The real scandal in the Tokyo land case and why it is time to abolish EACC

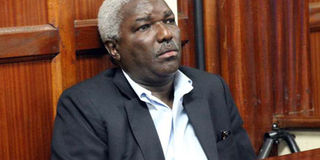

Former Foreign Affairs PS Mwangi Thuita before a Nairobi court on February 22, 2016 for the hearing of a case in which he was charged with corruption. He was charged with corruption in the purchase of the Chancery and Ambassador’s residence for the Kenyan Embassy in Japan. PHOTO | PAUL WAWERU | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- It is too politicised to fight corruption and its addiction to cheap publicity has made it a dangerously unhinged tool for carrying out any serious corruption investigations.

- The EACC and the DPP proceeded on a presumption of guilt. Any evidence that exculpated the accused was ignored.

- The final options boiled down to a straight-forward choice between the rental premises or a 700.39 square metres plot on offer from the Government of Japan.

Since the Kenya Anti-Corruption Authority (KACA) — the forerunner of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) was founded in 1997, all its chairs have been forced out of office; no big fish has ever been convicted on its investigations; each mega-corrupt revelation starts in a blaze of glory and ends in whimper of inaction and, more often than not, its investigations appear compromised, malicious or politically motivated.

When the Constitution is next amended, the EACC should be abolished. It is ineffectual and a drain on the public purse.

It is too politicised to fight corruption and its addiction to cheap publicity has made it a dangerously unhinged tool for carrying out any serious corruption investigations.

If this was ever in doubt its investigation of the Tokyo scandal which has recently ended with a court decision of “no-case to answer” against Mr Mwangi Thuita, former PS, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Mr Allan Mburu, former First Counsellor in Japan, removes it all.

Mr Mwangi and Mr Mburu were charged with corruption in the purchase of the Chancery and Ambassador’s residence for the Kenyan Embassy in Japan.

When I was first asked to review the evidence on which the indictments rested nearly two years ago, it was obvious to me that a great injustice had been done to the accused; that the charges were fatally flawed; without merit in law or fact; that the Director of Public Prosecution, DPP, Mr Keriako Tobiko, had abused the criminal process by agreeing to file the charges on evidence this flimsy and that, eventually, this case was a flagrant and coercive use of the State’s criminal powers.

This two-part analysis of the “Tokyo Scandal” shows exactly what is wrong about the way corruption is fought in Kenya.

The case was built on three shaky foundations: an over-heated investigation by the Parliamentary Committee on Defence, Security and Foreign Affairs headed by Adan Keynan; two rather casual investigatory trips to Japan by the EACC and the report of a Special Audit by the Auditor General.

The accused were said to have committed three corrupt acts: one, conspiring to commit an offence of corruption, namely breach of trust by approving the purchase of the Tokyo property; two, using their office to confer a benefit on the embassy’s former landlord, Mr Nobuo Kuriyama, from whom land and buildings were bought; and three, failing to follow procurement laws.

FLIMSY ACCUSATIONS

Unfortunately, there was no evidence to sustain any of these charges.

The EACC and the DPP proceeded on a presumption of guilt. Any evidence that exculpated the accused was ignored.

The absence of evidence was taken as proof of a conspiracy so deep that all traces of wrong-doing had been erased.

Mr Mwangi and Mr Mburu were said to have personally benefited from the Tokyo transaction yet their financial records showed nothing to support that claim.

This incompetent indictment was built on six claims, some silly ones, some wrong ones and some of which were both silly and wrong.

One, that the accused had recklessly pushed the government into buying the property it had leased since the late 1980s even though better land was on offer from the government of Japan.

Two, that they had paid for the Tokyo property much more than it was worth, principally so as to finagle some kick-backs for themselves.

Three, that they had taken advantage of the Ambassador Dennis Awori’s absence from Tokyo to pull off the scam.

Four, they had exposed the government to serious financial risk by using a judicial scrivener — a kind of solicitor — rather than a qualified lawyer to do the transaction.

Five, that they paid all of the purchase price in cash, again to make it easier for the vendor to pay them bribes.

Finally, that they deceitfully signed two sales contract for this transaction, in the first Mr Mburu arrogated himself a power of attorney he did not have and in the second Mr Thuita duplicitously tried to cover that up, presumably in order to gain corruptly.

None of the six claims stands scrutiny.

PROPERTY DEMERITS

The first claim had no basis in fact. Not only had four different ambassadors over two decades been trying to buy that very property, the land supposedly on offer from the Government of Japan was too small, too expensive and just plain inappropriate.

Moreover, the property on which the embassy of Kenya in Tokyo sits was modified to Kenya’s specifications in the late 1980s and the lease included an option to purchase, two facts that different ambassadors had used down the years to urge the Treasury to buy it.

By 2003, the Tokyo embassy thought that paying rent had become unsustainable: that year the premises were offered to Kenya for 2.5 billion Japanese yen (about Sh1.6 billion) but by then the government had spent nearly 900 million yen, or a third of the value of the property, on rent.

This is the background against which in January 2009, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs sent an Inspection and Validation Team to Tokyo to look at the property options available.

The Team’s Terms of Reference (TORs) were to evaluate six pre-identified plots, to give recommendations on each and if need be to offer justification for purchase or construction as the case might be.

They were also to allocate sufficient funds for the purpose; negotiate discounts with the government of Japan and fast-track the buying of property.

Among the six properties to be checked out was the plot on which the embassy and chancery sat.

Of the other five, two had already been sold by the time the team got to Tokyo.

Another other two were subject to a highly regulated auction process that had no in-built guarantees that the land would in fact be available.

So the final options boiled down to a straight-forward choice between the rental premises or a 700.39 square metres plot on offer from the Government of Japan.

Unfortunately, the plot on offer had on balance many disadvantages: it was empty and half the size of the land on which the embassy sat.

Moreover, its 1.31 billion Yen price tag seemed too high for empty land: if the Team opted for it, they would also have to factor in the costs of construction as well as the rent that Kenya would continue to pay during the construction period.

ILLEGAL BENEFIT

The decision to buy the embassy premises — combining a built up chancery and residence — eventually proved a no-brainer.

One claim that got much play in the local media was Adan Keynan’s hyperbolic statement that the Kenyan embassy in Tokyo was located in the equivalent of Githurai.

But as a note verbale — a diplomatic communication — from the Government of Japan pointed out in rebuttal, Meguro Ward - where the Embassy of Kenya is located - also hosted - as of March 2010 - embassies from Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Djibouti, Egypt, Gabon, Kazakhstan, Cyprus, Nepal, Poland, Senegal, Sudan, Uzbekistan and Papua New Guinea.

Was it over-priced? The EACC and the DPP said that it was: a claim that was based on a valuation by a company called Coral Corporation and another by the Government Valuer, Teresia Kimondiu.

Let us begin with the Coral Corporation valuation. According to this valuation, Kenya lost Sh700 million.

This was the difference between the sale price and Coral Corporation’s valuation.

Inexplicably though, the Corporation had valued only 1,195.33 square metres of the property — without the buildings — instead of the whole plot which measured 1,435 square metres with the buildings.

It turned out that the government had no basis to rely on the Coral Corporation valuation: the company’s agent, Mr Hidehiko Takahashi, admitted in a written statement to the Japanese Judicial Police on October 17, 2011 that he was “not a real estate appraiser” — that is, a valuer — and that, therefore, he did not have authority to prepare “real estate appraisal certificates.”

The DPP could have, had he been interested, easily discovered this.

On her part, the Government Valuer Teresia Kimondiu gave a value of 1.43 billion yen against a sale price of 1.75 billion yen.

The prosecution argued that the 318.7 million yen difference between the price and the valuation was was an illegal benefit to the vendor, Mr Nobuo Kuriyama.

UNRELIABLE FIGURE

There are two reasons why the EACC and the DPP are wrong on this.

First, in 2007 this same property had been mortgaged for 1.94 billion yen, a critical point given the fact that mortgages in Japan are usually 80 per cent of the value of the property.

Second, valuation is not the same as price. A valuation provides a guide to negotiation but the price is what a willing buyer and a willing seller agree to given the market conditions.

This point was made clear in 2008 when the government sold consular property in Lagos.

There were two valuations there: a government valuation by the very Teresia W. Kimondiu and a valuation by a private Nigerian valuer.

Kimondiu valued the Lagos property at Ksh 391,430,000 whilst the private valuer put it at Ksh 428,996, 252.

The sale price was Ksh 994,205,065, a variation of 154 per cent between the official valuation and the eventual price.

But there were special difficulties in the way Ms Kimondiu valued the Tokyo property that makes her figure totally unreliable as a basis for a criminal charge.

She gave a value of 1.43 billion but, as in the Coral Corporation valuation, this was the value of the land only.

She gave a separate value for buildings, 149,318,200 million yen, which she excluded from the total value of the property on the mistaken view buildings as old as these ones were obsolescent.

In fact as a Government of Japan note verbale to the Kenya government pointed out, buildings in the country have a much longer life-span.

The obsolescence rule was tax purposes only. Had the value of the buildings been included in Kimondiu’s figure, the value would have been 1.58 billion Yen, making a variation of only 9.7 percent between valuation and price.

Wachira Maina, a constitutional lawyer, reviewed the evidence files for the defence in this case.