Sports will come back bigger, better after Covid-19 havoc

Boxing great Muhammad Ali during a bout in 1974. Ali passed away on June 4, 2016. PHOTO | FILE |

What you need to know:

- Coronavirus is a beast like no other, the polar opposite of everything that sporting culture and practice stands for

- It is unclear as of now what major changes in sport, if any, coronavirus will force into sport but I don’t think there will be anything of note

- It is important to believe that this storm shall pass and that it shall pass in good time

It was written for the superstars of this generation that they would face the fate of Muhammad Ali, who spent the prime years of his career in limbo but still returned to the stage to become The Greatest.

In the case of Ali, boxing authorities across the United States stripped or declined to give him a boxing licence for refusing to be inducted into the US Armed Forces and for almost four years, between the age of 25 and 29, he couldn’t box as his case wound through the corridors of justice all the way up to the Supreme Court.

With today’s stars, it is coronavirus. It has brought all sporting activity, as indeed to pretty much everything else as we used to do it, to a grinding halt across the world.

Ali whiled away the time giving speeches in university campuses and to any other groups of people who cared to listen to him.

Today, it is a different ball game. Few of the options available to Muhammad Ali in the late 1950s are available to our stricken stars, many of who are watching in stunned disbelief as this monster that seemingly came out of the blue consumes their most precious asset: time.

Sportsmen and women work with calendars and timetables. Their objectives are time-specific. Even when strategies are made stretching into years, the daily schedule still comes down to what one is doing at this very minute.

As things stand now, nobody knows when the world will be open for business again. Not one person in the world knows for sure if the Olympic Games of Tokyo will take place next year. And that goes for our own Safari Rally and anything else that has been cancelled or postponed because of the virus.

Coronavirus is a beast like no other, the polar opposite of everything that sporting culture and practice stands for. Its containment calls for apartness. But few other activities in life bring people more intimately together than sport. Competitors and technical staff sweat and breathe into each other and fans pack arenas with a tightness that sometimes can’t allow a flea to pass through.

In training and in competition, sport is about contact. Even in those sports where the competitor works alone, like archery and shooting, the coaching and support staff still come into proximity.

The common wisdom of today is that things will never be the same again. It has now become a truism that long after coronavirus is behind us, our way of life will have changed fundamentally. The way we socialise, the way we do business, and the way we bid farewell to loved ones will all have been changed by our straightened circumstances.

BODY COUNT

But in the context of sport, I think what we shall be dealing with is not a change in culture but in the devastation wrought by the virus. It will be a body count, literally and figuratively, but not a change in how we train and how we compete. For me, it is inconceivable that the clock will not resume from where it stopped.

As all manner of businesses work frenetically to migrate to digital formats, as homes become the ubiquitous new work places and the delivery business grows exponentially, the world’s training fields and gyms will be packed immediately after it is rid of coronavirus.

Posta Rangers players warm up in an empty Afraha Stadium, Nakuru, on March 14, 2020 after their Betway match against Gor Mahia was cancelled.

The stadiums will be full again. Competition will take place exactly as before, with even more vigour I am sure, and coronavirus will become but just another blight in the long course of sporting progress.

There have been others before. How many lives and careers and how many sports businesses it will have destroyed in its wake is the only question.

Digital technology will not affect sport any more than it was already doing before the onset of coronavirus. After all the requisite health precautions have been taken, players will resume contact before frenzied supporters.

In football, playing behind closed doors will resume as it was done before — as punishment for errant clubs, national teams and their supporters, but not for health reasons.

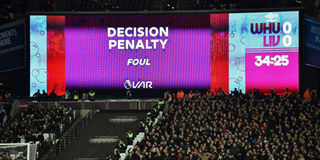

The video assistant referee — an electronic guy I really like and will never understand why he drives some people up the wall — will not mutate into a centre referee, a robot taking charge of a game.

He will remain just that, a mute assistant on the touchline, who does not in any way usurp the authority of the man or woman at the centre of field.

A giant screen shows the VAR decision to award a penalty to Liverpool for West Ham United's French defender Issa Diop's foul on Liverpool's Belgium striker Divock Origi during their English Premier League match at The London Stadium, in east London on January 29, 2020. PHOTO | GLYN KIRK |

In sports history, technology enhances rather than diminishes human participation. Radio greatly popularised football and as it reached millions of people following a single game, bigger and bigger crowds attended the matches in person. The size of stadiums kept on growing, sometimes reaching to mind-boggling figures like 200,000 in a single seating.

Neither did television, even in its colour and later live formats, do anything to diminish spectator numbers. They only went up. Technology whets the appetite of people to come together in sport and never to keep them apart. One of the most hilarious spectacles of the 1960s and 1970s in Kenya was the sight of fans carrying radios into the stadium to listen to the live commentary of the same matches they were watching. It was a double helping.

Every major setback to hit world sport has always produced a corresponding desire to come back bigger, better and more resilient. The Games of all Olympiads ravaged by wars and boycotts were always followed by much more spectacular events, underlining the fact that adversity did not lead in the direction of death but life in abundance.

And throughout time, sports leaders have been torn between striking the right balance between the need to maintain the purity of a sport and adopting to emerging technologies some of which threaten to blur the line between genuine human ability and artificial inputs. As technology has relentlessly marched into the field of play, little has often been said about the robust debates that precede the acceptance of any new normal.

It is unclear as of now what major changes in sport, if any, coronavirus will force into sport but I don’t think there will be anything of note.

The major changes will happen outside the field of play. On this one, the world has changed forever. Many Africans have noted, and not without evident glee even in these tough times, how the virus has hit the mightiest of the earth with great ferocity while it somehow seems to spare them such a dire fate.

Despite dire warnings that the worst is yet to come, many continue to believe that the continent will ride the storm and calm will return sooner rather than later.

This is a deeply religious continent and at least for now, its prayers seem to be holding forth as science is stretched to breaking point elsewhere.

TRAVEL RESTRICTIONS

But things will hit home when the virus comes under control. Restrictions to visit western countries will be so severe as to practically make all Africans persona non grata. Visa applications are stiff enough at the moment and seem designed to strip any African applicant of all dignity. Many people have already decided that putting oneself through such a wringer is not worth the trouble.

The careers of many African sportsmen and women have flourished in the West. These are careers that would otherwise have been stillborn had these young people stayed home. Now the writing is on the wall. Immigration will become difficult tenfold while sports delegations, the eternal itinerants, will find themselves putting up with a whole new slew of bureaucratic requirements.

If it was tough before, it will be in the neighbourhood of impossible in the coming years. Meanwhile, and this is a good thing, coronavirus is a noose tightening around the necks of many African leaders; it is doubtful if any of them will be able to seek medical treatment in their favourite western cities. They will be denied visas and told to have it done at home.

If we are to go by the consensus among the medical community that a vaccine for coronavirus is between one year and one and a half years away, then we must accept that that is indeed a very long way off. This spells doom to so many mature careers and puts promising youngsters in great uncertainty. What will they be training for? Which competitions are their aiming at? Suppose those competitions come a cropper, too. Is there anything other than sport that they can pursue?

Being a young sportsperson in the world today is a difficult space to be in. But the worst thing one can do is to give in to despair. It is important to believe that this storm shall pass and that it shall pass in good time.

A photograph dated May 15, 1975 shows US heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali (front, left) during a training session prior to his bout against England's Richard Dunn in Munich, Germany. PHOTO | ISTVAN BAJZAT | DPA

From the day he won the 1960 Olympics light heavyweight god medal, Muhammad Ali believed he was destined to be the greatest fighter on earth. Yet he was willing to sacrifice his unique gift for a principle: that he had no business going to kill innocent human beings in far-off lands.

It cost him dearly. He didn’t know how long the tortuous road to justice would be. But he kept the faith and in the end, he came out victorious. Coronavirus has imposed itself on humanity and put the careers of some of the greatest sportsmen and women on the line.

No doubt this is very hard on them. What can be harder than to see in slow motion as irrecoverable days of your life pass by? But they should keep going for as long as it takes. They should not be downcast. They should not complain and they should not be bitter. It is the fate they have been dealt. They should embrace it.