person to sing like parrots. During Mzee Kenyatta’s period I persistently sang the Kenyatta tune until people said, ‘This fellow has nothing to say, except to sing for Kenyatta’. I said: 'I did not have ideas of my own. Why was I to have my own ideas?' “I was in Kenyatta’s shoes and, therefore, I had to sing whatever Kenyatta wanted. If I had sung another song, do you think Kenyatta would have left me alone? Therefore, you ought to sing the song I sing. If I put a full stop, you should put a full stop. This is how the country will move forward. The day you become a big person you will have the liberty to sing your own song and everybody will sing it.”

GROWTH SLUMP

After the declaration the economy went into a free-fall. How can people without a voice develop?

Mr Moi never committed to eradicating corruption. When I was elected chair of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC), he demanded my immediate resignation or he would dissolve the committee.

He falsely claimed that as chair of PAC I would witch-hunt civil servants. But I refused to resign because the accusation was baseless.

I had absolutely no intention to victimise anyone against whom there was no evidence of corruption.

Mr Moi had no problem with corruption. He never questioned the Ndegwa Commission report, which allowed civil servants to do business with the same government they worked for when that would give them unfair advantage over ordinary people.

FLATTERY

I came face to face with corruption when Mr Moi invited me to State House Nairobi, mainly to recruit me to fight his Vice President Mwai Kibaki.

After the meeting, also attended by senior government officials, Mr Moi made an attempt to compromise me but I declined.

The President was not only good at buying loyalty, he also loved flattery. Once I attended a public rally in Kericho, which Mr Moi addressed.

Upon return to State House Nakuru, some sycophants started telling him how his body – like that of Jesus Christ – had radiated rays of light when he was on the podium.

Rather than admonish them, Mr Moi laughed his head off, seeming to believe the lie.

We cannot discuss Mr Moi without looking at the philosophy of Nyayoism, which shaped his presidency.

KALENJIN

Nyayoism literally meant his governance style would mimic President Kenyatta’s.

Mr Moi believed that Mr Kenyatta had taken Kenya for a personal fiefdom where no line was drawn between public and personal money.

Similarly, Mr Moi wanted to govern Kenya without drawing a line between his and State money.

Strangely, when the Kikuyu elite heard Mr Moi would govern like Mr Kenyatta they believed he would continue to serve their interests.

It hardly occurred to them Mr Moi would only benefit the Kalenjin elite.

The Kikuyu elite’s presumption Mr Moi would favour them while in power benefited Mr Moi, whose government they were willing to tolerate and exploit.

Nyayoism also meant Mr Moi would govern Kenya with the same one-party dictatorship that Kenyatta had governed and would suppress the same democratic freedoms and rights that Kenyatta had.

Mr Moi would also continue to detain without trial, jail and force into exile critics and opponents of his regime, the same way Mr Kenyatta did.