Admission figures point to serious crisis in universities

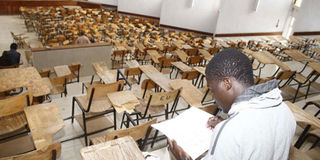

A student in a near-empty lecture hall at Egerton University in Njoro, Nakuru County, on March 19, 2018. The university's teaching staff have been on strike for the better part of 2018 as they demand the implementation of their 2017-2021 collective bargaining agreement. PHOTO | AYUB MUIYURO | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

The country has 74 universities – 31 public, 16 public constituent colleges, 18 private, five private constituent and 14 with letters of interim authority – but most of them are not sustainable.

At least one private university that has a capacity of 50 did not attract any student at all, while another that can accommodate 400 only got eight. A public university only attracted four students.

In total, universities declared they could admit 132,686 students, however, only 62,851 representing 47.4 per cent of the places were filled.

Details of the crisis facing higher education are now coming to the fore following the release of this year’s admission list. Many universities face bleak future because they cannot attract students hence may not survive if the trend continues. Even those which may survive will have to scrap several courses that have turned out to unpopular and irrelevant.

An analysis of the admission figures, released by Education Cabinet Secretary Amina Mohamed this week, is quite telling. Many private universities as well as newly-established public universities cannot attract students raising questions about their viability in the coming years. Equally dramatic, public universities will no longer offer parallel degree course because of lack students. This is a consequence of remarkably reduced number of qualifiers following stringent rules introduced two years ago to curb examination cheating in high schools.

Only 69,151 candidates obtained grades C+ and above in last year’s Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) examinations, which is the threshold for university admission. And with the tight controls instituted by the Commission of University Education (CUE), the bridging courses that offered alternative pathway for non-qualifiers to join universities, have since been scrapped.

In total, universities declared they could admit 132,686 students, however, only 62,851 representing 47.4 per cent of the places were filled. This means that more than half of the capacity – 52.6 per cent – of the universities will be unutilised.

The country has 74 universities – 31, public universities, 16 public constituent colleges, 18 private chartered, five private constituent colleges and 14 with letters of interim authority – but most of them are not sustainable. What is emerging is that university education was built on quick sand. The exponential growth witnessed in the past 20 years was a mirage. It was not based on fundamentals. Now the chips are falling in place and the reality is that the country may not require so many universities after all. Countries like South Africa and Rwanda have had to confront with such reality in recent years and made the painful decision of collapsing and reducing the number of their universities.

This is the new reality emerging from the latest admission report just released by the Kenya Universities and Colleges Central Placement Service (KUCCPS). However, the admission figures cover 65 universities that declared their capacity. Some private universities such as Strathmore and United States International University-Africa, generally popular because of quality programmes, do not admit through KUCCPS as they have their own systems.

According to the list of admission, at least one private university that has a capacity of 50 did not attract any student at all, while another that can accommodate 400 only got eight. Similarly, one public university only attracted four students. In total, 14 universities got less than 50 students each, figures that cannot sustain an institution.

Public universities will have to drop parallel degree programmes - module II - that thrived in the past two decades and turned out to be major revenue earners that sustained the institutions at a time when government slashed funding drastically and left the institutions to more or less fend for themselves.

Looking at the admission data, it emerges that several courses failed to attract takers. These include agriculture, horticulture, dairy production, food science and technology, wildlife and natural resource management, environmental studies, and marine studies.

Others in the humanities are psychology, conflict management, community and general arts subjects such as geography. It is not lost that most of these courses were introduced at the peak of explosion of student admission, when demand soared and universities resorted to starting so many programmes to get numbers.

Some courses were excised from existing broader programmes, which amounted to cannibalisation, while others were exactly duplicated and clothed in new glamorous names. Now, the chickens have come home to roost. It has come to pass that these courses do not really add value, among others, because of dim prospects for jobs and also shallowness in preparing students for professional practice of further education.

The admission figures have serious implications on higher education. First, do we need the number of universities and courses? Why do the universities that started off as niche institutions, such as Egerton (agriculture), Moi (science and technology) or Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (agriculture and technology) but veered off to humanities continue offering them yet they do not attract students? Isn’t there merit in collapsing some of the courses to provide compact programmes that adequately prepare students better for jobs and further education?

And all these relate to university financing; why should the government continuing sharing out little cash it has to several universities that operate below capacity?

Take the University of Nairobi, the country’s pioneer institution of higher education, which has some three courses that are more or less the same but segmented into different entities yet none can attract good number of students.

Tied to this is legislation. CUE is obliged to provide for the establishment of a university in each county. In this regard, the revised Universities Act 2014 requires the commission to give an update on the status of established universities in the counties every year. The result is the creation of Bomet University in Bomet County, but which has only attracted 21 students, Alupe University College in Busia, which only got 79 students and Turkana University in Turkana County, four students. Clearly, these are unviable ventures.