Legend of Tanzanian marathon runner Akhwari: Winning is not everything

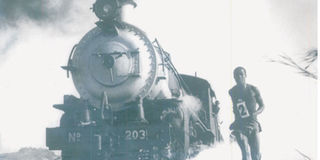

Rhodesia’s Mathias Kanda runs alongside a moving train between Gwelo and Selukwe during training for the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games. Mamo Waldo won the Olympics gold while Tanzanian John Stephen Akhwari finished last, but will be remembered for bravely battling through a bad fall to cross the line bloodied and battered. PHOTO | FILE |

What you need to know:

- Worse for wear, the badly injured runner came in last at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics games, over an hour after all other runners had crossed the finishing. His brave ‘victory’ captured the imagination of the world and his home nation.

- The starting field of the Mexico ’68 marathon featured 75 runners.

- Of these, 18 would drop out as the altitude took its toll.

In the countdown to the sound of the starting gun of the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games, we return to the story of John Stephen Akhwari.

Once long ago, he pushed his body to the farthest limits of human endurance and then gave the world of sports one of its most evocative statements about sacrifice and loyalty. Now is as good a time as ever to re-run his story because in the coming weeks, a man or a woman may yet find themselves in his circumstances and be inspired to rise beyond their pain and expand the boundaries of human possibilities.

Before telling you this story, let me digress a bit. In the run-up to the 1984 Olympics, I read a story of how Ryohei Kanokogi, the famed Japanese judo teacher, wept all night long as he read the biography of Yasuhiro Yamashita, the greatest judoka of all time. I read the story of Akhwari in 2000 and I didn’t weep despite my emotions. Instead, over and over, I read Dennis Brutus’ short poem in his collection, Stubborn Hope, which goes thus:

“Endurance is the ultimate virtue/more, the essential thread on which existence is strung when one is stripped to nothing else/and not to endure is to end in despair.”

In the Tanzania of 1968, as indeed in most of the developing world, athletics training methods were rudimentary and the science would only come in decades later. Nobody in the country then thought of taking advantage of the slopes of Mt Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain, to train the nation’s athletes for the Olympic Games of that year which would take place in the thin air of high Mexico City.

Tanzania sent four athletes to those Games, Akhwari among them. Beyond basic preparations in the coastal capital of Dar es Salaam to augment their natural talent, they took with them only an athlete’s innate drive to excel and the nationalism imbued in them by their country’s founder and president, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere. Akhwari actually hailed from the Kilimanjaro area where he tilled the fields as a peasant farmer and ran the 10,000 metres and the marathon during his spare time. But the heights of Kilimanjaro’s slopes would prove to be of no help to him in Mexico.

The starting field of the Mexico ’68 marathon featured 75 runners. Of these, 18 would drop out as the altitude took its toll. Akhwari, an African marathon champion who routinely posted times in the range of 2hrs 20min and was in the class of the world’s elite, started experiencing difficulties almost as soon as the race started. He suffered muscle cramps and hung at the back of the pack from where he would come across the anguished casualties as they fell by the wayside one by one.

'NARROWED THE GAP'

Despite his discomfort, Akhwari decided to narrow the gap with the leaders. He marginally improved his position only for the catastrophe that would put his name in Olympic lore to occur. Jostling for position, a group of runners were involved in a pile-up. This happened when the group was approaching the 21-kilometre mark of the race. The incident was serious and some of the runners tumbled heavily onto the tarmac.

Akhwari was one of those who suffered this fate and he dislocated his right knee. Blood gashed from the gaping wound. Picking himself up, he realised that his shoulder was also bruised by the hard surface and now an intense pain was assailing him from head to toe. Looking at his desperate condition, medical personnel shadowing the competitors advised him to pull out. But Akhwari refused.

The medics now had to go against their own advice and help him. Perplexed and overwhelmed by his courage, they carefully bandaged his knee and treated his shoulder before allowing him to proceed. Now limping badly, he fell to the back of the field, way far behind the next to last runner, and the distance between them kept increasing.

Mamo Waldo of Ethiopia, ever so comfortable with the Mexico altitude and having no difficulties of any kind, was leading the pack of 57 competitors still in the race. And 2hr:20min:26sec after start, Wolde crossed the finish line a worthy winner and accepted the thunderous cheers of the massive crowd packing the stands of Estadio Olímpico Universitario, oblivious of the superhuman effort taking place far back in the course that he had run.

More than one hour after Wolde’s victory, darkness was falling over the stadium and the last spectators were going home after a memorable day of athletics.

And then an announcement came through the public address system that there was still one runner on his way to the finish. Many spectators returned to the stands and a television crew raced along the marathon course.

And there was Akhwari, limping heavily on his injured knee, barely able to walk but every now and then still attempting to run. Some people winced at his every limp as if it was they who were feeling the excruciating pain in his bones and the exhaustion in his lungs. But all of them broke into the loudest cheer they had ever given a competitor. These cheers carried Akhwari over the finish line.

His time was 3hr: 25min: 27sec – about one hour and five minutes after Wolde. But the race, in the grateful judgment of history, is always remembered as Akhwari’s, not Wolde’s – without taking anything away from Wolde.

The journalists who talked to Akhwari after the race asked him the one question on everybody’s mind: why did he endure such punishing circumstances when retiring would have been so perfectly understandable? That is when he uttered the line immortalised as one of the most memorable in Olympic history.

He said: “My country did not send me 5,000 miles to start the race. They sent me 5,000 miles to finish the race.”

NEVER FORGOTTEN

Tanzania has never forgotten this performance and neither has the world. In 1983, Akhwari was awarded a National Hero Medal of Honour. He was a distinguished guest to the Olympic Games of Sydney in 2000 and a goodwill ambassador to those of Beijing in 2008. He has a charity, the John Stephen Akhwari Athletic Foundation which supports young Tanzanians who aspire to run at the Olympics and other major competitions.

Tanzania, once the source of some of Africa’s best distance runners, has long ceded that ground to Kenya and Ethiopia. But the legend of John Stephen Akhwari goes on and won’t die as long as an Olympic or Commonwealth Games torch burns over any city in the world. The Olympic commentator who was so awestruck by his endurance in that race that he intoned “a voice calls from within to go on, and so he goes on,” spoke as much for that moment as for the future.

****

I covered the 1982 Commonwealth Games in Brisbane for Nation Sport. Brisbane is just next to Gold Coast and I went there several times to have fun during gaps in the work. Let me tell you two stories from that assignment.

First story: The opening ceremonies at the Queen Elizabeth II Stadium (QEII) were the most magnificent I had witnessed in my life. Understandable, of course, because I had not been to a similar event before. The highlight of the programme was a spectacular parachute jump over the city. When the skydivers landed dead in the centre of the pitch, they were given a long round of applause and the clapping went on until they disappeared into the main stadium exit.

Three days later, I read a story in one of the newspapers that the running of the Games was going on with clockwork precision, in part because all the rules were being enforced and no quarter given.

In fact, I read, the skydivers who participated in the opening ceremonies were quickly arrested and whisked away from QEII when it was discovered that they did not have accreditation badges to enter the stadium.

I remember thinking: It is well and proper to obey rules but isn’t that taking it a bit too far?

Second story: The Prime Minister of Australia in 1982 was a gentleman called Malcom Fraser. He was, of course, one of the dignitaries attending the opening ceremonies.

When the programme was over, people started leaving the stadium. From the Press Centre, which was adjacent to the VIP Stand, I walked down the steps towards the main exit.

We mingled with all manner of people, mainly dignitaries. On looking around, I noticed that the person directly in front of me was Fraser. He had his hands in his pockets and was engrossed in a conversation with another man. Fraser was just another person in the crowd and I didn’t see anybody take a particular interest in him.

Outside the stadium, he got into his car and his driver took off. He might as well have jumped into a taxi.

At dinner time that evening and still incredulous at what I had witnessed, I asked Mbogo wa Kamau, the chairman of the then Kenya Olympic Association, how Australia’s Prime Minister could walk around like the next guy seemingly without a care in the world. Isn’t that great, I probed Mbogo, do you think our African leaders can do the same?

This was his answer: “An African president has very many enemies. He needs a lot of security. The way these people live here, the prime minister doesn’t need security. But it’s not advisable for us to try it.” Mbogo was a senior superintendent of police before running the KOA.

I was struck by the certainty in his tone. He spoke as if he was stating scientifically proven facts. And maybe he was; security for our MPs is one of our major national problems. Don’t even mention the president.

ROY GACHUHI is a former Nation Media Group sports reporter [email protected]