Why many insist on staying in office at the peril of public interest

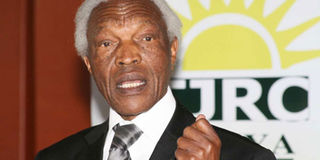

Former chairperson of Truth Justice and Reconciliation Commission Bethuel Kiplagat at a pat event. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- In November 2010, the late Ambassador Bethuel Kiplagat stepped aside as the chairman of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission.

- When I asked Kiplagat about his insistence on returning to chair the TJRC in August 2011, his answer was simple: “to show that I’m innocent”.

- The real reason that people insist on remaining in office despite widespread opposition is complex and varied, with some more concerned about the loss of status and salaries, and others with the possibility of future sanctions.

Following the Supreme Court’s ruling that the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) had not conducted the presidential election of August 8, 2017 in accordance with the Constitution and applicable laws, and that a fresh election be held, many have called for key IEBC figures to stand down or be replaced.

Some have also called for the prosecution of specific individuals.

One of the things that is striking as a non-Kenyan is that key figures in the IEBC have not already stood down. Not because they are necessarily guilty of purposefully undermining the electoral process — I do not know whether they are guilty of such offences or not — but because, at the very least, they oversaw a flawed process and should accept that their position is now an obstacle to public confidence.

Critically, this points to a bigger problem; namely, a common refusal of public figures to stand down even when their position has become the subject of a crisis of confidence.

STEP ASIDE

To give just one example, in November 2010, the late Ambassador Bethuel Kiplagat stepped aside as the chairman of the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC).

However, he refused to step down and returned to chair the commission in January 2012. This was despite the fact that opposition to his position clearly undermined the TJRC’s work and diverted attention from the commission’s public hearings and final report.

At one level, opposition to Kiplagat stemmed from the fact that he had served as a senior civil servant in President Daniel arap Moi’s government.

However, he was also connected to several injustices that the TJRC was tasked to investigate, including the Wagalla massacre of 1984.

In turn, while few believed that Kiplagat was guilty of ordering a massacre, or of other wrongs, many felt that he should not chair the TJRC but instead be summoned to give evidence before it.

But why do public figures such as the late Kiplagat refuse to step down even when their tenacity undermines the very process that they profess to care so much about?

INNOCENT

When I asked Kiplagat about his insistence on returning to chair the TJRC in August 2011, his answer was simple: “to show that I’m innocent”. In his words, if I left, “I would have been negating the very purpose of the TJRC — the truth — and, if I quit like this, then (it would) encourage the TJRC to continue with allegations without the truth”.

Clearly, the real reason that people insist on remaining in office despite widespread opposition is complex and varied, with some more concerned about the loss of status and salaries, and others with the possibility of future sanctions.

However, one common theme is a sense that, somehow, the very act of standing down would be taken as an admission of guilt.

This is different from many countries where standing down is not necessarily perceived as an admission of guilt and is instead often cast as an act in the public interest.

An association of standing down with an admission of guilt is a problem as no one likes to admit wrongdoing. As the sociologist Leigh Payne has shown in her study of perpetrator accounts of past violence, the most common type of account is not remorseful confession, but denial and silence whereby, if “perpetrators admit to their roles in the past”, they “deny wrongdoing or knowledge of wrongdoing”.

REMORSE

As Payne goes on to argue, acknowledgement and remorse are likely only when there is evidence of individual involvement; strong incentives to publicly accept responsibility; and people have had reason to re-evaluate previous justifications for their own actions.

However, such factors are rarely in place. It is often difficult to isolate an individual’s responsibility within a complex system — with a tendency for those in leadership positions to blame those who implement policies and vice versa.

There are also often strong incentives not to accept responsibility, for example, if this might lead to sanctions or implicate powerful people. While many also know that they can rely on the protection of the State and support of co-ethnics.

The fact that many insist on remaining in public office even when this fuels a crisis of public confidence is thus a common problem that deserves public debate and attention.

Gabrielle Lynch is Professor of Comparative Politics, University of Warwick, UK. [email protected]; @GabrielleLynch6